Like a Cat on the Wall

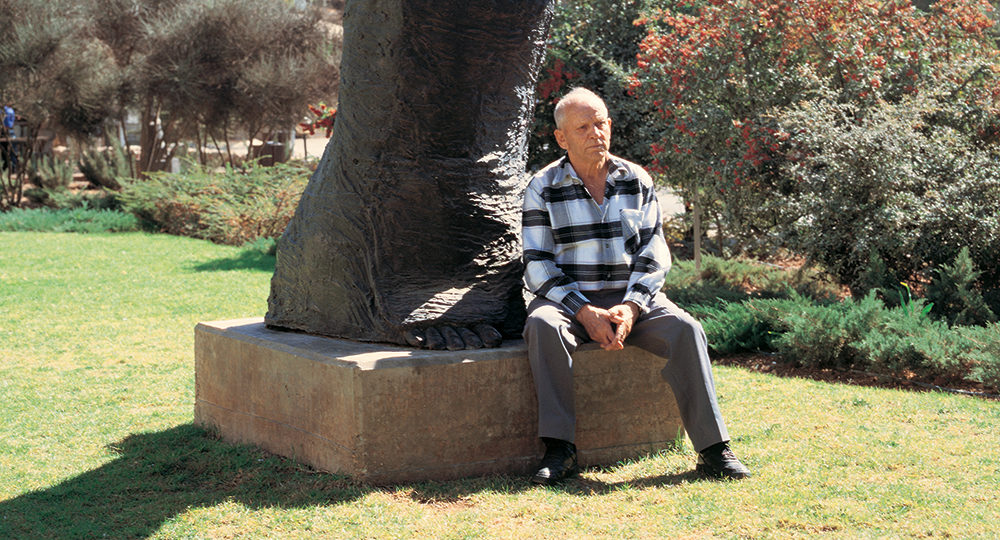

Editor’s Note: For almost 35 years, Israel My Glory readers have eagerly turned to our reports by Zvi, a Jewish believer who has lived in Jerusalem since the end of World War II. He arrived there from Poland, a penniless teenager who had come through the Holocaust completely alone, often running for his life and surviving by his wits and the grace of the God he had not yet come to know.

His spellbinding story has been eloquently told by Elwood McQuaid in the book Zvi: The Miraculous Story of Triumph Over the Holocaust, which was named a 2001 Gold Medallion Book Award finalist.

When Israel My Glory came to life in 1942, Zvi (then named Henryk) was little more than a 10-year-old boy desperately in search of the family he had so deeply loved. Fortunately, his blonde hair and blue eyes concealed his Jewishness; and he carefully obeyed his mother’s parting words: “Do not tell anyone that you are a Jew. My son, you must learn to be strong. From now on you are no longer my child—now you are a man.”

Here is a chapter from Mr. McQuaid’s outstanding book. It is a vivid glance into the life of a Jewish boy whom the Most High God guided through the furnace of affliction and ordained to become a committed, triumphant servant of the Lord.

Darkness was falling by the time Henryk reached the [Warsaw] ghetto. Janusz’s father had been right. Guards wearing heavy military coats that nearly dragged the ground were stationed at frequent intervals along the wall. As he stood pondering the problem of entry, several shadowy forms moved into the alley he had chosen for an observation post. Their approach startled him at first; but as they neared, he could see they were boys his own age. They came abreast of him and stopped. One of the boys, with a sturdy frame and close-cropped hair, asked what he was doing there.

“I am looking for a way to get into the ghetto,” Henryk replied.

“And why do you want to get inside? There is only death and misery beyond that wall.” Henryk responded, “I have come with a message for some friends of my parents. But there are so many guards, it seems impossible to get in.”

“No,” replied the boy confidently, “it is very simple to get in, if one knows how and where to enter. We do it all the time.”

“But with all the soldiers and police, how do you do it?”

“Sometimes we go over the wall at places where there are fewer guards, or those who have little heart to see Jews starved to death. Tonight we will enter through the sewers. You can come along, if you are willing to carry a sack of potatoes on your back.”

This chance meeting was Henryk’s introduction to Warsaw’s famous boy smugglers, who by night dug up potatoes from the fields surrounding the city, then sold them to the Jews confined behind the walls. These children were credited with saving or prolonging the lives of many Jewish people during the days before the Nazis finally destroyed the ghetto. His acquaintance, Peter, was the leader of a band of these Polish lads who were themselves caught up in the quest for self-preservation.

After darkness had cast a thick blanket over the city, the boys took up their sacks and moved toward the entrance of the sewer complex that carried away Warsaw’s refuse. They crept quietly along the streets, just beyond the vision of the men whose business it was to keep the Jews penned up to die.

As the boys descended into the sewer, it was immediately apparent that Peter knew the subterranean passages very well. For Henryk, it was an unpleasant initiation into the smuggling business. The strong stench from the new environment seemed to immobilize his lungs; and for a moment, he drew quick, reluctant breaths. Weighed down by the potatoes, his feet sank deeply into the heavy, wet slime underfoot. Rats loitered nearby. His first impulse was to retreat quickly into the freshness of the night air. But his longing to be reunited with his family overshadowed his revulsion and compelled him to push forward toward his destination.

Finally the boys and their cargo ascended to street level and pushed their way out into the darkness. They emerged inside the Warsaw Ghetto. For a time they sat in the street, drawing deep breaths of nontoxic air. Peter gave orders to his comrades to stay put until he returned. Turning to Henryk, he said, “Follow me and I will show you a place where you can spend the night.” He led him to a niche beneath a porch at the rear of one of the buildings. “I sometimes sleep here myself. It will do for shelter until morning; then you can search for your friends. Good luck!” Peter’s form melted quickly into the murk as he left to go about his business.

Henryk awakened the next morning to find a bright sun penetrating the ghetto. Now he would begin to look for his parents. Striding quickly from between the buildings, he entered the street. The sights that accosted him were beyond belief. Never had he seen so many people in so small an area. Even at this early hour, people seemed to swarm in the street like flies.

Over one-half million Jews had been driven into the Warsaw Ghetto. One hundred fifty thousand of them were refugees who, like Henryk’s parents, had been forced to relocate there. They lived everywhere. Schools, deserted buildings, alleys, and streets all quartered the gaunt, decaying masses.

Starvation and disease reigned supreme. Henryk winced at the sight of emaciated, ragged children with outstretched hands pleading, “I am hungry. Please, give me bread.”

Scattered here and there, close to the buildings, huddled the elderly and the very young, their frail, brittle bodies inching laboriously toward death. Some waited for it silently, while others lifted feeble hands and uttered pitiful entreaties for death to remove them from their horrible existence. Now and then Henryk could hear mumbled prayers for the Messiah to come quickly and bring deliverance.

Scores of those who walked the streets bore the ravages of disease on their faces. According to estimates, as many as 150,000 people in the ghetto suffered with typhus. Tuberculosis, dysentery, and a host of related maladies added to the misery.

Also obvious were the vacant stares of those who had been psychologically scarred beyond recall. Their accumulated suffering and torment had so overloaded their mental sensibilities that they finally went mad. All that remained now were the pathetic physical remnants of once vital people who could do no more than be led about by loved ones or wander aimlessly, waiting for death.

Henryk stood mesmerized by the variegated smells, sights, and sounds assaulting his senses. Suddenly he became aware of a clattering sound coming slowly up the street. He looked around to see a pushcart attended by two men with handkerchiefs over their faces. Human remains lay stacked on the carts like cordwood, as these members of the death crew gathered the bodies of those who had expired during the night. Arms and legs protruded in grotesque gestures amid expressionless faces that stared open-mouthed into the autumn sky. For them, their arduous sojourn in the Warsaw Ghetto was over. Others, however, would live to see the dying continue.

All that day Henryk walked the streets searching faces of passers-by in hopes of finding a familiar figure. Occasionally he paused to inquire about his parents. Some people shook their heads and walked on without so much as a word. One man stopped to listen patiently to the anxious boy. “I have never heard of such a one,” the man said. “Maybe they are all dead, like so many of the others.” His answer did not satisfy Henryk. It couldn’t be, he thought. Not all three of them. That night he retreated to his little haven, discouraged but determined to continue looking until he found them.

It was nearly noon of the following day when he saw a familiar face. It was Mordecai Friedman, a wealthy Jewish man who had lived a few doors from them in the old neighborhood. Determined to catch the man before he became lost in the press of people, the boy ran after his one-time neighbor. The man stopped as the lad called to him. “Mr. Friedman, wait, wait! I must talk to you.”

For a moment the old man’s brow furrowed. Then his face lit up as he recognized his small pursuer. “Henryk, Henryk Weichert. Can it be you? The last I knew of you, you had been sent off to an orphanage. Now you are here in the ghetto. Come, let us sit down on this step. You must tell me how you have come to be in this place.”

The boy and the elderly gentleman sat down together and began to talk of other days. Henryk related his experiences to his friend, who listened with great interest. It was strange that these two, who had barely known each other except by name and face, were now so completely bound together by the thread of the past. It seemed that even recalling the memories of better times was a balm that fleetingly turned minds from their current stresses. When the lad paused, the old man asked about his parents. “Mendel and Ruth, Henryk—are you with them here?”

“No,” the boy replied, “I am searching for them. Can you tell me where they are?”

“I am afraid not,” came the disappointing reply. “They came here at the same time I did, but I have long since lost track of them.”

Henryk asked him if he knew of the address that Janusz’s father had given him. “Yes, I know the place, and I will tell you how to get there.

But you must know that there are now no addresses in this place. Those who lived as one family in a small flat now have ten families living there. It is virtually impossible to find anyone here. If you have good luck, you may run across them. If not, perhaps they are dead.

“Henryk, let me give you some advice before we part. Don’t spend too much time looking for them. You are a boy, and still strong. If you stay here in the ghetto, soon you will grow weak like the rest. Don’t die here. Do everything you can to save yourself.

“And now, my young friend, goodbye. Let us hope the next time we meet will be a better day for both of us.” He thrust out a bony hand and patted Henryk’s shoulder in a parting gesture, then ambled off down the street.

Henryk knew the old man had given him sound advice. Still, he did not feel he could leave until he was certain there was no hope of finding his family. The address he had been given did not lead him to his parents or provide any further clue to their whereabouts. Always the answer was the same: “So many have died; perhaps they are gone too.”

After a few more days of searching, with only starvation rations to eat, the boy began to feel the effects of the lack of food. Friedman’s words came back to him. He must not stay here and die. But he did not wish to give up the search either. After weighing his options, he decided to leave the ghetto and dig some potatoes for himself. He would then set up a business as a smuggler and sell food to the people in the ghetto. It was a dangerous occupation, but no other avenue seemed logically open to him. He would go over the wall that night and hunt for food.

Henryk had little trouble getting out of the ghetto. He was quick and agile—like a cat on the wall.

In addition to stamina and agility, however, this hazardous occupation required either a supreme sense of self-confidence or the drive of sheer desperation. Henryk had a measure of both. He was quite willing to take the chances involved, trusting his wits and agility to get him past the guards and back again. Hunger and the conviction that he must live long enough to see his family stoked the fire that provided the mental impetus to go on.

Once he was out of the city, he had but a short distance to go before he came to a small village. Outside the town lay several fields with potatoes enough to serve his purpose. Henryk burrowed along the rows until he had unearthed a sufficient quantity to fill both his stomach and the sack he carried. Slinging the lumpy load over his shoulder, he made for the city and the ghetto in search of a customer for his first transaction. The next morning it did not take long to find an interested party.

The man was tall and haggard. Several children clustered about him looking hungrily at Henryk’s treasure. “Wait just a moment until I get a box,” the man instructed. Within moments he returned carrying a small container. As the boy began to transfer the precious potatoes to the box, the man and the children began knocking them away. No sooner had they hit the ground than the children scooped them up and thrust them into their ragged pockets; few of them reached their intended destination. The man hefted the box and balanced it for a moment. “It looks like you have about eight pounds here,” he said.

Henryk was livid with anger. “It is more like twenty,” he thundered.

“No, I will pay you for eight pounds of potatoes.”

“But I risked my life to bring them to the ghetto. Now you are trying to steal them from me.”

The man spoke tersely. “If you don’t like it, take them elsewhere.”

His impulse to assault the people who were cheating him was almost overwhelming. Then he looked into their faces, and the rage drained from him. How could he bring himself to fight against these bags of bones? With a weak nod of the head, he held out his hand. The man dropped in a few coins and departed.

Henryk’s career as a smuggler was over almost as soon as it had begun. This first encounter soured him on being a ghetto trader. He would wait until nightfall and go over the wall.

While it was still daylight, the boy took a careful survey in order to find the most appropriate place from which to make his escape. The wall was about eight feet high, so it was advantageous to pick a spot where the ground below was relatively soft. Henryk selected a likely-looking place, then retreated to await darkness.

A cold rain, which began falling late in the afternoon, was coming down in torrents as he lithely mounted the top of the wall. He perched there for a moment, peering into impenetrable darkness so thick that he could not see the ground below him. He listened intently for a few seconds—nothing stirred. Fleetingly he thought, what will be, will be; and he flung his small body into the darkness.

Henryk landed with a soggy thud. To his dismay, he had come down squarely between two guards who were standing close to the wall in an effort to keep dry. His sudden arrival momentarily startled them, and they froze. The boy hit the ground, running as fast as his scrawny legs could carry him.

When the flustered guards regained their wits, they began to cry into the rain-swept evening, “Halt! Halt at once!” Their guns began spitting small darts of flame toward the sound of the youngster’s splashing feet. He could hear the shots and the whine of bullets speeding past him. It was as though the shouts and the bullets had issued a new order for him to hasten his departure. His legs seemed to fly as he scrambled toward the safety of some bombed-out buildings that stood a short distance from the wall.

He managed to reach them before the bullets found him. Diving into the rubble, the young escapee lay listening. Breath came in painful gasps, and his heart raced as though it were completely out of control. A few yards away he could hear the guards groping through the ruined houses in search of their quarry. He pressed his frail body against the debris and waited. In due time the men gave up the hunt and returned to their posts. With their departure, Henryk was up and running again. When he had gone what he considered a safe distance, he sought shelter and waited for the rain to stop.

Now the question was what to do. He was cold, wet, and hungry. Something must be found to eat. After that, he would seek shelter. The rain had stopped when Henryk stepped out into one of Warsaw’s lighted boulevards. Shoppers, delayed because of the rains, were out late. Consequently, many people were on the street. A store owner eyed the hungry youth suspiciously as Henryk paused to browse in front of his shop. Small baskets of fat red apples sat lusciously beside other fruits and vegetables along the sidewalk.

Henryk formulated his plan. The money he had received for the potatoes was of no use to him here. It was currency issued specifically for the ghetto. To offer it to anyone outside the wall would surely betray his identity. Desperation drove him to a decision. He would wait until the proprietor was distracted, then steal something and make his escape.

Henryk wandered slowly to the front of the next shop up the street and feigned interest in the goods displayed in the store window. Soon a woman arrived and ordered some cherries. As the owner turned aside to measure out the purchase, the youngster dashed in, snatched up a basket of apples, and ran up the street. Not far behind, the store owner charged after him, shouting at the top of his lungs, “Stop, thief! Someone stop the thief!”

People along the boulevard saw what was happening. But rather than help apprehend the boy, they stood aside and let him pass. They had no stomach for contributing to the prolonged hunger of one of Warsaw’s waifs. Soon the man gave up his futile chase. Leaving the lighted area, Henryk searched until he found what appeared to be a short tunnel that ran beneath some of the bombed-out buildings. It was partially filled with rubble but was relatively warm. At least it would be a safe place to pass the night.

The small boy sat alone in the dark and munched his apples. Well, he thought, now I am assured of living to see tomorrow.

The next morning the boy whose mother had told him to be a man awakened to a scene that severely strained his youthful powers of manly self-control. Scattered amid the debris choking the tunnel where he had slept lay the grisly skeletons of people who had been killed during the German bombing of the city in 1939. Henryk had spent the night in the company of the dead. As the horrified child fled, it was almost as if something dreadfully symbolic were being projected: For years to come, this little Jewish lad would constantly be fleeing from the presence of death.

For the next few weeks, Henryk attempted to squeeze out a living by carrying heavy bags for travelers who passed through the central train station. This was not much more rewarding than selling potatoes. The police and adult baggage handlers repeatedly chased him and the other boys his age from the station. Tiring of the kicks and threats of his hide-and-seek existence, he decided to leave the city.

With his future a bleak question mark, Henryk took to the roads away from Warsaw, seeking a means to sustain the frail thread of life.