The American Jew: Stranger in Our Midst

The 19th century witnessed thousands of European Jews pouring through Ellis Island to their new home in America. They were greeted by words penned by a Jewess, Emma Lazarus, and mounted in bronze on the Statue of Liberty:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shores,

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed, to me.

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

Many were tired, poor, tempest-tossed, yearning to breathe free. Little did they know that the United States would become a golden door to freedom and hold “real opportunity to live in peace and pursue interests that would bring meaning and stability to their lives.

Immigration

The mass of European Jews came to America in three waves. First came the Sephardic (Spanish) Jews, who settled in New Amsterdam. Only 23 came in 1654, but within the next hundred years Jews came from Western Europe to settle in such places as New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Some tried to settle in New England, but the Puritans protested.

By the Revolutionary War, the Jewish population was estimated at 3,000 people and was made up of merchants who settled in the 13 colonies and established five synagogues. Over the years, Spanish Jews largely lost their identity through absorption into the Jewish population or intermarriage.

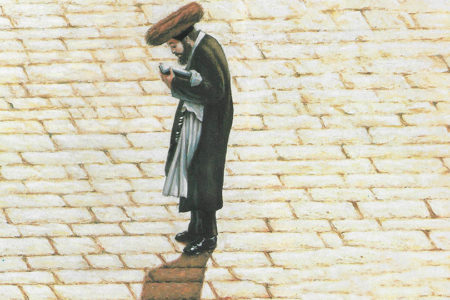

The second wave of Jewish: immigrants comprised poor or middle-class workmen and merchants who came from Germany, Austria, and Hungary between 1815 and 1890. They came to America to escape the resurgence of anti-Semitism sweeping Europe. Most became peddlers in their new homeland, settling in the Southwest and Far West. Business was done by horse and wagon. Often, after finding an acceptable city in which to live; they opened dry goods stores. Although they were neither scholars nor professionals, they had acquired a good European education; they were well-read and progressive in thought. Many embraced Reform Judaism, which came into being around the time of their immigration to America.

The German Jews were instrumental in the establishment of Jewish hospitals and numerous philanthropic institutions. Unlike the Sephardic Jews, they spread across the country rapidly, establishing themselves as leaders in many major cities. Five million German immigrants came during this period, of which 200,000 were Jewish. By 1881, the Jewish population in America had grown to 250,000.1

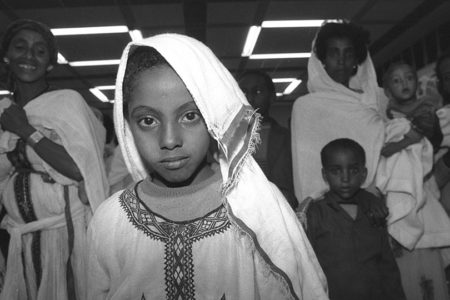

The third wave of Jewish immigration to America poured out of the ghettos and villages of Eastern Europe. Two million came from Russia, Poland, Austria, and Romania between 1881 and 1920. They left Russia because of their deep poverty, governmental oppression, and mob violence incited by the pogroms, which began in 1881.2

Those who came through Ellis Island settled on the lower east side of New York City. They lived in a 12-square-mile section of Brooklyn. Most were under 50 years of age, energetic and aggressive, eager to carve out a new life in America. Many were deeply religious and fanatically loyal to Judaism. They had to adapt quickly from an autocratic society to a democracy, peasant life to skilled factory work, medieval suppression to freedom of expression. They became workers on New York’s lower east side, mostly in the sweatshops of the garment district. Although they started as garment workers, artisans, peddlers, and shopkeepers, in one generation their children were studying law and medicine in American universities. They were on an upwardly mobile track moving to better neighborhoods and advancing from working class tradesmen to proprietors and professional people. They were quick learners and progressive in establishing a better life in the new world. By 1921, however, new immigration quota laws drastically cut the flow of Jews to the United States.

Influence

Some people believe that Christopher Columbus was of Jewish heritage, but little evidence has been put forth to validate this claim. Columbus himself claimed that he was an Italian Catholic. It has been proven that Columbus obtained much assistance for his voyage from Jewish mapmakers, scientists, astronomers, and financiers such as Luis Santangel and Gabriel Sanchez. Some claim that when Columbus discovered the new land, he expected to find the so-called “ten lost tribes of Israel.” Five of the 120 men who sailed with Columbus were Jewish. In fact, the first man to set foot ashore was a Jew, Luis de Torres (who spoke Hebrew, Chaldean, and Arabic) because it was believed he could converse with the Asians whom Columbus expected to encounter.

Jewish influence was first introduced to the new land by Puritans arriving in 1620, who structured their new society on the Old Testament teachings of a theocracy. Early constitutions, such as the Plymouth Colony Code of Laws in 1636, the Massachusetts Code in 1647, and the Connecticut Code in 1650, were based on the laws of Moses. Hebrew was taught at Harvard as early as 1655. The first Thanksgiving celebrated in America was patterned after the Jewish Feast of Tabernacles.3

During the American Revolution, 40 Jewish soldiers fought under George Washington. A Jew named Haym Salomon gave great sums of money to finance the war. He was never repaid for his generosity and died at the age of 44—bankrupt. A statue in his honor stands on Wacker Drive in Chicago.

American culture has benefited from hundreds of Jewish people in the fields of literature, medicine, physiology, chemistry, economics, journalism, history, poetry, drama, music, inventions, and cartooning, to name just a few of their many endeavors. There have been at least 35 Nobel Prize winners and 92 Pulitzer Prize winners among American Jews, not to mention the many others who have enhanced life in this country by their accomplishments.

Business

Upon arriving in America, Jews immediately entered light industry, such as the garment trade. They often engaged in small, high-risk businesses with a minimum of capital, which, if successful, would provide a potential for high growth. Most became self-employed or worked for other Jewish people to escape the discrimination experienced in Europe. Statistics indicate that two-thirds of all Jews today enter the professions or small businesses of every kind.

Contrary to popular belief, Jews are conspicuously absent in management level positions in big corporations, banking, insurance companies, and the transportation and utility industries. In the past, a club atmosphere among many groups within major companies tended to exclude Jews from higher managerial positions, but this is quickly disappearing.

Jews prefer occupations in which they are not dependent on others. They work harder than many other ethnic groups to succeed or prove themselves because of prejudice or discrimination. The following attitudes have helped many Jews become successful in business: (1) a willingness to defer personal pleasures for future benefits; (2) taking personal responsibility for decisions; (3) saving and investing income in a free-enterprise system; (4) opening one’s own business rather than working for others; (5) creating business opportunities rather than waiting for them to come their way.

Religion

The Jews who immigrated to America were either Orthodox, Reform, or not affiliated with any religious group. Soon a more moderate position emerged between the Orthodox and Reform known as Conservative Judaism.

Today less than 55% of American Jews belong to a synagogue, 70% attend synagogue only four times a year, 25% never attend, and 70% do not keep a kosher home. Only about 10% of the Jewish population attend synagogue services on any given Sabbath. In this country, 11% of the Jewish population are Orthodox, 40% are Conservative, 30% are Reform, 12% do not specify which branch they embrace, 1.5% claim to be atheist or agnostic, and 5.5% have no identification.

There is not a single theological position with which all Jews agree. Someone has stated, “Ask a Jewish person a theological question, and you may receive two answers and five more questions in return.” There is no standard theological position accepted by every branch of Judaism. Jews emphasize “deeds rather than creeds.” Deeds in civic, social, and humanitarian endeavors are what count among the Jewish people. Jews equate a good Jew with being a good person. A good Jew is one who is ethical in his behavior, with a civic spirit of bettering mankind. Today, being a good person makes one a good Jew. In the past, being a good Jew made one a good person.

Social Standards

Jews tend to congregate in certain geographic areas in order to maintain synagogues and communal institutions, and they attempt to create an environment of community for their children because of similar associational inbreeding and common interests. Their cultural traits cause them to develop mutual ties of acquaintances, friendships, and affections. Often they have been denied residence in certain areas where assimilation into the Gentile culture was difficult.

Naturally, mutual family values, religious beliefs, and similar occupations provide a stick-together mentality in the Jewish culture that dates back to the early days of their establishment in America. Anti-Semitic remarks, prejudice, and fear of discrimination have, over the years, served as catalysts to hold Jews within their own communities. Throughout their history, Jews have tended to avoid situations that subject them to personal injury because of anti-Semitism.

Jews do, however, contribute socially outside of their culture more than any other group, proportionate to its population, in the areas of art, public affairs, music, theater, literature publication, and social causes.

At least 30% of the Jewish population are married to Gentiles. Intermarriage is more frequent among upwardly mobile professional Jews, rural or small town Jews, Reform and unaffiliated religious Jews, and those from broken homes who lack contact with the extended family. More Jewish men than women intermarry today.

Education

Education has been the cornerstone of Jewish survival throughout their history. From biblical times, Jewish people have been called “the people of the book” and have stressed the value of education for a number of reasons. First, secular education was closed to Jews in the past, but public schools in America made it possible for them to receive the needed instruction to progress in their new world. Second, education provides opportunities for better jobs in society and thus a better standard of living. Third, Jews feel they must have more to offer in order to overcome prejudice and discrimination. Fourth, the Jewish family and religion put great emphasis on education, for the person with knowledge will be able to change society for the better.

In the 1920s, many eastern colleges established quota systems for Jewish students. When a Jew was admitted, he faced social ostracism by other students and fraternal organizations. For these and other reasons, Jews have become better educated than any other ethnic group.

Politics

American Jews are strong adherents to constitutional guarantees that provide individual rights, freedom, and social welfare for all people. In the past 60 years, about 70 to 90% of the Jewish population have tended to vote as liberal Democrats. A past history of inhumane treatment suffered in other countries has caused Jews to be involved in liberal social issues and racial equality. This has led to their interest and involvement in foreign policy and international affairs more than any other group in America.

Anti-Semitism in America

Jews have enjoyed personal rights and less persecution in America than in any other nation during the Diaspora. But there still exists an undercurrent of anti-Semitism flowing throughout America, which is often felt by the Jewish community.

During the colonial period, old European stereotypes were manifested. Jews were considered mysterious, outsiders, and heretics. During the Civil War, newspapers and political leaders falsely accused Jews of aiding the enemy, smuggling, profiteering during the war, and draft dodging in both the North and the South.

In the 1870s, anti-Semitism took the form of social discrimination. Jews were refused admittance to certain hotels, clubs, places of residence, private schools, institutions, and associations that conferred prestige and status. This was a form of social discrimination by the wealthy class of Gentiles designed to keep Jews in their place.

Anti-Semitic literature began to appear in the 1920s, such as The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and The Dearborn Independent, a magazine owned by Henry Ford. In 1924 the Ku Klux Klan came into being and was a major source of harassment to the Jewish community through their speeches and literature.

The 1930s brought an upsurge of anti-Semitism, spurred by the Depression and the rise of Nazism.

In the postwar years of the 1940s and 1950s, anti-Semitism was isolated to a fringe group. There was little persecution manifested during this period as a result of Jews being absorbed into middle-class suburban society, a decline of social discrimination against Jewish people, and the legislation of civil rights.

Today, anti-Semitism still exists through such groups as the neo-Nazis, Skinheads, Ku Klux Klan, Liberty Lobby, and groups within the Aryan Nations organization. “During 1988, 823 episodes of vandalism and desecration and 458 acts of harassment, threats and assaults against Jewish individuals, their property and their institutions resulted in the highest number of anti-Semitic incidents reported in more than five years. The reports of anti-Semitic incidents of all kinds on American college campuses during 1988 have more than doubled.”4

Jews in Rural America

Two-thirds of the Jewish people in rural America went there for business reasons. They were either traveling salesmen or peddlers who settled down in towns that accepted them in the circuits they serviced. Usually they started general stores, which often grew into department stores. Others opened scrap metal and paper businesses. Still others were refugee physicians who fled to America, and, finding it difficult to become established in urban communities, they opened practices in rural America or were placed there by refugee agencies and professional groups. Although they lived in rural areas, most viewed themselves as urban in lifestyle. Even though they had little exposure to their religion and culture, most considered themselves Jewish in both.

Gentiles in the rural areas viewed their Jewish neighbors as different from other Jews because they did not conform to stereotypes, were more assimilated, and were quieter and more gentle in social dealings with their neighbors. Many rural Jews saw themselves as ambassadors to the Gentiles, obligated to present a positive image of their people to many Gentiles who had never met a Jewish person. Over 80% of rural Jews interacted with Gentiles both socially and as members of local organizations. Most tried to have the best of both worlds by being bicultural—involved in community organizations and activities while remaining Jewish. The secret of a Jew living happily in a small town was to assimilate quietly with an honest and equitable attitude toward the people in the community.

America has provided a golden door of opportunity for Jewish people from all nations. In it they have found a refuge from social, political, and religious oppression. They have been assimilated or have remained isolated in their Jewishness without suffering the stigma so often experienced in other countries. In return, Jews have made use of their gifts and talents to bring unprecedented blessing to America in many areas, including medicine, science, engineering, music, and entertainment.

The blessing of God has been showered upon the landscape of this country according to the biblical affirmation, “I will bless them that bless thee, and curse him that curseth thee: and in thee shall all families of the earth be blessed” (Gen. 12:3). May we continue to allow the Jew the same constitutional freedoms that this country has avowed to all men. Our continued blessing depends upon it!