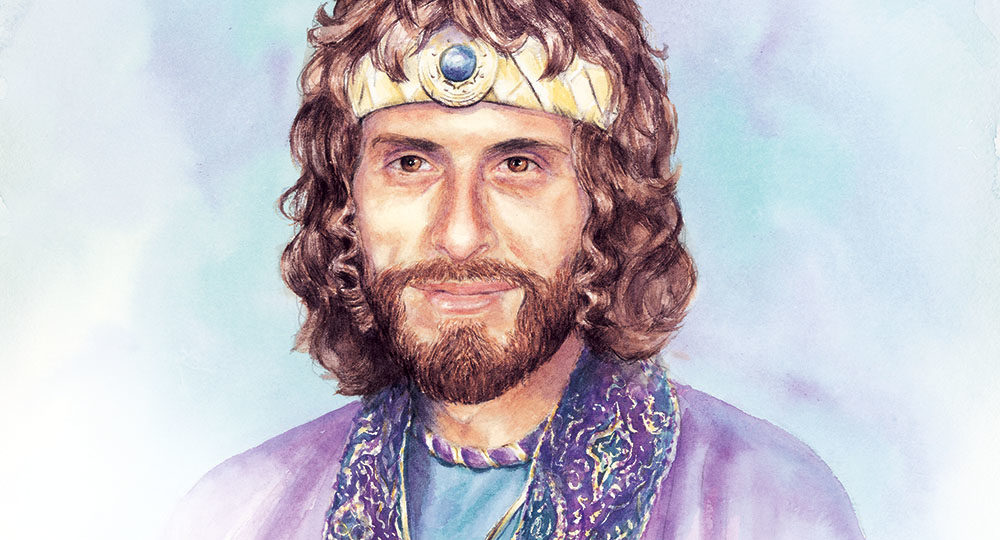

David, Bathsheba, and the Faithfulness of God

For better or for worse, one of the best-known accounts in the Old Testament is that of David and Bathsheba. It is the history of the great king of Israel who, at the height of his power and blessing, committed adultery and murder. Ultimately, however, it is the revelation of God’s faithfulness to His promises: how He dealt with David, a man after His own heart, and how He deals with us.

The Deed

The complexity of David’s sin developed from his attempts to cover it up. Bathsheba was married to Uriah, one of King David’s mighty men, when David committed adultery with her and she became pregnant. His calling Uriah home from battle in order to persuade him to stay with Bathsheba only compounded David’s deceitfulness. When Uriah refused to visit his wife even after David got him drunk, the Hittite turned out to be more honorable than the king (2 Sam. 11:13). (Notice the emphasis on the words the Hittite: vv. 3, 6, 17, 21, 24; 12:9–10.)

So David engineered Uriah’s death at the hands of the Ammonites (11:14–17). After David married the widowed Bathsheba and their son was born, it seemed as if the matter were settled.

But though David was the anointed king, God was the true King of Israel, to whom David was accountable under the Law. The question then became, “What will God do with David, an adulterer and murderer, a man worthy of death?”

The Discipline

Nathan the prophet told David a story about a rich man who took a poor man’s lamb, at which David angrily decreed, “The man who has done this shall surely die!” (12:5).

Nathan then declared, “You are the man!” (v. 7). Confronted with his guilt, David realized he should be executed. But Nathan pronounced the Word of the Lord: “The Lᴏʀᴅ also has put away your sin; you shall not die” (v. 13).

How could this be? Wasn’t Saul rejected from being king because of disobedience (1 Sam. 15:20–31)? David, however, was neither executed nor rejected. Why? Because of the promise the Lord made to him, recorded in 2 Samuel 7, termed the Davidic Covenant. There God promised David a dynasty forever and vowed not to remove the kingship from him or his descendants if they sinned, as He removed it from Saul.

God promised that His loving-kindness (Hebrew, chesed: “loyal covenant love”) would never depart from David. Rather, He would discipline him as a father would a son:

My mercy shall not depart…as I took it from Saul, whom I removed from before you. And your house and your kingdom shall be established forever before you. Your throne shall be established forever (2 Sam. 7:15–16).

As David recounted in Psalm 51:1, he was forgiven because of God’s mercy, love (chesed), and compassion.

God was faithful to His promise concerning the Davidic dynasty, but the consequences of David’s sin were heartbreaking. First, the son born from his illicit relationship with Bathsheba died.

Second, conflict arose in David’s family. Amnon, David’s firstborn and heir to the throne, raped his half-sister, Tamar. Absalom, her brother, avenged Tamar by murdering Amnon (2 Sam. 3:2; 13:1–39).

Third, Absalom turned the Israelites against David and briefly became king before being killed by the commander of David’s army, against David’s wishes. David’s pain on learning of Absalom’s death is a heart-wrenching portrayal of the horrible consequences of sin: “O my son Absalom—my son, my son Absalom—if only I had died in your place! O Absalom my son, my son!” (18:33).

But out of this discipline came hope. After David and Bathsheba’s son died, a second was born to them: Solomon. “Now the Lᴏʀᴅ loved him [Solomon], and He sent word by the hand of Nathan the prophet: So he called his name Jedidiah, because of the Lᴏʀᴅ” (12:24–25). Jedidiah means “beloved of the Lᴏʀᴅ.”

Even as God was disciplining David through his sons, He was also raising up a descendant of David who would be the greatest King of Israel, just as He promised (7:12).

The Depth of God’s Forgiveness

God is faithful to His promises. The history of David and the nation of Israel testifies to God’s faithfulness to His people despite their unfaithfulness. As the apostle Paul said after Christ’s crucifixion, “God has not cast away His people whom He foreknew. For the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable” (Rom. 11:2, 29).

This statement refers not merely to God’s promises to Israel in the Abrahamic Covenant; it also refers to God’s promise to David that his house and “kingdom shall be established for-ever” and that his “throne shall be established forever” (2 Sam. 7:16), which will be fulfilled in the reign of the Lord Jesus Christ. This is the promise we pray in the Lord’s Prayer when we say, “Your kingdom come. Your will be done on earth as it is in heaven” (Mt. 6:10).

The account of David and Bathsheba also has great personal application. Believers in Jesus Christ partake in the New Covenant, which means, as Paul wrote, “There is therefore now no condemnation to those who are in Christ Jesus” (Rom. 8:1). Christ has paid the penalty for sin so that those in Christ by faith are righteous in God’s sight, despite their present sinfulness: “For the wages of sin is death, but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord” (6:23).

But just as the second part of this verse is true concerning eternal life, the first part of this verse is also true: Sin pays out in death. Yet as we saw in David, believers do not receive the punishment they deserve for sin. However, although their sin and guilt are forgiven, the consequences of that sin can be devastating.

Yet after sin, discipline, repentance, and forgiveness, there is restoration. God’s discipline is that of a good Father and is always remedial, not punitive. His grace does not teach that sin is to be taken lightly; rather, it demonstrates the depth of what it means that Christ died for the ungodly—that He died for us.

I am trying to find out if God made this promise to David before he committed the sin against Uriah.

Can you tell me is it yes or no?