A City Divided

On June 30, 1967, the first Friday after the official reunification of Jerusalem, Muslim and Christian Arabs—whom Jordan had banned from the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque, and Church of the Holy Selpulchre, respectively—worshiped freely in the Old City for the first time in 19 years.

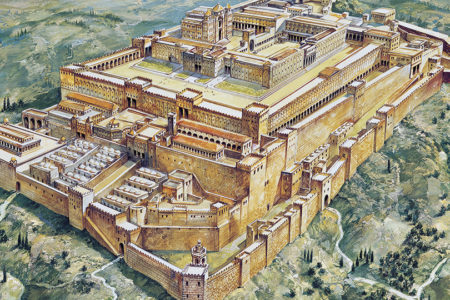

Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of Israeli Jews converged on the Western Wall in the biggest pilgrimage since the destruction of the second Temple in AD 70.

Gone, wrote historian Sir Martin Gilbert, were the “STOP! DANGER! FRONTIER AHEAD!” notices. Gone, too, were the 15-foot walls, barbed wire, and mines that had blocked off streets.

It has been 47 years since the reunification. Memories of life in the divided city (from the War of Independence in 1948 to the 1967 Six-Day War) seem to have faded. But as some world leaders talk about dividing the city again, it’s good to look back and remember what life was like in those days.

The armistice between Israel and Jordan, signed on April 3, 1949, did not constitute a political end to the conflict or an agreement about borders. It left the city in limbo. Still, it didn’t stop people from trying to carve out a sense of normalcy.

As a result of the fighting, the Jewish population in Jerusalem dropped to 69,000. Many people left for opportunities in Tel Aviv. Fewer than 1,000 Christians and virtually no Muslims remained.

Since Jerusalem was the epicenter of Zionism, it was only fitting that in August 1949, the remains of Binyamin Ze’ev (Theodor) Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism, were reinterred there at the military cemetery now bearing his name. Herzl, who died in 1904 at age 44, had been buried in Vienna, Austria.

For ordinary Jerusalemites, life in the divided city was both thrilling and hardscrabble.

Before ushering in the Sabbath on February 11, 1949, Moshe Sachs dashed off a letter to his parents in the States. He thanked them “loads!” for their latest package: canned milk, chicken, baby food, and bars of soap.

Sachs, a Conservative rabbi, had come to Jerusalem after serving in the U.S. Army during World War II. He wound up in the Haganah, the prestate Jewish underground headed by Jewish Agency leader and Israel’s first premier, David Ben-Gurion.

Though he worked for the Agency, Sachs’ salary didn’t cover such “luxuries” as a stove, refrigerator, or washing machine. His letters home show how appreciative he was of the generosity of his parents who, bit by bit, shipped the appliances from the United States.

In a letter dated March 29, 1949, he wrote,

Last Shabbat, we took a long walk through Julian’s Way [today King David Street]. It was the first time I’d been right in front of the King David hotel and the Jerusalem YMCA. The area had been secured in the fighting immediately after May 15, but civilians had been kept out until recent weeks. Now the area is again humming—with immigrants and families that are spreading out.

Water supplies were erratic. By being thrifty and drawing water from a cistern under the porch, the Sachs family had enough to meet most of its needs.

Electricity was so dear that the family used kerosene for cooking and heating. People would line up to buy kerosene sold from the back of a truck. However, there was one job where they didn’t skimp on electricity: laundering the diapers in the washing machine.

There was no money for furniture. So the Sachs family ate off boxes and suitcases—and still entertained regularly.

Telephones were a luxury. Few people had one. Moshe’s father in the United States had a heart attack, so Moshe tried to keep up to date by relying on ham radio operators.

There were not many stay-at-home moms in Jerusalem in those days. Women worked to help make ends meet. Workers could never count on getting paid on time. Fortunately, corner grocery stores and butcher shops operated on credit for months on end.

Yet the atmosphere was far from glum. As conveyed in Sir Martin Gilbert’s Jerusalem in the Twentieth Century, here is how Benjamin Ferencz, a Hungarian-born American lawyer and former prosecutor at the Nuremberg, Germany war-crimes trials, found Jerusalem in 1950:

Everyone seemed so full of hope and enthusiasm . . . that a new era was dawning for them. And the children were all so beautiful and the source of so much pride to all and not merely to the parents. The Jews I knew back home were all lawyers, doctors or businessmen, and here I saw workers in the streets, cleaning and digging ditches.

Gilbert also recounted the experiences of Mary Clawson, a Californian whose husband was an adviser to the Israeli government. She captured the city’s ambiance in a 1953 letter home:

Almost everyone looked poor; I did not see a single woman wearing hose, and the men wore no neckties; I must say I think the lack of hose and neckties were both excellent ideas. There seemed to be an astounding number of good bookstores around.

We have no ration cards yet. So no coffee, eggs, meat, margarine, sugar, soap, etc. The neighbors have been unbelievably helpful and friendly and given or loaned us precious rationed things to eke out our meals, though I have been eating a huge amount of plentiful bread. I have never met so many people I like in so brief a time.

Food was indeed a problem for the entire country.

About half the city’s food supply needed to be trucked to the capital over rudimentary roads. And, as Mary Clawson wrote, “The food budget needs constant watching and scrimping, and no dining out.” She also said there was “no money for a car” and “not enough money for clothes.”

Life in the Arab sector of divided Jerusalem was even harsher. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan made little constructive investment in the city. Its main feats involved demolishing the Jewish Quarter and dozens of synagogues in the Old City, desecrating Jewish graves on the Mount of Olives, and formally annexing east Jerusalem in December 1948.

On July 27, 1953, Jordan’s King Hussein announced Jerusalem would be his “alternative capital,” though he remained in Amman most of the time.

Israelis responded to Arab rejectionism and intimidation by building the area of Jerusalem they did control.

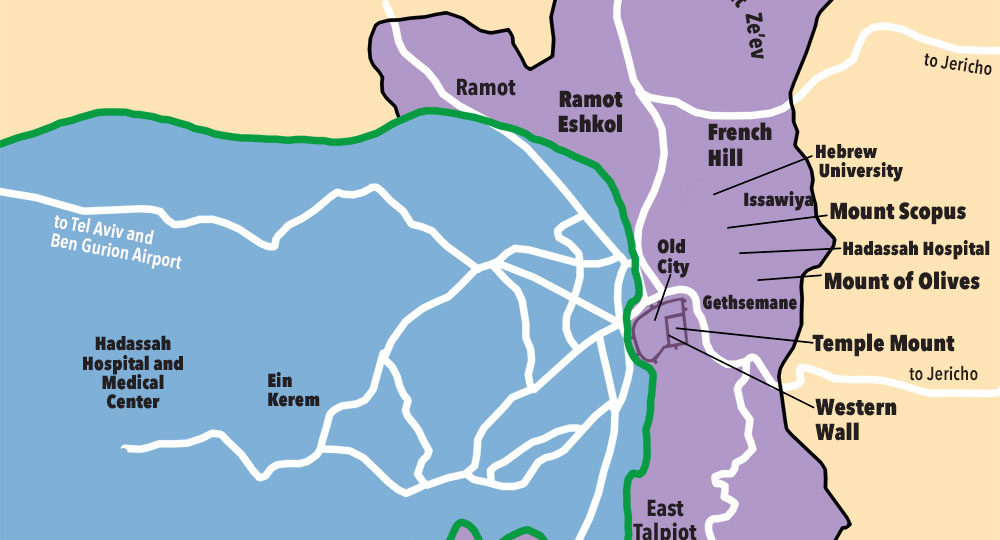

Unable to use its historic Mount Scopus campus because it was encircled by Jordanian-controlled territory, Hebrew University made the Terra Sancta compound in central Jerusalem its main site and held classes at dozens of locations around the city. In 1958, the new Hebrew University campus in Givat Ram was inaugurated.

Hadassah Hospital on Mount Scopus was similarly off limits. So a new hospital was constructed on the hills overlooking Ein Kerem and opened in 1961. The hospital became a reality thanks to the generosity of thousands of American-Jewish “Hadassah ladies” who helped raise the funds for its construction. Hadassah is the world’s largest women’s Zionist organization.

The Binyanei Ha’uma (People’s Congress) convention center, begun in 1950, was fully completed in 1963. Ben Yehuda Street became the heart of the business district, and nearby Mahane Yehuda Market continued to thrive as the city’s fresh-produce market.

Tourism became an important element in the city’s economy, and new hotels went up.

Some tourists passed through west Jerusalem on their way to the Arab side. In 1958, Rev. John Keppel; his wife, Mildred; and their two children, Daniel and Mark, flew to Lod Airport outside Tel Aviv via Athens. Rev. Keppel was on his way to his new congregation in Indianapolis, Indiana, after three years of missionary work in Falkirk, Scotland.

Dan was about 10 at the time. The Keppels crossed into the Jordanian side of Jerusalem through the Mandelbaum Gate checkpoint. From there they toured the Old City, Jordan River, and Dead Sea before heading to visit an orphanage in Jordanian-held Bethlehem.

Dan, now a financial consultant in New Jersey, showed me some of the slides his parents took of the visit. One is a forlorn photograph of the Western Wall.

On the Jewish side of town, journalist Gershon Agron, founder of the English-language Palestine Post—later The Jerusalem Post—became mayor in 1955. Even as mayor, Agron insisted on reviewing the Post’s daily editorial before the newspaper went to press.

All the while, the menace of Arab snipers and infiltrators was never far away.

Jerusalem was surrounded on the north, east, and south by enemy territory. A narrow, makeshift corridor to the west connected the city to Tel Aviv and the coastal plain.

Refugee camps known as ma’abarot housed Jews from Morocco, Libya, Iraq, and Yemen who had come to Israel with practically nothing. In Jerusalem, the camps were often situated just within the Israeli side of the armistice line, along Hebron Road in the outlying Talpiot neighborhood and other places. These areas usually took the brunt of random Arab violence.

Snipers took up positions at Arab Abu Tor and fired at Jewish Abu Tor and on the Jordanian-held Old City walls. Arabs also directed their fire at Kibbutz Ramat Rachel, situated east of Talpiot on the southern edge of Jerusalem’s armistice line, overlooking Bethlehem.

In 1956, for instance, Arab marksmen killed four people attending an archaeological conference at Ramat Rachel, including dentist Rudolph Rudberg, who came to British-held Palestine in 1938 from Germany and was president of the Israel Dental Association.

Arab infiltrators often crossed from the Jordanian-held territories to rape and kill Israelis. Many victims were children and teenagers.

And still, the Jewish people kept building. The Van Leer Institute, a combination of think tank and foundation, was established in 1959. Nearby, the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities opened up shop in 1961. The Beit Ha’am cultural center went up and served as the improvised venue for the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in 1961.

The Israel Museum, home of the Shrine of the Book that houses the Dead Sea Scrolls, was established in 1965 thanks to a grant by the Anglo-Jewish Rothschild family. Reform Judaism built a branch of Hebrew Union College overlooking the inaccessible Old City. And the Knesset finally convened in its own building at Givat Ram on August 30, 1966.

The divided city lacked the vibrancy of today’s united Jerusalem. There were few restaurants and little to do at night, but there were sidewalk cafes. The orchestra came to town; so did the theatre. In fact, the cornerstone for the Jerusalem Theatre was laid in 1964. Plans to construct an official residence for the president of Israel went forward.

The legendary Teddy Kollek, who had been Labor Party Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s right-hand man, became mayor in 1965. His City Hall office was a mere 150 yards from the armistice line.

Teddy Kollek was the right man in the right place at the right time. His mayoralty saw the reunification of the city. His tenure spanned 28 years, and he helped build many of the amenities that we Jerusalemites take for granted in a city that is history-rich but cash-poor.

Kollek had a knack for raising money from abroad. He created the Jerusalem Foundation and identified donors who were as generous as they were wealthy to fund parks, museums, and promenades in the united Jerusalem.

The 1967 Six-Day War in Jerusalem lasted from Monday morning June 5 to Wednesday afternoon June 7. On June 28, the Knesset amended the law of 1950, which proclaimed Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, to reflect the newly defined municipal boundaries. Nevertheless, from that Wednesday afternoon when the Israel Defense Forces recaptured the Old City, there have been those who have begrudged the Jews their unified Jerusalem.

During the 2014 summer disturbances, Arab rioters targeted the state-of-the-art light-rail station and line in the Shuafat Arab neighborhood in north Jerusalem. Though Arabs have benefited greatly from the service, it symbolizes the city’s unity and, moreover, the possibility of Jewish-Arab coexistence under Jewish sovereignty.