A Reminder to Remember

It has been said, “We are what we remember,” and “What we remember affects who we are and what we experience in life.”1 This is especially true of our spiritual lives because what we remember about God forms the foundation for our faith.

In the Torah (Genesis through Deuteronomy), God repeatedly commands His people to “remember” in order to obey Him (Ex. 13:3; 20:8; Dt. 5:15; 8:2, 18; 9:7; 16:12; 32:7). Deuteronomy 6:4–5 gave Israel a brief statement of faith, one Jesus called “the first [foremost] of all the commandments” (Mk. 12:29) and one known to every Jewish person as the Shema.

Deuteronomy 6:7–9 tells the Israelites to remember by making the Scriptures the focus of their lives, instructing them, “You shall write them on the doorposts [Hebrew, mezuzot; plural of mezuzah] of your house and on your gates” (v. 9).

Although this mezuzah commandment may have been a metaphor for spiritual application (cf. Prov. 6:21), it became a literal observance. The word mezuzah first appears in Scripture regarding the doorpost where the blood of the Passover lamb was applied (Ex. 12:7, 22, 23). This physical demonstration of obedience, visible at the entrance to the home, set the people inside apart as belonging to the Lord. Perhaps this act set the precedent for the family faith commanded in Deuteronomy 6:8–9.

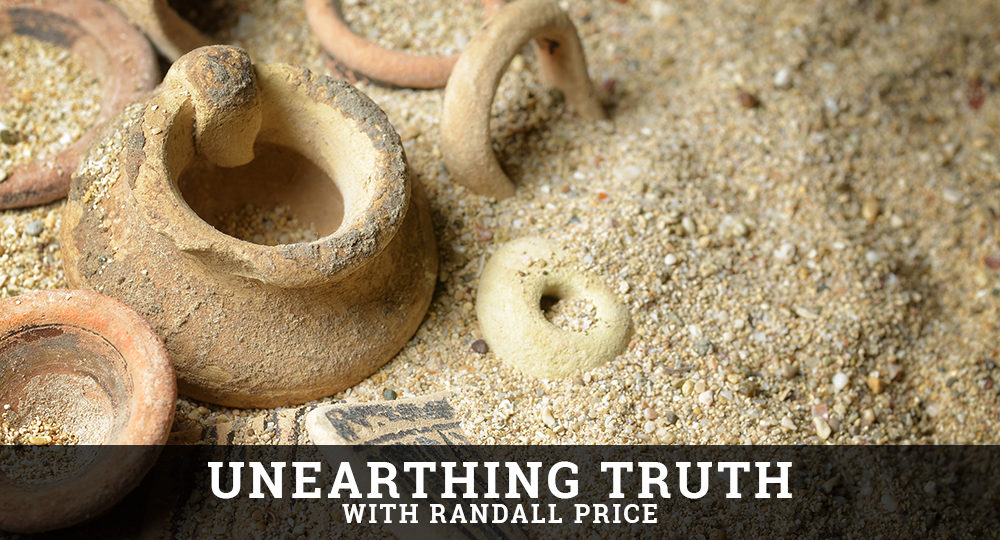

A stone model of a temple from excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa revealed the term mezuzot referred only to recessed door frames of the first Temple;2 but the bronze pillars at the entrance may have had inscriptions, possibly following a literal interpretation of the Deuteronomy command.3

The earliest archaeological evidence for fulfillment of the mezuzah commandment dates from the second Temple period. In Cave 8 at Qumran, a mezuzah was discovered, along with dozens of small leather strips.4 The parchment inside the mezuzah contained the commandments of Deuteronomy 10:12—11:21. The Jewish Targum, an Aramaic paraphrase of the Bible (ca. first century BC), supports the literal interpretation.

Writing just after the end of the second Temple period, the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus noted the mezuzah’s importance:

Let every one commemorate before God the benefits which He bestowed upon them at their deliverance out of the land of Egypt. . . . They are also to inscribe the principle blessings they have received from God upon their doors . . . that God’s readiness to bless them may appear everywhere conspicuous about them.5

Moses Maimonides, famed codifier of the Mishnah, believed the mezuzah had nothing to do with protection but, rather, was meant to help people remember God’s Word:

Whoever . . . has a mezuzah on his entrance, can be assured that he will not sin, because he has many who will remind him. These are the angels, who will prevent him from sinning, as [Psalm 34:7] states: “The angel of God camps around those who fear Him and protects them.”6

Modern Judaism uses the mezuzah somewhat mystically to protect the home. Although the Bible never requires using a box containing Scripture, it does require that our lives be filled with God’s Word. Using a mezuzah or hanging Scripture art in a home may remind us to remember all God has promised and all we have promised God.

ENDNOTES

-

-

- Richard E. Simmons III, “Wisdom for Life, Part 1—Dealing with the Past,” Reliable Truth, podcast (tinyurl.com/2p9satc2).

- Madeleine Mumcuoglu and Yosef Garfinkel, “The Puzzling Doorways of Solomon’s Temple,” Biblical Archaeology Review 41:4 (July/August 2015), 36.

- Franz Landsberger, “The Origin of the Decorated Mezuzah,” Hebrew Union College Annual 31 (1960), 149.

- M. Baillet, J. T. Milik, and R. de Vaux, Les ‘petites grottes’ de Qumrân, Discoveries in the Judean Desert III (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962), 158–61.

- Josephus, Antiquities 4:8.13.

- Maimonides, Mishneh Torah Hilchot Tefillin u-Mezuzah 6:13.

-