1 thought on “Students Learn from Ancient Scrolls From the Days of the Vilna Gaon”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Some people have integrity; others don’t. Now is a good time to consider what flag you want flying over Jerusalem.

Dan Brown’s novel has been on The New York Times Best Seller list for two years now, contradicting Scripture. Is it accurate? See for yourself.

Rabbi Elijah was born in 1720. He was a brilliant Torah scholar and kabbalist who left indelible marks on Judaism—not all of them good.

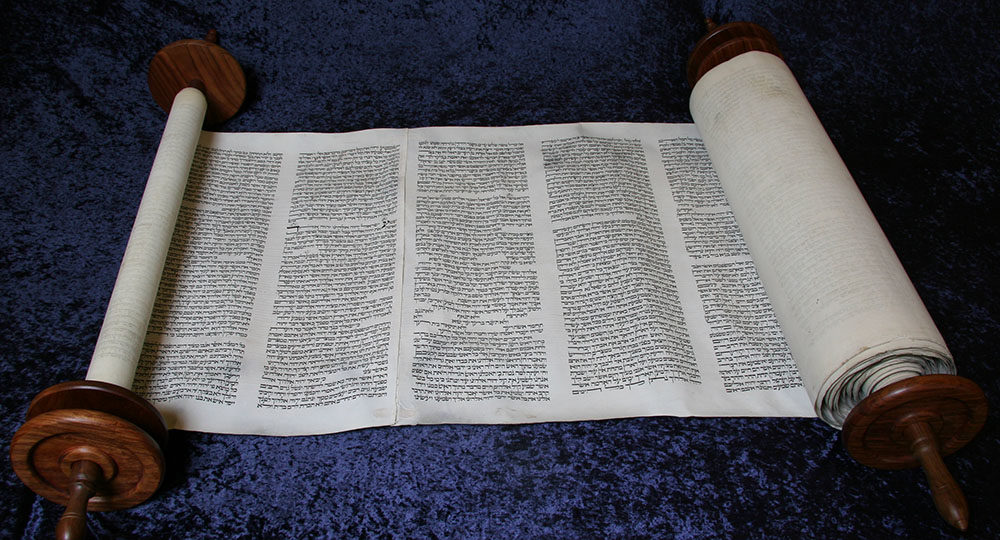

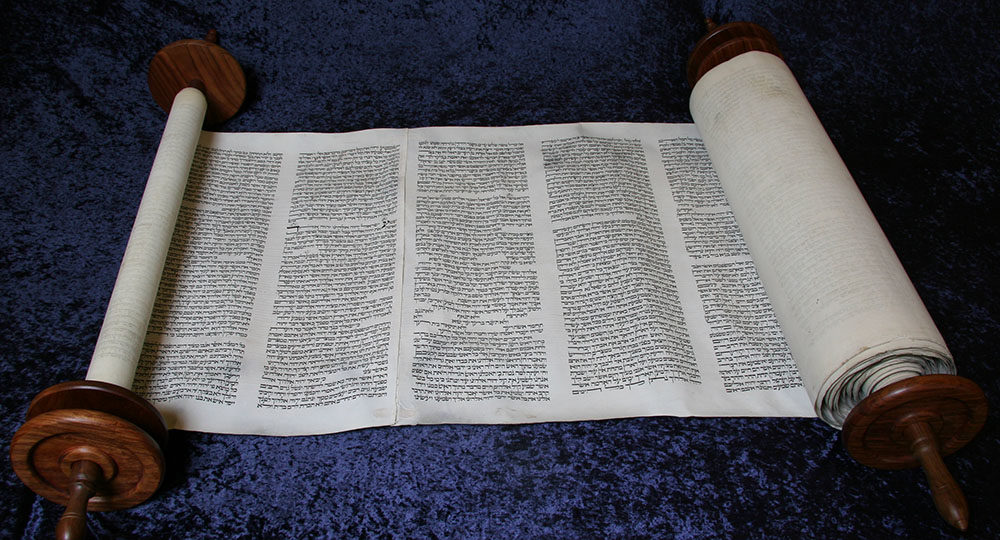

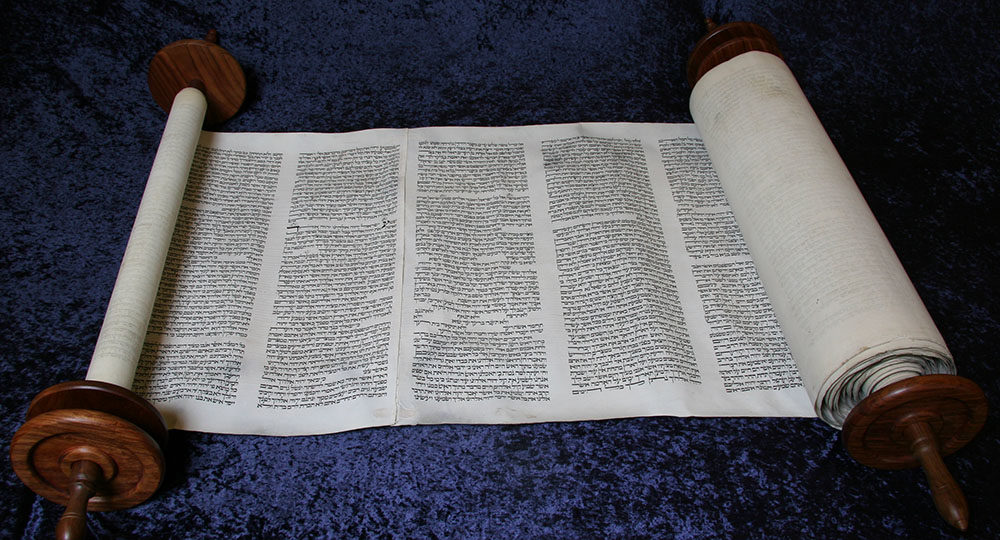

What does an ancient scroll look like? Come into the classroom at Baptist Bible College where students worked on a 300- year-old Sefer Torah. You’ll be amazed!

Everything about them is different. Who are they? What do they believe? This first of three articles explores the intriguing, unusual world of Hasidism.

This is a wonderful Torah Scroll. It is being used at Congregation Beth Messiah in Houston, Texas. I purchased this Scroll from Machon OT in Jerusalem in 2004. Each column of the entire Scroll has been photographed in high resolution and can be studied on my website at:

https://gracetranscendingthetorah.com/tanakh-wip/