Surviving the Holocaust

Through the Eyes of a Child

Ten-year-old Henryk stood in the window looking out for a long time. In the courtyard below he could see small children playing games. The gate through which his mother had left the orphanage seemed disproportionately large against the gathering darkness. At such a young age, Henryk Weichert found himself alone. He did not know why. Nor could this frail Jewish lad begin to comprehend the maelstrom of carnage and outrage through which he and Europe were passing. The Poland a carefree child had known was gone.

It would never be the same again—Adolf Hitler and his manic delusions would see to that.

A short time before, Henryk and his diminutive mother Ruth had walked hand in hand through the streets of Warsaw. Ruth proceeded hesitantly, a small valise in her left hand. Somehow she had wished they could walk past the orphanage into a world free of death and trouble. But it was not to be.

As they parted that day, the anguished mother spoke in carefully measured tones. “Henryk, I want you to make me a promise, one you must always carry with you—a promise you must never forget. Do not tell anyone here that you are a Jew. Because they don’t like Jews here. Be careful what you say, and always remember what I have told you.

“My son, you must learn to be strong. From now on you are no longer my child—now you are a man.”

For a confused small boy and his family, the die was cast. His two brothers were already working their way to an early grave as slave laborers in German war factories. For his mother, father, and younger sister, the next stop on the road to Treblinka would be the infamous Warsaw Ghetto.

Years later, away from the orphanage and still heartsick over the forced separation from his family, Henryk struggled through the slime of the city’s sewers. This was the entrance Warsaw’s young smugglers used to get past the heavily guarded entrances to the place where Jews had been penned up to die. Once inside the ghetto, he would begin the search for his parents.

Starvation and disease were the twin sovereigns of the ghetto. Henryk winced at the sight of emaciated, ragged children with outstretched hands pleading, “I am hungry. Please give me bread.”

Scattered here and there, close to the buildings, were the elderly and the very young, huddled frail bodies inching their way toward the end of physical suffering. Some waited silently, while others lifted feeble hands and uttered pitiful entreaties. Now and then he could hear mumbled prayers for the Messiah to come suddenly and bring deliverance.

The boy stood mesmerized by the variegated smells, sights, and sounds assaulting his senses. Suddenly he became aware of a clattering sound coming slowly up the street. He looked about to see a pushcart attended by two men with handkerchiefs over their faces. Human remains were stacked on the cart like cordwood, as these members of the death crew gathered the bodies of those who had expired during the night. Arms and legs protruded in grotesque gestures amidst expressionless faces that stared blindly, openmouthed, into the autumn sky.

The search for his parents was a vain exercise. Henryk did, however, come across an elderly man who had lived on his street before the separation. “Henryk,” he said, “let me give you some advice. If you stay here in the ghetto, you soon will grow weak like the rest. Don’t die here. Do everything you can to save yourself.”

The old man was right, of course, but surviving the war as one of Poland’s army of street waifs would only prove marginally superior to the squalor and starvation of the ghetto. Numbing winter nights beneath piles of leaves in the forest or shelter in lice-infested barns debilitated every human instinct except the dogged determination to survive. But dodging death took nimble feet and an even more agile brain. A friend Henryk companioned with for a time was lacking in both areas.

No chapter from the bloody pages of the Holocaust magnifies the depravity of the Nazi monsters as does their treatment of children. Henryk’s unfortunate friend fell prey to Nazi-style brutality when he bumped into a German soldier as he ran from a store where he had snatched a few coins from the register. The boy, thought Henryk, looked so Jewish in his appearance that it was as though “he wore the map of Israel on his face.” The soldier cursed loudly and called out, “This little is a Jew! And we know what to do with Jew pigs.”

Henryk felt nauseous as he saw the man reach out to take the boy by the throat and lift him to eye level. The coins tumbled from his hands, his eyes rolled wildly and his tongue was forced from his mouth by the strangling grip of the soldier’s hand. As Henryk turned to leave the scene, the soldier was dragging the dying boy backward up the street.

As waves of Russian troops finally passed through the small town where Henryk occupied a corner in the cellar of a bombed out building, he was struck by the fact that the war was over for him. As he sat in his shelter that night, he looked back over the last five years of his life. He had, he thought, just cause to congratulate himself. Under the most adverse conditions anyone could possibly endure, he had survived. It was a triumph for determination, toughness, skill, and a lightning-quick mind over the instruments of intimidation, privation, and death that had been turned against him. Thousands had died, among them his entire family, but he had prevailed. In his mind, the garland of victory rested firmly on his head when he laid down to sleep that night.

(Taken from the book ZVI)

Editor’s Note: Little Henryk, Jewish war waif of the Holocaust, grew up to become our Zvi whose incredible experiences, now from the streets of Jerusalem, are found in every issue of Israel My Glory.

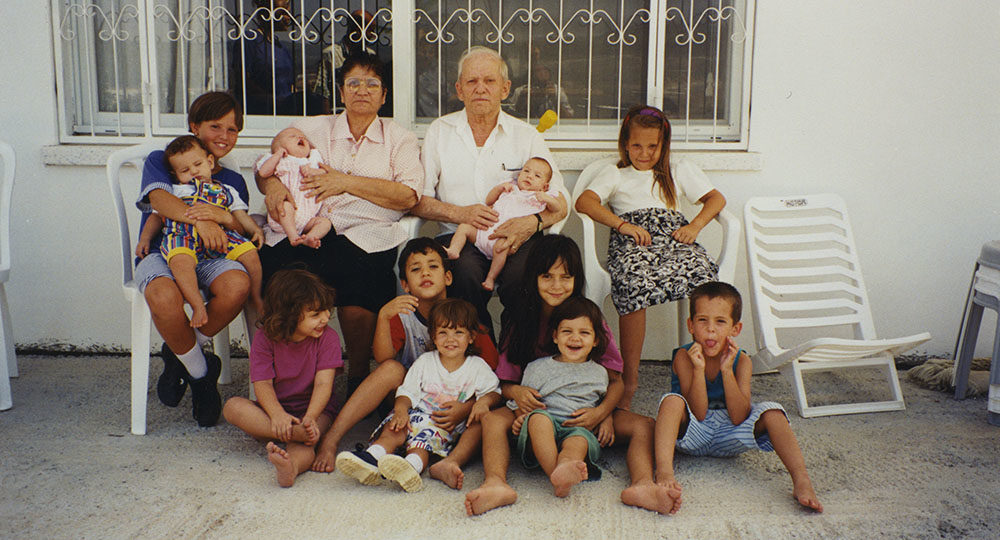

The Lord richly blessed Zvi by replacing the two brothers and one sister he lost in the Holocaust. Zvi and his wife Naomi have three sons and one daughter, the identical family to that of his parents.