The Betrayal of Balfour

“I think that the God of Israel is with us.”

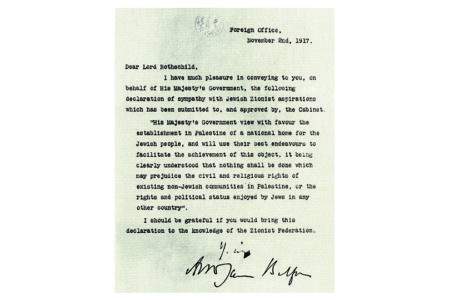

So wrote Chaim Weizmann in 1919. Both God in heaven and Balfour in England viewed “with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” It would take the sovereign power of Almighty God to fulfill the desire of the Jewish people for their own state. British reluctance and Arab resistance would have to be broken. The history of the period between the Balfour Declaration in 1917 and the establishment of the new Israeli state in 1948 reads like the highest of drama. The following four elements describe some of the tears and shouts of joy that led to realization of the dream of a Jewish state, a dream that at times seemed more like a nightmare.

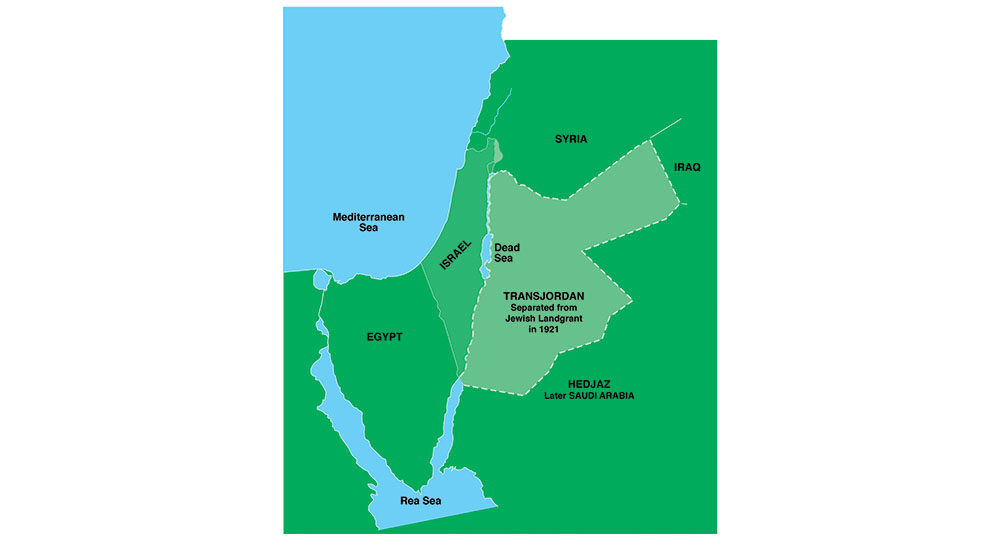

Redrawn Boundaries

The mandate given to Britain in 1920 at the San Remo Conference accounted for much more land than was commonly thought of as Israel. The boundaries of this British Mandate included territory on both sides of the Jordan River, not only the West. Trouble arose as Abdullah, grandfather of Jordan’s present King Hussein, attempted to aid his brother Feisal in regaining power in Syria, which was under French control. In 1921 Winston Churchill offered Abdullah the area east of the Jordan River in an attempt to keep peace between England and France. In return for Abdullah’s cooperation, Britain would supply money and trained advisors for this new territory, known as Transjordan. Churchill even promised eventual independence to this as yet unestablished country. Remarkably, Balfour’s original plan included this land for the development of Jewish agriculture. Even Abdullah seemed surprised at this unexpected gift. He wrote, “God granted me success in creating the Government of Transjordan by having it separated from the Balfour Declaration which had included it.” In spite of his action on Transjordan, Churchill stated his case for Zionism when he spoke to Arab leaders.

It is manifestly right that the Jews…should have a national centre and a National Home…And where else could that be but in the land of Palestine, with which for more than 3000 years they have been intimately and profoundly associated? We think it would be good for the world, good for the Jews, and good for the British Empire.

Current discussion of a Palestinian state never mentions the original state designated for Arabs in Palestine—Transjordan. Independent since 1946, today it is known as the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Only God knows how history would have been written if all of the territory included in the original Mandate, before Churchill gave away Transjordan, had been considered in the years of turmoil that followed.

Jewish Immigration

Sir Herbert Samuel was appointed as the first British High Commissioner of Palestine in 1920. He was Jewish and also a Zionist. Under his direction, thousands of Jewish immigrants settled in the land. In each of the years between 1920 and 1923, about 8,000 Jews entered Palestine. In 1924 the number jumped to 13,000 and the following year to more than 33,000. Sadly, many Jewish people came to Palestine because they could go nowhere else. America closed its doors to mass immigration in 1924. During these years Jerusalem and Haifa saw their Jewish population double, and Tel Aviv became a city. A firsthand witness provides this vivid picture:

There was no more moving sight in those days than the arrival at Haifa or Jaffa of a Mediterranean ship carrying the Jews from Europe: the spontaneous cries of joy at the first sight of the shore, the mass chanting of Hebrew hymns or Yiddish songs usually began raggedly over all the boat and sometimes swelling into a single harmony…a man seizing hold of a stranger and pointing with tears of joy to the approaching land crying, “Zion! Zion!” and “Jerusalem!”

In 1925 the statesman Arthur Balfour, then 77, made his first and only visit to the land forever associated with his name. He spoke at the opening of the Hebrew University, the first completely Jewish university in the world. Jewish presence in the land continued to grow slowly but steadily. Under the watchful eye of British High Commissioners Samuel and later Plumer, Arabs and Jews lived in peace. It was, tragically, the calm before the storm.

| Year | Jewish Population | Arab Population |

| 1922 | 84,000 | 590,000 |

| 1931 | 174,000 | 760,000 |

| 1933 | 450,000 | 900,000 |

Arab Revolts

Late in 1928 a new High Commissioner, Sir John Chancellor, arrived in Jerusalem. With him came a changed spirit in administrating the Mandate. Chancellor, not sympathetic to the Jews, allied himself more closely with Arab leaders. Back home in Britain, the situation changed as well. In 1929 a new government arose that had no connection with the Balfour era or sympathy for his Declaration.

The British betrayal of the Jews was also rooted in the underground—underground oil beneath the vast Arabian deserts. With a rising industrial society and its growing need for petroleum in the coming war, peace with the Arabs made economic sense to the British.

Arab power in Jerusalem centered on a single religious and political leader—Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti (official interpreter of Muslim law). Seeing an opportunity in the British ambivalence toward the Mandate, the Mufti incited fear and violence against the Jews, which resulted in multiple Arab attacks on Jews. “The Jews’ ultimate aim is the reconstruction of the Temple of King Solomon on the ruins of the Haram ash-Sharif, the El-Aqsa Mosque, and the Holy Dome of the Rock,” said the Mufti. His unfounded fear led to the charge that Muslim holy places were threatened. Following another plan of attack, one Orthodox Christian archbishop testified, “According to Christianity, we are the new Israelites, we are the new people of God.”

The British refused to allow Jews to arm themselves while these attacks continued for several days in and around Jerusalem. Arab terror also struck Jewish residents of Hebron, the holy city where Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob are buried. In the end, 133 Jews were killed and 339 were wounded.

After a lull of several years, violence against the Jews surfaced again with renewed force. Arabs no doubt observed that the despised Jewish race was vulnerable to the Nazi exterminators. Why not finish the task themselves, they reasoned, and rid the land of Jewish invaders as well as British infidels? With backing from the Nazis, the Arabs struck throughout the land in 1936. Not only were Jews the target of terror, but the British forces felt the Arabs’ rage as well. When Arabs murdered the District Commissioner of Galilee, the British considered it a declaration of rebellion against their rule.

With no official army, Israel was defended by its own underground military organization, the Haganah. Some Jews regarded the posture of defense as insufficient and formed an aggressive paramilitary force, the Irgun. At times the Irgun’s indiscriminate retaliation brought criticism from fellow Jews, but these fighters were seeking to keep the Jewish homeland alive. The British sought and received aid from these Jews in response to Arab attacks. Orde Charles Wingate, a Bible-believing Zionist and British commander, trained Haganah volunteers in covert operations.

The situation looked bleak. With the Arabs determined to push the Jews into the sea and the British determined to please both Arabs and Jews, plans for a homeland for persecuted Jews brought more persecution. From the pen of a fervent Zionist, Vladimir Jabotinsky, came this lament in 1936: “The main asset in all our Zionist venture, England as we know her up to yesterday, has disappeared. Sometimes I feel like Sinbad the Sailor…must have felt when he established his ‘national home’ on a little island…and the island proved to be a whale.”

The British White Paper

Alarmed at the escalating brutality of both Arabs and Jews, the British appointed a commission led by Lord Peel to investigate the roots of the problem and recommend a solution. The British Peel Commission concluded in 1937 that the British Mandate was clearly unworkable. Only a divided Palestine could permanently settle the violence. “Partition seems to offer at least a chance of ultimate peace,” it stated. A Jewish state and an Arab state, side by side, was the official prescription for this ailing land. (The present situation in 1996 bears a striking similarity to this proposal.)

The Jews accepted this news because it upheld their desire for a Jewish state, although at a reduced size. The Arabs vehemently opposed any such coexistence in the same land with the Jews. This opportunity for a Palestinian Arab state side by side with a Jewish state was crushed by the Arabs themselves! Their violence soon led to the next step.

To avoid upsetting the Arabs and partitioning Palestine, the British government, now led by a new Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, compromised again. The White Paper of 1939 was the official policy for the Holy Land. Its provisions included denial of the partition plan, denial of a Jewish state, prohibition on the sale of land to Jews, and limitation on Jewish immigration to 15,000 people each year for five years. After that it would cease altogether! With such a blatant reversal of the Balfour Declaration, it was no wonder that the Jews felt betrayed. David Ben-Gurion aptly declared that asking the Jews to stop their immigration into Palestine would be like asking a woman in labor to stop giving birth. The Arabs demanded that Jewish immigration cease, and the British agreed. The Balfour Declaration had served its time. Chamberlain’s policy of “appeasement” soon led to his own resignation. Within six months of the White Paper, Britain was involved in World War II. Churchill’s criticism expressed his own country’s betrayal:

This pledge of a home of refugees, of an asylum, was not made to the Jews of Palestine, but to the Jews outside Palestine, to that vast, unhappy mass of scattered, persecuted, wandering Jews whose intense, unchanging, unconquerable desire has been for a National Home…That is the pledge which was given, and that is the pledge which we are now asked to break…This is the abandonment of the Balfour Declaration; this is the end of the vision, of the hope, of the dream.

But he was wrong. It was not the end of the dream. That dream survived, but for the coming years it would be interrupted by a nightmare.