Prayer: The Service Of The Heart

Prayer is not unique to Judaism, yet Jewish prayer is unique. In synagogues around the world, congregants meet together to worship. But Jewish prayer is not confined to a synagogue. On a flight to the Holy Land, it is not uncommon to see Orthodox Jewish men gathering in the back of a 747 as the sun rises in the east, wearing prayer shawls and carrying siddurs (special prayer books) in their hands, much to the amazement of their fellow travelers. As they open their bags of religious paraphernalia, they begin to chant softly and sway gently. At the Western or Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, Jewish prayer can be seen graphically as worshipers recite various prayers, often with great emotion. And what pilgrim to the promised land has not been moved to write a special prayer and insert in into the cracks of the Wall’s huge stones?

Whether in a synagogue, on board a 747, at the Wall, or in private homes, prayer holds a central place for the Jewish people. The next few articles in this series will focus on Jewish prayer, its description, its distinctiveness, and its dynamic.

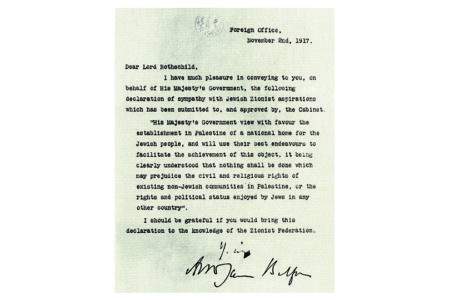

Jewish Prayer: Introduced in the Old Testament

The English word pray is defined by such words as implore, entreat, or even beg. Most people think of the word as asking or petitioning God. The Hebrew word L’hitpalel carries no such idea. At its root is the word pll, which means to judge. Thus, regardless of the kind of prayer, the person praying is, in a real sense, judging himself as he interacts with God.

Jewish Scripture gives numerous examples of individuals crying out, seeking, and inquiring of God in prayer. The Psalmist stated it well when he said, “The Lord is near unto all those who call upon him, to all who call upon him in truth” (Ps. 145:18). It seems clear that the prayers of the Old Testament Hebrew were simple, spontaneous, and selfless. In addition, these prayers were almost always group-conscious and “other”-centered. The prayer offered by Solomon at the dedication of the Temple contains four elements of Hebrew prayer: thanksgiving, praise, confession, and intercession. Formal prescribed prayers, even commanded prayers, were not part of Jewish prayer until the time of the Second Temple.

Jewish Prayer: Interpreted by the Rabbis

Using Deuteronomy 11:12, the rabbis determined that prayer holds a supreme position in Jewish thought, calling it “the service of the heart.” After Herod’s Temple was destroyed, prayer was regarded as a substitute for the sacrifices. Later it came to be considered a means to forgive sin.

Jewish prayer is distinct in several ways. First, it is spoken in Hebrew, a practice preferred although not prescribed. This being the case, the more Orthodox the congregation, the more Hebrew is used in its prayers. Many find this practice frustrating, either because they are unable to read the Hebrew words or because they read the words without understanding what they are saying. However, this practice is defended in the following ways.

- Hebrew is the language of the Torah, the “sacred tongue,” and as such unites Jews as a people.

- The use of Hebrew ensures that Jewish people will feel reasonably at home in their synagogues.

- The use of Hebrew serves as a means of binding the people with the land of Israel.

- The use of Hebrew checks the possibility of total assimilation into a non-Jewish culture.

The second distinctive of Jewish prayer is its fixed liturgy. One rabbi comments that “liturgy unites, theology divides.” It is believed that the use of siddurim (prayer books) affords the worshiper the opportunity to think of things about God that he may not have thought of on his own. In addition, liturgy instills a sense of community as prayers are recited together to God.

The third distinctive of Jewish prayer is that a minimum number of ten men is required to pray corporately. This quorum is called a minyan. The practice is taken from the Torah (Num. 14). There the ten spies were considered a congregation. While private prayer is allowed, it is regarded as a special mitzvah (good deed) to pray as part of a congregation. The importance of corporate prayer can be seen clearly in the rabbinical teaching that if you cannot be present for corporate prayer, you can at least time your private prayers to coincide with those of the congregation. This aspect of Jewish prayer is still another way to remind Jews that they are a social people who can be encouraged by being around one another.

Jewish Prayer: Intensity of the Heart

Central to the concept of a Jewish prayer is kavanah, the devotion that the rabbis direct to God during prayer. It is concentration; it is sincerity; it is praying as though the shekinah (glory of God) is present. Kavanah is a quiet calm and an assurance as people recite the prayers. Maimonides said, “Prayer without devotion is not prayer…He whose thoughts are wandering or occupied with other things ought not to pray…before engaging in prayer the worshiper ought to bring himself into a devotional frame of mind.”

As we have looked at some of the issues of Jewish prayer, we may want to examine our own state of mind as we approach our Father in heaven. May we be unencumbered by wandering thoughts, having our minds set on Him.