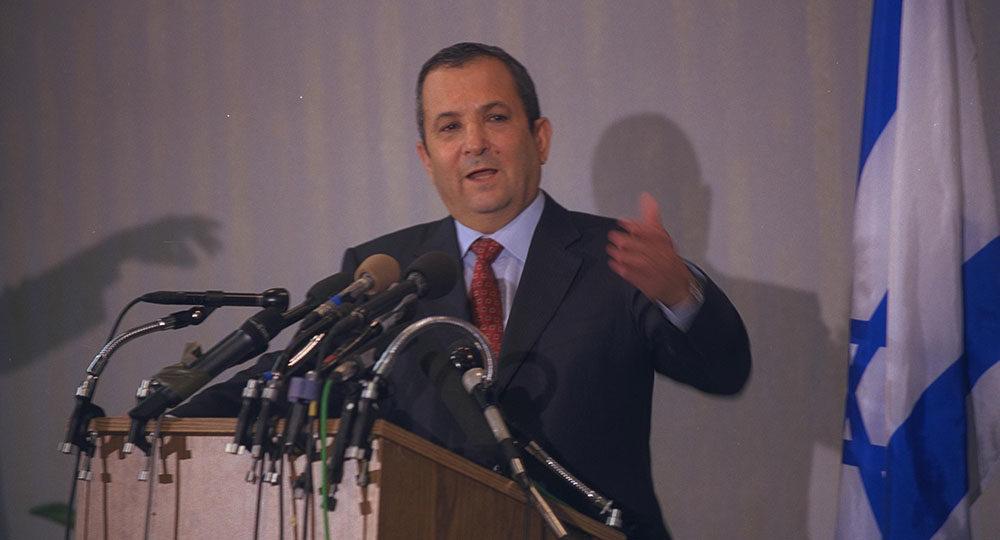

Barak’s Government

Israel’s volatile political scene was struck by lightning the middle of this year with the election of Ehud Barak as prime minister. The One Israel party leader was the choice of nearly six out of every ten voters on May 17. Unlike the late Yitzhak Rabin, the new prime minister was not swept into office on the strength of Israel’s minority Arab voters, although more than 95 percent did choose him. The former general was also picked by a slim majority of Israel’s Jewish voters as 52 percent placed his name in the ballot box.

Barak captured nearly 400,000 more votes than his rival, Likud party leader and incumbent, Benjamin Netanyahu. This big spread surprised most pollsters and political analysts. Surveys had shown him pulling ahead of Netanyahu, but not by such a wide margin.

Analysts said Barak’s strong showing was partly due to the fact that he had earlier changed the name of his Labor party to Israel Echad (One Israel) to cloud its socialist leanings and attract more conservative voters. His official excuse for renaming the party was that it had joined forces with former Likud politician David Levy’s small Gesher (Bridge) party and with the dovish, Orthodox Jewish Meimad movement.

Barak came from behind to win the election. Polls had shown his opponent comfortably ahead in the first months of the campaign. No one disputed that Barak’s lopsided victory was a sharp rebuke for the silver-tongued Netanyahu, who served as prime minister for a short three years. Reeling from his stinging defeat, Netanyahu retired from politics altogether after resigning on election night as Likud party leader. Still, the telegenic, American-educated politician vowed that one day he would return.

The election campaign was strewn with scathing personal attacks between the two main contenders. Netanyahu repeatedly charged that Barak was soft on vital security issues. The Labor leader countered that Israel was close to ruin because of Netanyahu’s alleged mismanagement of the faltering peace process and the economy. Third party candidate Yitzhak Mordechai joined Barak in mercilessly attacking Netanyahu, which analysts said helped set the stage for the Likud leader’s crushing defeat.

With a slight lisp and a dull media presence, the squat and slightly plump Barak hardly seemed to be living up to his family name, which means “lighting” in Hebrew. However, on election day he streaked across the blue Israeli sky like a bolt out of the clouds. It is too early to tell if his substantial victory was just a flash in the pan, or if it will be followed by the reverberating roar of thunder that lighting usually produces.

Barak’s campaign focused on his legendary military record. Banners hailing him as the “Hero of Israel” were hung along most major roads and highways. His television ads bemoaned the gaping divisions in Israeli society—right versus left, secular against religious, Ashkenazi versus Sephardi, etc. He pledged to heal those wounds and make Israel “one nation” again. Indeed, his One Israel party label played off his first name—Ehud—which comes from the Hebrew word echad, meaning “oneness” or “unity.”

Many voters said they had voted not so much for Barak, but against the increasingly disliked Netanyahu. Widely perceived as arrogant and untruthful, the 49-year-old conservative politician was a marked contrast to the unpretentious former armed forces Chief of Staff. Many secular Israelis resented Netanyahu’s perceived pandering to the powerful Orthodox establishment and especially disliked his close ties to convicted Shas party leader Aryeh Deri. In the end, many traditional Likud voters also forsook the leader who had already been deserted by prominent Likud figures such as former Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir and Benny Begin.

Barak was also the choice of many Messianic believers who had overwhelmingly supported Netanyahu in 1996. Like the wider public, Jewish believers were generally unhappy with Netanyahu’s tendency to promise one thing but do another.

The defeated prime minister’s party fared not much better than its fallen leader, shrinking to an astonishing nineteen seats in the 120-member Knesset. This was a dramatic decline from the thirty- two men and women who constituted the Likud block in the last parliament, when the ruling party was united with Levy’s Gesher faction and with Rafael Eitan’s Tzomet party. With less than one-sixth of the current Knesset seats, it is hard to imagine how the despondent Likud will ever recover enough strength to return to power.

However, the Likud was not alone in its anguish. Despite his personal electoral triumph, Ehud Barak’s coattails did not extend to his own party. One Israel captured a mere twenty-six seats in the Knesset, leaving many expectant Labor politicians out in the cold. For the first time in Israel’s modern history, the two big parties failed to capture a majority of the 120 seats. Indeed, they secured only forty-five representatives between them, leading to predictions that the fragmented parliament—containing a record fifteen parties, up from eleven in the previous Knesset—will function only with great difficulty.

One Israel’s poor showing guaranteed Barak’s need to draft quite a few parties into his coalition in order to reach the magic number of sixty-one necessary to form a viable majority government. Coalition bargaining began almost immediately with those parties that openly supported Barak in the race.

After six weeks of intensive haggling, Ehud Barak finally announced his new government in early July. The coalition was not far from the across-the-board alliance he initially sought. It numbers seventy-five seats, giving the new leader a solid base in the Knesset.

Joining Barak’s One Israel party are: the ultradovish party Meretz, the Sephardic Torah Guardians Party (better known as Shas), the Center Party, Yisrael b’Aliya, the National Religious Party (NRP), and United Torah Judaism. The outgoing Likud party decided it best to sit in the opposition rather than further compromise its traditional conservative values. United Torah Judaism has declined any cabinet seats in the coalition since Barak will not completely back away from his campaign pledge to draft most Orthodox seminary students into the armed forces.

The most tempting religious ally was the Shas. Appearing on the electoral map for the first time in 1984 with just four Knesset representatives, Shas flabbergasted even itself by securing seventeen seats—nearly double its former ten and just two less than Likud. The immense growth came despite the bribery conviction in March of party leader Deri and partly as a result of Deri’s legal imbroglio. Many Sephardic voters openly sympathized with his vocal contention that the verdict was yet another example of discrimination by the ruling Ashkenazi elite. In the past, such Israelis strongly identified with Menachem Begin’s Likud as the party of opposition. But after two decades of being part of the “establishment,” the Likud has clearly lost its “outsider” appeal.

The decimated Likud was also invited to coalition talks despite clear differences with Labor over the Oslo withdrawal process. Headed by temporary party leader Ariel Sharon, Likud negotiators indicated their willingness to join a Barak-led government, but put forth several conditions. The most important was that settlement construction in Judea, Samaria, and the Gaza Strip not be frozen as demanded by the Palestinians, Meretz, the United States, and other world governments.

Israel’s three Arab parties, which captured ten seats between them, were not happy that none had been invited to join Barak’s rainbow coalition. “We gave Barak the highest percentage of votes of any group in Israel, apart from Labor party members, and then we were totally ignored,” complained new Knesset member Ahmed Tibi, a senior advisor to Yasser Arafat. The Arab parties warned that they will not automatically support Barak, even in the face of expected right-wing revolts.

Barak can count on the support of the Arab parties on most issues, along with Shinui and Am Echad, which stayed out of the government because they were not offered cabinet seats. This lineup is likely to afford Barak overwhelming Knesset support for any future withdrawal accords with the Palestinians and Syria. However, many analysts expect that the NRP will bolt the coalition if and when Barak agrees to the formation of a Palestinian state or a withdrawal from the Golan Heights. Such a move would still leave the government with a comfortable majority unless other parties also revolt.

The necessary inclusion of so many political factions in Barak’s broad coalition government means that only a relatively few members of his own Labor party have secured the highly contested cabinet seats. Their exclusions are expected to remain an extremely sore point during Barak’s tenure in office.

Echoing his slain Labor party predecessor, Yitzhak Rabin, the new prime minister had pledged during the election campaign to retain control over most Jewish communities in Judea and Samaria, apart from a few isolated ones located in or near Arab population centers. However, he had indicated he will order a halt to all expansion in the settlements—apart from natural growth—and in the disputed Har Homa neighborhood in southeast Jerusalem. To help balance out the controversial settlement freeze, Barak indicated he will insist Israel retain a significant part of the Jordan Valley during upcoming final-status talks with the Palestinians.

The victorious Barak vowed on election night that “Israel will never abandon any part of Jerusalem, nor return to the 1967 borders.” The statement prompted Palestinian Authority leaders to condemn his positions on Israel’s capital city and the settlements. “We not only reject Barak’s positions, but we detest them,” said PA official Abdul Rahman. Foreshadowing tough times ahead, the condemnations were echoed by Egyptian and other Arab leaders.

On the emotional issue of Lebanon, Barak repeated his vow to “bring our boys home” by the summer of 2000. How he will successfully accomplish that goal without producing a wanton slaughter of Israel’s faithful South Lebanese allies remains to be seen.

Syria, which occupies most of Lebanon, expressed cautious optimism that the new administration will meet its demand for an Israeli withdrawal from the entire Golan Heights. While failing to confirm that he will agree to completely abandon the strategic plateau, Barak knows full well that he cannot safeguard Israel’s northern border after a withdrawal from Lebanon without first appeasing the brutal Assad regime’s unyielding demand for a total Golan pullout.

Israel’s new leader will need the strength of his ancient biblical namesake (Jud. 4) if he is to successfully lead his beleaguered country into the 21st century. He faces many complex and incendiary issues.

Zion’s Christian supporters can only pray that the God who made an everlasting covenant with the Jewish people through Abraham, and later confirmed it with King David and sealed it in the Messiah, will bestow His grace and mercy upon Ehud Barak and the people of Israel in the turbulent days ahead.