A Hero Named Janusz Korczak

God loves children. His heart especially goes out to orphans, and He commands us, “Defend the fatherless” (Isa. 1:17). During the Holocaust, one man in particular did just that.

He was born Henryk Goldszmit in 1878 in Warsaw, Poland. Henryk’s parents were ethnically Jewish but practiced little Judaism. They were also wealthy. However, Henryk’s childhood was anything but pleasant. His father verbally abused him. His mother pampered and stifled him. And when Henryk was 11, his father began to have a series of nervous breakdowns, impoverishing the family. When Henryk was 18, his father died in a mental asylum.

These experiences shaped Henryk’s lifelong cause. He despised the tyranny the powerful often exercise over the weak, the rich over the poor, adults over children; and he made it his mission to reform society and help those in need.

To fulfill his mission, Henryk went into medicine, specializing in pediatrics. While studying at the university, he would charge exorbitant fees to his wealthy patients so he could go into the slums and treat the poor at little cost.

During these days, Henryk also began to write and publish his experiences among the destitute, bringing attention to their plight. He also adopted the more Polish-sounding name of Janusz Korczak, by which he became known throughout Poland as a caring doctor and advocate for children. “I tell you,” he wrote, “I’ve never seen a crueler sight than a drunk beating a child or a kid begging in a tavern, ‘Papa, come home.’”1

In 1912 Korczak made the difficult decision to leave his practice at a children’s clinic to become the doctor and director of a new Jewish orphanage in Warsaw that housed 100 children. After World War I, he added a second orphanage to his responsibilities, one for non-Jewish children.

Korczak ran his orphanages according to the “Children’s Republic” he outlined in his famous work, How to Love a Child, in which he stressed the importance of respecting children and allowing them to govern themselves. Although some of his methods may be questionable for use in the home, they proved successful in his orphanages. A survey spanning 20 years showed 98 percent of the orphans he worked with grew up to be productive, stable citizens.

Korczak wrote, taught, and gave anonymous radio addresses regarding children and their needs. He visited the Holy Land twice and was planning a third visit, possibly to stay, when in September 1939 Germany invaded Poland.

When Warsaw was overthrown, Korczak was forced to move his orphans into the newly created Warsaw Ghetto. Five hundred thousand Jews (100,000 of them children) were squeezed into an area only one square mile in size. For two years Korczak and his staff attempted to care for his children. He scrounged for food, went door-to-door begging for donations, and improvised medical treatments. To retain some semblance of normalcy and keep morale up, Korczak maintained daily routines, even giving recitals and play performances.

In 1942 Korczak kept a three-month diary. It was found years later. In it he wrote, “I exist not to be loved and admired, but myself to act and love. It is not the duty of those around to help me but I am duty-bound to look after the world, after man.”2

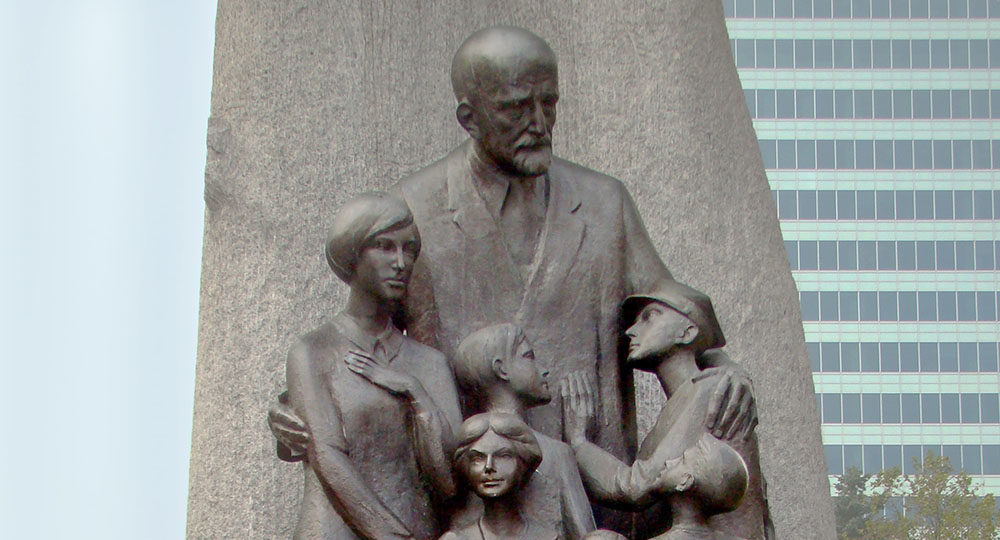

In July 1942 the Nazis began transporting the ghetto’s inhabitants to the Treblinka death camp. On August 5, with himself in the lead, Korczak and his 200 orphans marched four abreast, heads held high, to the awaiting trains. Despite earlier offers of personal exemption and escort to safety, Korczak remained with his charges. “You do not leave a child at night who is sick or in need. I have two hundred orphans; in a time like this I will stay by them every minute,” he said.3 Korczak was last seen helping his children once more—onto the trains.

Though never married, Korczak left a lasting legacy. The apostle James wrote, “Pure and undefiled religion before God and the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their trouble” (Jas. 1:27). Janusz Korczak, although not a Christian, nor even a practicing Jew, certainly exemplified the spirit of this verse and set an example for all to follow.

ENDNOTES

- Cited in Mark Bernheim, Father of the Orphans: The Story of Janusz Korczak (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1989), 66.

- Janusz Korczak, Ghetto Diary (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 69.

- Bernheim, 131.