Prophet, Priest, And King

If you ask someone to name the founder of Christianity, he or she will probably reply, “Jesus Christ.” Most people think that Jesus was His first name and Christ was His last name. The word Christ, however, is not a name—it is a title. It means Messiah. Therefore, when people use the phrase Jesus Christ, they really are saying Jesus the Messiah. Below that title Christ/Messiah is a deep layer of rich meaning.

The term Messiah is a translation of the Hebrew word mashiach, a verbal noun meaning anointed one. The Greek translation of the word, utilized in both the Septuagint and the New Testament, is christos, from which comes the English word Christ. The Hebrew verb and noun are primarily applied to three types of individuals in the Old Testament period: priests (Ex. 28:41; Lev. 4:3), kings (1 Sam. 12:2; 16:12;), and prophets (1 Ki. 19:16; Ps. 105:15). The idea is to consecrate people for sacred tasks (i.e., to perform special functions in the theocratic program).

Some critical scholars deny that mashiach is ever used in the Old Testament for a personal messiah. Of its 39 occurrences, however, there are at least nine where it could describe some future anointed one in the line of David who would be Yahweh’s king (1 Sam. 2:10, 35; Ps. 2:2; 20:6; 28:8; 84:9; Dan. 9:25–26; Hab. 3:13).

The doctrine of a promised messiah, however, is not limited simply to the term itself. The Old Testament hope of a deliverer who would crush Satan’s head (Gen. 3:15) and be the means of blessing to all mankind (Gen. 12:3) is described in a variety of terms. Some of them are “Son” (Ps. 2:7), “branch” (Zech. 6:12), and “servant” (Isa. 41–53).

Regarding the specific number of promises about the Messiah, there is a wide divergence of opinion. Rabbinical writings refer to 456 separate Old Testament passages used to refer to the Messiah and messianic times (Edersheim, Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah, vol. II, pp. 710–41). One Christian scholar lists 127 personal messianic prophecies (Payne, Encyclopedia of Biblical Prophecy, pp. 667–68). The differences are due to the ways in which the New Testament refers to the Old Testament promises. There are direct messianic prophecies (e.g., Mic. 5:2; Zech. 9:9); typical messianic prophecies, utilizing an immediate referent in the prophet’s day that pointed to the ultimate referent (e.g., the sacrificial Levitical system); and applications of Old Testament concepts to the Messiah (e.g., the reference in Mt. 2:23 to the prophets saying, “He shall be called a Nazarene”). If we limit ourselves to the direct messianic prophecies just mentioned, a conservative number would be approximately 65. The key to understanding the role of the promised Messiah and the main difference between traditional Jewish and Christian messianic views is His dual role of suffering and reigning. While there are many passages that describe a glorious reign for the Messiah (Jer. 23:5–6; 30:1–10; Zech. 14:3 ff), there are other passages that describe His rejection and suffering (Ps. 22; Isa. 53; Zech. 9:9; 12:10; 13:5–7). The New Testament views the suffering and glory passages as fulfilled in Jesus’ first and second comings (Lk. 24:25–27; 1 Pet. 1:10–11).

While the Hebrew Scriptures provide many details about the Messiah, perhaps there is no better way to view the subject than through a grid of His threefold work as a Prophet, a Priest, and a King. It will be seen that Jesus is also presented in this way in the New Testament—as the one who combines all three of these roles in His own person.

Messiah as Prophet

Elijah was commanded by the Lord: “And Elisha, the son of Shaphat of Abel-meholah, shalt thou anoint to be prophet in thy stead” (1 Ki. 19:16). The prophets were often referred to as “mine anointed” (Ps. 105:15). Likewise, the Messiah came to this earth, not only to rule and to redeem, but also to proclaim the truths about divine revelation. This was His role as Prophet—one who declared God’s message. It was Moses who first predicted, “The Lᴏʀᴅ thy God will raise up unto thee a Prophet from the midst of thee, of thy brethren, like unto me; unto him ye shall hearken” (Dt. 18:15). It is important to note that this one must be from the “brethren” of Israel, emphasizing His humanity. While some have seen this prophecy as having its fulfillment only in the order of prophets during Israel’s subsequent history, later information indicates that the Jews in New Testament times were still expecting this eschatological prophet. The Dead Sea Scrolls indicate that the group of ascetic Jews at Qumran were still looking for this great prophet. Notice also the question of the Jewish leaders to John the Baptist: “And they asked him, What then? Art thou Elijah? And he saith, I am not. Art thou that prophet? And he answered, No” (Jn. 1:21).

The apostles, however, understood the real identity of this prophet. Peter boldly proclaimed Jesus as this Prophet-Messiah in Acts 3:22, and Stephen did the same in Acts 7:37. Jesus was the ultimate Prophet, the one who perfectly fulfilled all of the prophetic ideals. No one spoke like He did: “he taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes” (Mt. 7:29). He Himself proclaimed His identity as the Messianic Prophet when He stood before His home synagogue and proclaimed, “The Spirit of the Lᴏʀᴅ is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach” (Lk. 4:18). While Psalm 22 concerns basically the priestly work of the Messiah in His suffering and sacrifice, it also equates this messianic figure with that of the anticipated prophet who would faithfully declare God’s Word: “I will declare thy name unto my brethren, in the midst of the church will I sing praise unto thee” (Ps. 22:22, as cited in Heb. 2:12).

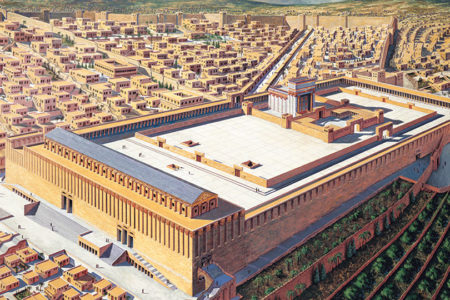

Therefore, Jesus certified Himself as the promised Messianic Prophet by faithfully predicting things that later took place just as He had predicted. Only one example is needed: Jesus predicted the total destruction of the Jerusalem Temple (Mt. 24:1–2); His word was fulfilled in 70 A.D., when the armies of Rome destroyed it. No one else in history qualifies to be the Prophet predicted by Moses. Jesus is that Messianic Prophet.

Messiah as Priest

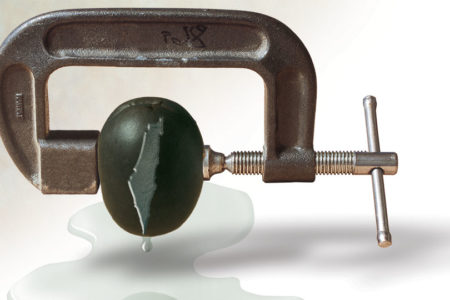

Aaron and his sons, as Israel’s priests, were the second class of ancient Israelites who were anointed with oil (Ex. 29:7; Lev. 4:3). The most basic function of the Old Testament priest was to offer sacrifices. The Messiah’s priestly function is seen both in His work as the sacrificer, who officiates at the altar, and also as actually becoming in His own person the sacrifice, the one who was slain to atone for sin.

The role of the Messianic Priest appears in three ways in the Old Testament Scripture. Psalm 110, quoted in the New Testament more than any other Old Testament passage, states that David’s “Lord” (i.e., the Messiah) is declared by divine oath to be a priest: “The Lᴏʀᴅ hath sworn, and will not repent, Thou art a priest forever after the order of Melchizedek” (Ps. 110:4). The Book of Hebrews appears to be a sermon expounding this great Psalm and its promises of the Messiah’s priesthood, exaltation, and session at the Father’s right hand. Jesus’ being in the Melchizedekan priesthood is shown to be “better” than the temporary and mortal Levitical priesthood (7:11–28). The sacrificial act of the Messiah is also described in terms of Psalm 110 in Hebrews 10:12–14: “But this man, after he had offered one sacrifice for sins forever, sat down on the right hand of God, From henceforth expecting till his enemies be made his footstool. For by one offering he hath perfected forever them that are sanctified.”

The second passage that describes the priestly sacrifice of the Messiah is the “Servant Song”—Isaiah 53—called by many the clearest example of the gospel in the Old Testament. After describing the suffering of the Lord’s “servant,” verse 10 declares, “When thou shalt make his soul an offering for sin.” The Hebrew word asham is used elsewhere for the “trespass offering” (Lev. 5:19). This marvelous acknowledgment of the Messiah’s priestly sacrifice is followed by the statement in verse 12 that He “made intercession for the transgressors”—another priestly function.

One further passage, Daniel 9:24–27, mentions the priestly sacrifice of the Messiah. Space does not permit a full treatment of the amazing chronological aspects of this passage. Suffice it to say that it prophesies, among other things, that “Messiah [shall] be cut off” (9:26). The verb used (karat) is also used for violent death and “cutting the covenant” in many other Old Testament passages (e.g., Gen. 15:18)—all clearly sacrificial language. The verse also states that this sacrificial death of the Messiah would take place before the Temple was destroyed in 70 A.D.

Yes, in light of all of this, Jesus is the Messianic Priest.

Messiah as King

The first king in Israel, Saul, was anointed by Samuel to initiate his role in the theocratic kingdom (1 Sam. 10:1). Thereafter, even in his disobedience, he was “the Lᴏʀᴅ’s anointed” (lit., maschic or messiah, 1 Sam. 24:6). Saul’s successor, David, was also anointed by Samuel (1 Sam. 16:13). Thus, the king joined the prophets and priests in Israel as the Lord’s anointed ones.

However, long before Saul and David, prophetic Scripture had anticipated an anointed king, one whose characteristics went beyond any earthly monarch. Jacob (around 1800 B.C.) and Balaam (around 1400 B.C.) prophesied that the King-Messiah would wield the scepter—gaining the obedience of the people—(Gen. 49:10) and break down human opposition (Num. 24:17). The concluding verse of Hannah’s magnificat is the first passage in which the coming deliverer is specifically called “king”: “The Lᴏʀᴅ…shall give strength unto his king, and exalt the horn of his anointed” (1 Sam. 2:10). This future person cannot be either Saul or David, for this king’s reign will take place in that future age when the Lord shall judge the ends of the earth.

The Psalms are full of references to a future king whose characteristics make it clear that David, as powerful as he was, could have been only the typical prototype of the ultimate king. David referred to the King-Messiah as the Son of God (Ps. 2:2, 7). David also predicted the Messiah’s ascension to the right hand of Yahweh (Lᴏʀᴅ) as David’s Adon (Lord, Ps. 110:1). In the same Psalm, this one is described as ruling in the midst of his enemies after they have been defeated (v. 2). In the same vein, Solomon looked far beyond his own time and foretold the coming of the perfect King whose kingdom would take up where his own had terminated: “He shall have dominion also from sea to sea, and from the river unto the ends of the earth” (Ps. 72:8). In a similar fashion, Psalm 45:6 addresses itself to the divine Messianic King, saying, “Thy throne, O God, is forever and ever; the scepter of thy kingdom is a right scepter.”

Isaiah predicted that the Messianic child would bear the governmental authority upon the throne of David (Isa. 9:7). Micah, however, spoke of the Messiah’s birth in the humble village of David’s family, Bethlehem, rather than in the royal city of Jerusalem (Mic. 5:2). Jeremiah united deity and humanity when he described the reign of King-Messiah: “Behold, the days come, saith the Lᴏʀᴅ, that I will raise unto David a righteous Branch, and a King shall reign and prosper, and shall execute justice and righteousness in the earth. In his days Judah shall be saved, and Israel shall dwell safely; and this is his name whereby he shall be called, ᴛʜᴇ Lᴏʀᴅ ᴏᴜʀ ʀɪɢʜᴛᴇᴏᴜꜱɴᴇꜱꜱ” (Jer. 23:5–6). While most of these promises foresee the glories normally associated with the reign of a king, Zechariah reverted to a more humble royal description: “Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion; shout, O daughter of Jerusalem; behold, thy King cometh unto thee; he is just, and having salvation; lowly, and riding upon an ass, and upon a colt, the foal of an ass” (Zech. 9:9). Balancing these seemingly contradictory descriptions necessitates two comings of that King, first in lowliness (see the fulfillment in Mt. 21:5) and then in glory (see Rev. 19:11–16).

Jesus’ terms of kingship, however, would not be served by a Roman procurator’s view of these matters. In answer to the straightforward question by Pilate, “Art thou the King of the Jews?” (Jn. 18:33), Jesus said, “My kingdom is not of this world; if my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight, that I should not be delivered to the Jews; but now is my kingdom not from here. Pilate, therefore, said unto him, Art thou a king, then? Jesus answered, Thou sayest that I am a king” (Jn. 18:36–37). Although grossly misunderstood by His accusers, it was for this crime that the Messiah was executed: “And Pilate wrote a title, and put it on the cross. And the writing was, jesus, of nazareth, the king of the jews” (Jn. 19:19). Truly Jesus is the Messianic King.

Mention was made earlier of the Qumran authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Their writings make it clear that they understood this threefold role of the Messiah from the Hebrew Scriptures they so venerated. However, they thought that there would be three different Messiahs who would come in the last days: a Messianic Prophet, a Messianic Priest, and a Messianic King. They were on the right track, but they did not have it completely clear. There were not to be three different Messiahs, but one Messiah with three roles. Jesus’ ministry and the way in which His followers believed in Him made it clear that He combined these normally separate roles in His own precious person and work.

Consider a few New Testament passages in which the rubric of Jesus as Prophet-Priest-King makes the passage come alive to the reader. In Hebrews 9:24–28, the word appear occurs three times. “For Christ is not entered into the holy places made with hands, which are the figures of the true, but into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God for us; Nor yet that he should offer himself often, as the high priest entereth into the holy place every year with blood of others; For then must he often have suffered since the foundation of the world. But now once, in the end of the ages, hath he appeared to put away sin by the sacrifice of himself. And as it is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment, So Christ was once offered to bear the sins of many; and unto them that look for him shall he appear the second time without sin unto salvation.”

Or consider John’s description of the Messiah in Revelation 1:5: “And from Jesus Christ, who is the faithful witness [Prophet], and the first begotten of the dead [Priest], and the prince of the kings of the earth [King].”

In this regard, it is interesting to note that there were individual Israelite examples of people who were at the same time both priests and prophets (Ezekiel, Jeremiah) and also a person who was at the same time both a king and a prophet (David). But no examples exist of an Israelite being both a priest and a king (remember that Melchizedek was not an Israelite). In fact, whenever a king tried to serve as a priest, he was punished severely (Saul, 1 Sam. 13:8–14; Uzziah, 2 Chr. 26:16–20). This was because only the Messiah could combine these two functions in His own person. Hear the prophecy: “And speak unto him, saying, Thus speaketh the Lᴏʀᴅ of hosts: saying, Behold, the man whose name is the ʙʀᴀɴᴄʜ; and he shall grow up out of his place, and he shall build the temple of the Lᴏʀᴅ; Even he shall build the temple of the Lᴏʀᴅ; and he shall bear the glory, and shall sit and rule upon his throne; and he shall be a priest upon his throne; and the counsel of peace shall be between them both” (Zech. 6:12–13). “A priest upon his throne”—this was something unheard of in the Israelite economy, something true only of Israel’s Priest-King, the Lord Jesus Christ.

Therefore, the final Messiah would be the ideal Prophet-Priest-King, combining the role of the Prophet, who declared God’s will to mankind; the role of the Priest, who offered a sacrifice to God for mankind; and the role of the King, who alone has the right to rule over mankind as God.

As the anointed one of the Lord, Jesus was, is, and shall be the Prophet, the Priest, and the King. Each of these roles, however, was emphasized at a different time in His redemptive role. During His earthly ministry of teaching and preaching, His role as Prophet was in the forefront (see Jn. 6:14; 7:40). His sacrificial death, resurrection, ascension, and current session at His Father’s right hand brings His role as Priest into view (Ps. 110:1–2; Heb. 4:14; 10:11–12). Following His return to the earth, during His Millennial reign, His role as King will be stressed (Rev. 19:16). The point is that He is always the anointed King, but He will not enter into His public office as King until the Millennium. An Old Testament example of this was the period of time between David’s anointing as King (1 Sam. 16:13) and his eventual enthronement as Saul’s successor (2 Sam. 5:3).

In light of all that has been seen of the offices of the prophet, the priest, and the king in the Old Testament period, and in light of the amazing way in which Jesus fulfills all three roles, may we all conclude with the words of Andrew:

“We have found the Messiah, which is, being interpreted, the Christ” (Jn. 1:41).

Dr. Varner,

I’ve long been of the opinion and have preached that no OT person was allowed to function under all three anointings; prophet, priest, and king. I feel that I have good Biblical gorunds for this position. Is this correct? The one exception would, of course be Melchizedek, whom I judge to be a preincarnate manifestation of Christ, The Eternal King of Jerusalem.

Thank you for your good work on this website and for taking a minute or two to help me.

Larry LaFleur

Sulphur, La.