Israel’s Precarious Situation

An Israeli political scientist and journalist analyzes the biggest threats he sees Israel facing this year, both foreign and domestic.

Editor’s Note: Throughout this issue we refer to Benjamin Netanyahu as prime minister. As we went to press, Israeli President Reuven Rivlin gave Benny Gantz 30 days to form a coalition government. If Gantz succeeded, he will have replaced Netanyahu as prime minister.

On the night of October 24, 2019, all of Israel’s television news programs led with the same foreboding report: Israel’s strategic predicament had suddenly worsened, and a clash with Iran could come momentarily.

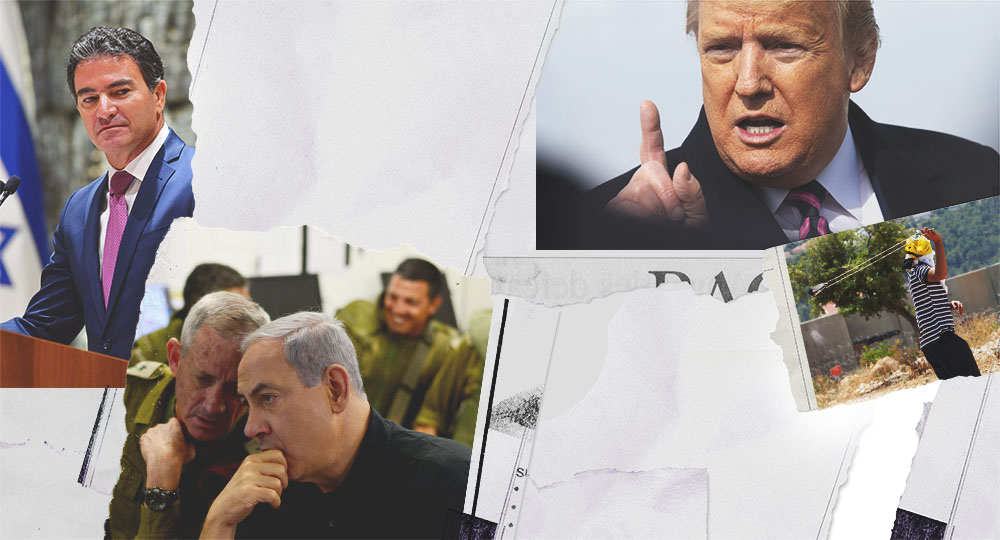

Israelis are used to hearing about the clear and present danger Iran poses. Mossad chief Yossi Cohen had warned us that Tehran was setting up a malevolent “Shiite crescent” across the region. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu emphasized that “Iran is getting stronger,” and its threats to destroy Israel are real. Military analysts repeatedly signaled that a war with Iran or its Hezbollah proxy in Lebanon could erupt at any time and would be devastating for all sides.

What so rattled Israel’s military correspondents on October 24 was what they heard from Israel Defense Forces Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Aviv Kochavi in an off-the-record briefing, the gist of which was that Israel’s strategic calculus had changed.

Foreign Threat: Washington’s Slow But Steady Withdrawal From the Middle East

The tipping point apparently came on October 6 when U.S. President Donald Trump told Turkey’s Islamist President Recep Tayyip Erdogan over the phone that he would pull out U.S. forces that had protected America’s Kurdish allies along the Turkey-Syria border. Afterward, Trump boldly declared that America would no longer “police the world” and is “getting out” of the “blood-stained sand” of the Middle East.

While Jerusalem appreciated the president’s May 2018 withdrawal from the Obama administration’s 2015 Iran nuclear deal, it hoped the move was part of a broader strategy. However, Trump’s apparent intention was to goad Iran into making a better deal; it was not a step toward regime change or even containment.

Trump repeatedly has shied away from confronting Iran militarily: after the June 2019 tanker attacks, after Iran’s not-so-clandestine September 2019 cruise-missile strike on Saudi oil facilities, and after Iran shot down a U.S. drone. The president even flirted with meeting Iranian leaders at the UN in what looked like a replay of his failed approach to North Korea.

To be sure, Trump’s “America First” line is not full-throttle isolationist. He boldly authorized the January 3 targeted killing of Qasem Soleimani, the notorious Iranian general responsible for engineering the “Shiite crescent” across the Mideast. Earlier, Trump ordered the takedown of ISIS chief Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

The United States still has troops in eastern Syria to secure former ISIS oilfields that had bankrolled Syria’s caliphate. Trump also has deployed limited troops in and sent defensive equipment to Saudi Arabia and bolstered forces in Kuwait. Earlier, Washington purportedly launched a cyberattack against Iran’s propaganda capabilities.

Nevertheless, Trump wanted to deliver on his 2016 campaign pledge to end “endless wars.” The day Soleimani was liquidated, the president said the action was intended to “stop a war.” “We did not take action to start a war,” he emphasized.

Next, he threatened Iran if it launched revenge attacks. Trump appears to be signaling that he will do whatever it takes when—but only when—American lives are at risk.

Alliances Forming

The Persian Gulf Arabs and Egyptians assume they cannot rely on the United States to side with them militarily against Persian Iran. In the wake of Soleimani’s demise, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman called Iraq’s pro-Iranian former Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi to de-escalate tensions.

American military reticence also helps explain why oil ministers from Saudi Arabia and Iran not only met in Moscow on October 6, but also left holding hands.

In Yemen, the Saudi-backed regime is now angling to find a negotiated solution with the Iranian-backed Houthi rebels. The national security adviser of the United Arab Emirates discreetly visited Tehran to soothe tensions. Given its rocky relationship with nearby Saudi Arabia, Qatar (though Sunni and Arab) might be the first Gulf state to sign a nonaggression pact with Tehran.

After 9/11, the United States overextended itself under President George W. Bush fighting Islamist forces but not always choosing or conducting its battles wisely. President Barack Obama’s impulse, therefore, was to disengage from the Middle East. Now, say analysts, by explicitly announcing America’s withdrawal in off-the-cuff remarks and impulsive tweets, Trump has created a vacuum that is already being filled by Vladimir Putin’s Russia and, to a lesser extent, China.

Moscow is now the pivotal player in the region’s balance-of-power game, influencing the actions of Turkey, Iran, the Arab states, and even Israel—whose air force must operate in Syrian skies dominated by Russia.

America’s retreat from the world stage also extends to Europe where, in rare bipartisan action, a U.S. Senate committee has moved to make it more difficult for Trump to unilaterally withdraw from NATO.

None of these circumstances is offset by welcome diplomatic moves, such as White House recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital or Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s announcement that the United States does not consider Israeli civilian settlements in the West Bank inconsistent with international law.

America’s departure from world affairs is bad for Israel, according to Dr. Mordechai Kedar, an Arab-affairs expert at Bar-Ilan University near Tel Aviv. The Arab Gulf states and Egypt will have no choice but to accommodate the mullahs, even as Jerusalem remains dependent militarily and diplomatically on Washington, he said.

Netanyahu, floundering politically, has taken this dependency a step further by floating the brash idea of a formal U.S.-Israel defense pact—a step Israel’s defense establishment widely opposes, as does Netanyahu’s political rival, Benny Gantz.

The Drawdown

Meanwhile, Trump has contributed to the distancing of American Jews from the Jewish state. The president’s needling of U.S. Jews for not loving Israel enough and his references to Jews being “brutal killers” in real estate hardly help bridge the gap between the mostly liberal American Jewish community and Israel.

The venerable American Jewish Committee has posted on Twitter, “Much as we appreciate your unwavering support for Israel, surely there must be a better way to appeal to

American Jewish voters, as you just did in Florida, than by money references that feed age-old and ugly stereotypes. Let’s stay off that mine-infested road.”

Paradoxically, if Trump loses the White House on November 3, U.S.–Israel relations are expected to nosedive under a Democratic administration. In harness with dovish U.S. Jewry, Democrats would work to push Israel back to the 1949 armistice lines while ignoring Palestinian-Arab opposition to a national home for the Jewish people anywhere in the Middle East.

Indeed, even Trump’s “deal of the century” peace plan is unlikely to get Palestinian-Arab leaders to recognize the Jewish people’s right to their homeland—though only such recognition would herald a genuine end to the conflict.

Should the next president come from the Democratic Party’s extreme left, the party will probably use Israel as a punching bag while intensifying the use of multilateral diplomacy to cover up Washington’s inexorably waning influence on the world stage.

Either way, America’s clout will continue to recede, no matter who becomes the next president. The United States appears to be a spent force after long wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and it is viscerally splintered at home.

For Israel, America’s slow drawdown from the global stage will necessitate navigating a nasty and brutish world, with its only genuine ally much diminished and its Iranian foe much emboldened.

Domestic Threat: Loss of Binding Ethos Among Jews and Israelis

Like other Western countries, Israel has its share of internal problems, from crime and underpaid teachers to corruption and unequal distribution of resources. Political divisions run deep, as in the United States and Britain. However, the greatest threat facing the Jewish state is corrosive tribalism and the loss of a binding ethos.

In biblical times, this sort of unraveling appeared after King Solomon’s death (c. 933 BC), with the breakup of his kingdom into Judah and Israel; through Israel’s fall (722 BC) and Judah’s fall (586 BC); and later in the lead-up to the destruction of the second Temple in AD 70.

The devastating effects of tribalism have been a motif throughout Jewish history. Still, the ancient Israelite tribes shared a meta-identity. Over the ages, the Jewish people weathered the storms of disunity, fragmentation, and factionalism that buffeted their civilization because they all embraced—whether as sacred history or foundational myth—the Abrahamic Covenant that established the contractual relationship between the God of Israel, the people of Israel, and the land of Israel.

Diaspora vs. Israel

Internal divisions have been a constant backdrop to Jewish life. Jews bickered among themselves, even as they lived at the sufferance of Christian and Muslim civilizations. At the end of the 19th century, the idea of political Zionism divided them—both Orthodox and Reform—even before Theodor Herzl chaired the First Zionist Congress in 1897.

In October 2019 the head of the U.S. Reform movement (the largest stream of Judaism in the United States) tweeted that it would cut ties with the Jewish National Fund to protest Jewish settlement in Israel beyond the 1949 armistice lines. Right-leaning American Jews took umbrage, while in Israel reaction was muted. The thinking was that the Jewish state barely figures in Reform Jewish identity, especially for the younger generations.

When Trump issued an executive order tying anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism, some left-wing Jewish groups objected—just as they did when he cut funds to the corruption-riddled UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, ended assistance to the Palestinian Authority, and recognized Israel’s 52-year-old annexation of the Golan Heights.

One source of the fissure between American Jews and Israel is that outside the Orthodox minority, Jewish literacy in America is declining. Most non-Orthodox Jews would dispute (out of obliviousness and because they find the notion anathema) that the Israel-centric Abrahamic Covenant is the cornerstone of Jewish civilization. Jewish Israelis, however, are far more committed to practicing Judaism than their American coreligionists.

Life in the land is rooted in the Hebrew calendar and seasonal agricultural festivals. Moreover, 57 percent of Israeli Jews light Shabbat candles compared to 23 percent of American Jews, and 64 percent maintain kosher homes compared to 22 percent of Jewish Americans, according to the Jewish People Policy Institute.

The chasm between Diaspora Jews and Israel is worrisome because Israel needs the psychological, political, and financial succor of the Diaspora; yet the divisions inside Israel itself pose the greatest threat to the country’s survival and reflect a vanishing of shared values.

Poverty and Corruption

The insidious peril of Jewish tribalism is not something casual visitors to Israel are likely to notice. They’ll see instead a start-up nation—construction cranes everywhere, roads chockablock with traffic, and a thriving economy—particularly in the high-tech sector.

More critical observers might note poverty, income inequality, violent Arab-on-Arab crime, and lackadaisical attitudes toward worker safety. Traveling around, they would see how Israelis are recklessly inconsiderate drivers, resulting in unconscionably high road fatalities. They would see hospital patients parked in corridors awaiting beds, particularly during the winter flu season, because health services are underfunded.

Political divisions sent Israelis to the polls twice in 2019 with no clear outcome and forced a third national election in March. Corruption eats away at public trust. In the wake of his indictment on bribery charges, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has asked for Knesset legislation to grant him immunity from prosecution. Not coincidentally, his supporters have threatened to give the Knesset the authority to limit the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review. Netanyahu’s Justice and Internal Security ministers have both denounced police, prosecutors, and the courts as biased.

Jonathan Rynhold, of Bar-Ilan University’s Department of Political Studies, says the prime minister has “exploited legitimate debate between conservatives and liberals regarding the role of the Court” to hold onto power at any cost.

However, none of these travails—from political fragmentation and perverted budget priorities to crime and mad driving—is unique to Israel. What is exceptional is that Israel is surrounded by enemies committed to its destruction. So the consequences of the House of Israel being divided against itself is potentially catastrophic.

Bickering Clans and Factions

Bizarrely, Israel is a house divided by design. To enter first grade, Israeli parents register their children in one of four distinct educational systems: secular Zionist, national-religious Zionist, non-Zionist ultra-Orthodox (known as Haredi), and Arab.

For much of Israel’s history, the overwhelming majority of Jewish children attended either the secular state or the national-religious schools. However, the demographic figures have swung in the non-Zionist direction. Nowadays, ultra-Orthodox schools absorb 22 percent of first graders (compared to 9 percent in 1990). Arab children comprise 25 percent. Thus, only a slight majority of first graders attend Zionist schools, either secular (38 percent) or national religious (15 percent).

These numbers portend the demise of the country’s tolerantly liberal Zionist character, warned Israel’s President Reuven Rivlin in a June 2015 jeremiad. He pointed out that the children in the country’s four separate educational systems grow up without interacting, nurtured in totally different environments, and sharing no core values about Israel’s polity. With each tribe going its way, political battles over budgets, resources, and how to share the public square will grow ever more rancorous, with all sides abjuring compromise.

As they enter adulthood, these first graders will cleave to their separate news, cultural, and entertainment outlets. Most will not watch Memorial Day or Independence Day ceremonies on television. “Hatikvah,” Israel’s stirring national anthem, already leaves them unmoved, Rivlin lamented.

“Do we share a common denominator of values with the power to link all these sectors together in the Jewish and democratic State of Israel?” he challenged. Whereas the army once brought at least the Jewish sectors together to help fashion a unified Israeli character, a new majority of young people today, Arabs and Haredim, reject military service—or any other form of national service—which exacerbates tensions with those who do serve.

If anything, Rivlin understated societal divisions because each of these four tribes is internally fragmented into bickering clans and factions.

As Amotz Asa-El, author of The Jewish March of Folly (available only in Hebrew), sees it, the most significant internal threat to Israel comes from Jews who defy the state’s authority. “I detect three types: the far-right, far-left, and ultra-Orthodox. The far-right defied Israeli governance by establishing unauthorized West Bank outposts. The far-left undermined Israeli diplomacy when, for example, it lobbied Brazil to reject the appointment of a settler leader as ambassador to Brasilia; and the ultra-Orthodox undermined the state by ordering its youths to dodge the draft.”

Trying to Bridge the Gap

So, there is no doubt that Israel’s president is correct to bemoan the loss of a shared ethos. He worries over how the Zionist population can connect with the ultra-Orthodox and Arabs who together are on track toward becoming half of Israel’s inhabitants.

The 80-year-old Rivlin, who comes from the same Zionist movement that nurtured the late Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, has made bridging the gap between Israel’s disparate tribes the cornerstone of his presidency. He appeals to them to engage with each other, share in the national burden, and embrace tolerance. He hopes that partnership can mold a shared “Israeliness.”

However, he acknowledges that even these limited goals require semantic, religious, and ideological comprises. Even if miraculously the tribes were willing to cooperate for the greater good, they would still fall short of manifesting the kind of shared ethos Israeli society genuinely needs to survive. But it would be a start.

A brighter future hinges on the emergence of an Israeli leadership that appreciates the absolute need to give competing tribes sufficient incentive to pull together. This would, of course, require Israel’s paramount elected officials to abjure the temptation of demagoguery and populism of playing one tribe against the other. So far, there is little sign of that.