Lest We Forget

When invited by the Embassy of Israel to Washington, DC, to attend a prerelease screening of Steven Spielberg’s film Schindler’s List in 1993, I filed into a theater crowded with viewers. Most of them, I presumed, were either elderly Holocaust survivors or Jewish people connected to victims of the Nazi campaign to annihilate European Jewry during World War II.

After everyone was seated, the Israeli ambassador welcomed us. As one of the few Gentiles in the audience, I wanted to assess the film’s accuracy and the reaction to it. Throughout the movie, I could hear the muffled sobs and see in the dim light people shielding their eyes from the brutality being depicted on the screen.

When the film ended, I witnessed something I had never seen before. No one moved or spoke. We sat in silence. Then, still not speaking, we began moving slowly toward the exits, as though we were leaving a temple, rather than a theater.

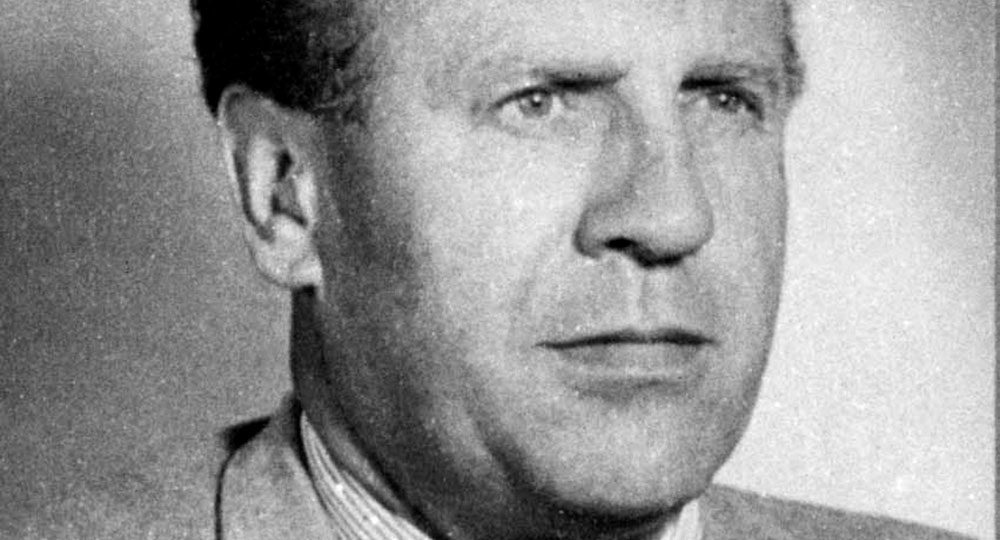

Schindler’s List was based on a well-researched book, Schindler’s Ark, by Australian novelist Thomas Keneally. It told the true story of German industrialist Oskar Schindler, a member of the Nazi Party, who initially dreamed of amassing a fortune by using Nazi prisoners for cheap labor but who ended up a hero instead.

A nominal Roman Catholic, Schindler lived a checkered existence, both before and after the Holocaust. However, for a brief few years he was moved to audacious acts of courage that etched him a well-deserved niche in Jewish history. If we had never heard of Oskar Schindler before the film, by the end of the film we would never forget him.

It seemed we had all been affected. We became aware collectively that there is evil in the world, as well as people of pure wickedness who possess no redeeming seed of goodness within them. Such evil is incapable of being appeased, cajoled, or negotiated into civility. It is implacable and exists in abundance in today’s world.

Ignorance or Indifference?

Many of the Nazis’ victims erroneously believed the Holocaust was a product of Christian animosity and anti-Semitism. After all, Adolf Hitler came from a Catholic family, and many professing Russian and European Christians viewed the Jewish people with hostility.

However, neither Hitler nor the Nazi Party was in any respect Christian. The Führer’s fanatical commitment to himself as a messiah was delusional—yet real and deadly. The Aryan nation’s religion was the “German Church.” Hitler was its “savior”; and Hitler’s rambling manifesto of hate, Mein Kampf, was its Bible.

Exactly how much Western leaders knew of the savage treatment of European Jewry is still a matter of debate. Undeniable, however, are the facts that they did nothing about it and that, with all of the intelligence sources operating inside Europe throughout the war, they knew much more than they were telling.

More complex is the issue of apparent Christian indifference in the West. It is not that Christians did not care; it is, rather, that most of them did not know. Anti-Semitism had pervaded Europe, particularly Eastern Europe. As the war progressed and atrocities became more openly severe, two distinct behavioral patterns emerged. Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, states, “Bystanders were the rule, rescuers were the exception.”1 But there were rescuers, and some of them were Bible-believing Christians.

Most rescuers were ordinary people…from all walks of life; highly educated people as well as illiterate peasants; public figures as well as people from society’s margins; city dwellers and farmers from the remotest corners of Europe; university professors, teachers, physicians, clergy, nuns, diplomats, simple workers, servants, resistance fighters, policemen, peasants, fishermen,…and many more.2

Almost without exception, these rescuers faced a defining moment. It may have come through a knock at the door: a Jewish individual or family pleading for a night’s refuge, or a starving child asking for bread. Sometimes it came after witnessing brutality that could not be ignored. Looking the other way no longer seemed an option.

For most rescuers, their decision was probably instantaneous. Human beings in desperate straits stood before them. There was no time for intellectual discussion. No time for procrastination. The question was simple but life-altering: What am I to do?

The Power of One

For Oskar Schindler, the life-changing, defining moment came as he watched the infamous liquidation of the Kraków Ghetto in Poland between June 1942 and March 1943. Kraków was the location of his enamel factory, where hundreds of Jewish people labored. That was when Schindler stopped being a bystander and became a rescuer. His decision to save Jewish people destined for the gas chambers refocused a life previously characterized by self-indulgence, greed, and a lust for amassing enormous personal wealth.

Thus began the assembly of his famous list that would contain some 1,200 names of Jewish people whom Schindler rescued from death by bribing German officials with money, expensive gifts, and illicit favors. He would be rewarded with three trips to Nazi jails, charged with too much familiarity with Jews; the loss of his fortune by trading it for Jewish lives; and a postwar period of failed business ventures and near poverty.

Schindler’s story of bravery and sacrifice was repeated thousands of times in many different ways for those who dared to exhibit courage in the face of intimidation. Sheltering or helping a Jew in those days was a capital offense for which the rescuer’s entire family paid. Either the Nazis shot the offenders or worked them to death in sweltering or freezing labor camps.

Legacy of Love

Love—the heart-changing, life-altering variety—comes in a great many forms. I have sensed love every time I’ve been privileged to stroll along the carob-tree-shaded Avenue of the Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. In front of the trees are plaques memorializing rescuers honored as Righteous Gentiles from more than 44 countries.

The number of individuals stands at nearly 26,000, of which 11,945 represent those from the Netherlands and Poland. Of course, these numbers do not include the thousands of others who stepped out of the shadows to help and then went, unrecognized, about their lives.

Among those honored from the Netherlands is someone well-known among true Christians: Corrie ten Boom, a courageous woman who in every respect left a true legacy of love. Her plaque reads simply, “Corrie ten Boom & Father Casper & Sister Elisabeth.”

Oskar Schindler’s marker is always bedecked in flowers placed by survivors on his list or their families or by grateful admirers of a man whom they respect for giving up literally everything to save his Jews.

Schindler died in 1974 and is interred in the Catholic cemetery on Mount Zion in Jerusalem. His remains were brought from Germany by a number of “Schindler’s Jews,” honoring his request to be buried in Israel. The spot is a shrine of sorts, as evidenced by the piles of memorial stones placed on and around the marker bearing a cross and the following inscription:

Oskar Schindler

28.4.1908—9.10.1974

Righteous Among the Nations [written in Hebrew]

The Unforgettable Lifesaver of 1200 Persecuted Jews

[written in German ]

It may seem ironic that these rescuers, great and small, who gave up everything, will never be forgotten.In New Jersey alone, 25 streets are named after Oskar Schindler. Yet Adolf Hitler and his Nazi murderers lie unmourned and reviled. No markers. No flowers. No plaques. No memorials.

When faced with compelling circumstances, these righteous Gentiles made personal choices that accomplished what politicians, bystanders, and those who chose to look the other way could not. They stood for what was right in the face of evil, persecution, and death and left a legacy of love that will last forever. God grant us the courage to do likewise.

ENDNOTES

- “The Righteous Among the Nations,” Yad Vashem <yadvashem.org/yv/en/righteous/about.asp>.

- Ibid.