China & Israel: Inscrutable Relations

Israel was the first Middle East country to recognize Communist China. Beijing returned the favor by being the first non-Arab state to recognize the Palestine Liberation Organization.

Contradiction is universal and absolute. It is present in the process of development of all things and permeates every process from beginning to end.

—Chairman Mao’s essay “On Contradiction,” August 1937

On May 18 China’s ambassador to Israel, Chen Young Long, was summoned to Jerusalem from his embassy in Tel Aviv by the deputy director-general of Israel’s Foreign Ministry, Raphael Schutz, for an unprecedented reprimand.

Israel was chagrined that a diplomat in the Chinese Embassy charged to liaise with the Palestinian Authority (PA) had held meetings with Mahmoud Zahar, the foreign minister of the PA’s Hamas-led government. Schutz told Chen that Israel would not tolerate “a situation in which official diplomats stationed on its soil hold talks with terror elements.”

He warned Chen that the diplomat involved risked expulsion from Israel as a persona non grata and that Israel was none too pleased about media reports that China had invited Zahar to visit in June.

Chen later told Israel Television that the diplomat involved in the contacts with Hamas was actually assigned to China’s consulate in Ramallah.

Either way, Israelis find it bothersome that Beijing has no compunctions about embracing the Hamas-led PA. We’re also disappointed that China has proven so unhelpful just when the civilized world is trying to come up with a unified stance against Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons.

If, however, you were to step back and take a longer view of Chinese policies in the Middle East, particularly in connection with the Arab-Israeli conflict, you would have the impression that Beijing wants decent relations with Israel, as well as a stable Mideast.

Indeed, the very fact that there is a Chinese ambassador stationed in Tel Aviv who can be summoned to Jerusalem for a diplomatic dressing-down reflects China’s evolving and complicated role in the region.

Every country’s foreign policy is the result of complex domestic and international factors. No single rationale—not even the quest for oil to provide energy for China’s fast-growing economy—entirely explains the Chinese attitude toward Israel.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was pro-Palestinian when China’s limited oil needs were satisfied by importing petroleum from Burma and Indonesia. And it remained pro-Palestinian even when Beijing became energy independent in the 1970s. In contrast, now that China imports 58 percent of its oil from the Middle East—11 percent from Iran—its attitude toward Israel has never been friendlier.

Given the vast cultural gulf between Chinese and Western civilizations and the extraordinary differences between China (population 1.3 billion) and Israel (population 7 million), making sense out of Chinese foreign policy is not easy.

This much, however, can be posited: The Chinese attitude toward the Arab-Israeli conflict has always been based on a combination of Chinese nationalism, changing Communist ideology, Beijing’s perception of its geopolitical interests (including the quest for oil), and superpower competition.

Long before there was an “occupied West Bank,” China embraced the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) cause full throttle. Indeed, while Ahmed Shukeiry, the first head of the PLO, held meetings with China’s Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong in Beijing in 1965, few in the West even knew the PLO existed. China, however, greeted Shukeiry as if he were a head of state. Beijing even declared May 15—the date Palestinian Arabs commemorate Israel’s birth as their nakba (“catastrophe”)—as Palestine Solidarity Day.

Speaking as a self-appointed sage of national liberation, Mao told his PLO guests in 1965, “Do not tell me that you have read this or that opinion in my books. You have your war and we have ours. You must create the principles and ideology on which your war stands.”

That being said, China did all it could to help the Arabs battle Israel. Over the years Beijing provided the PLO with weapons, training, and logistical support through its embassy in Beirut, Lebanon. China, in fact, became the first non-Arab state to recognize the PLO. In 1965, it welcomed Rashid Jarbou as the PLO’s permanently stationed diplomatic representative in Beijing.

After the 1967 Six-Day War, China referred to Israel as a puppet regime of American imperialism. It opposed UN Resolution 242, which ended the war, partly because it was the outcome of a compromise between Moscow and Washington, but also because it implicitly recognized Israel’s right to exist in secure boundaries.

With the Palestinian Arabs of Judea, Samaria, and Gaza living for the first time under Israeli rule, China encouraged the PLO to launch a “people’s war of liberation” against the “occupation.” But the Arabs did not manage to do so until the first intifada, which they began in December 1987 and ratcheted up to an even more vicious scale during the current, second intifada that began in October 2000.

China always sided with the Palestinian Arabs. It didn’t matter if they were fighting Israel or “reactionary” Arab regimes, such as Jordan in 1970 during Black September; Beijing viewed the PLO as part of a revolutionary vanguard.

But revolutions don’t last forever. As the Cultural Revolution culminated in 1976, China began inching its way toward accepting bourgeois international norms.

Beijing made and accepted overtures from the United States. It joined the UN as a permanent member of the Security Council. And gradually, Beijing began to lose some of its blind faith in the PLO as an organization—though never in the justice of the Palestinian-Arab cause.

The Wall Cracks

Beijing began sending signals that, although it blamed Israel for the conflict, it was not entirely comfortable with the PLO’s onslaught against civilian targets. The Palestinians had launched their international terrorist campaign in earnest with a 1968 attack on an El Al airplane flying out of Athens, Greece. The Chinese seemed to think that sort of criminality was inconsistent with how liberation movements were supposed to behave.

China also rightly suspected the PLO was becoming too cozy with the Soviet Union and its KGB secret police. But China’s loss of patience with the PLO didn’t translate into sympathy for Israel.

In fact the Chinese media described the surprise attack on the Jewish state on Yom Kippur 1973 as an attack by Israel on Egypt, Syria, and the Palestinian Arabs.

And the Chinese naturally blamed it all on Soviet intrigues.

Nevertheless, by early 1975, a subtle and incremental shift in China’s understanding of the Arab-Israeli conflict could be discerned. Foreign Minister Chiao Kuan-hua made a “secret speech,” arguing that “Israel came into existence only after having disappeared from this globe for more than 1,000 years. It is a fait accompli. We cannot repatriate the Palestinians expelled [sic] thereby creating an Israeli refugee problem.”

The Chinese were understandably surprised—everyone was—by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s historic decision to accept, in November 1977, Prime Minister Menachem Begin’s invitation to visit Jerusalem and address the Knesset.

With Sadat’s visit as a turning point, and with Mao now dead and buried, Chinese policymakers embarked on a long, slow journey from wholeheartedly embracing the Arabs’ intransigent position of “no peace, no negotiations and no recognition” toward favoring a negotiated settlement between Israel and its neighbors.

The signing of the Israel-Egypt peace treaty in 1979 cast Palestinian rejection of the Jewish state as too extreme for a China now led by the pragmatic Deng Xiaoping. When China refused to denounce Egypt, despite direct pleas by Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, Fatah cofounder Salah Khalaf (also its liaison with the international left) retaliated by openly condemning China for its February invasion of Vietnam.

Talks of Guns

China, whose armed forces had done less well than expected in their invasion of Vietnam, suddenly discovered that Israel could be an excellent source of battle-tested weaponry. Thus China’s desire to modernize its armed forces instigated reported clandestine contacts between Beijing and Jerusalem that surfaced in the 1980s.

China wanted it both ways. While making overtures to Israel, it still reportedly supplied the PLO with free weapons and ammunition to help the Palestinians maintain their “Fatah land” enclave in southern Lebanon.

Nor did China’s diplomatic support for the Palestinian position wane. But the tone was changing. Communist Party leader Hu Yaobang used the opportunity of a visit by Jordan’s King Hussein in 1982 to urge the Arab states to recognize “the Israeli people’s right to peaceful coexistence.”

And in 1984, China and Israel reportedly signed a secret $3 billion military deal channeling Israeli arms to the PRC.

This military relationship, however, didn’t inhibit Premier Zhao Ziyang, during one of Arafat’s many visits to China, from continuing to lash out against Israel for refusing to recognize the rights of the Palestinian people and for not “handing back the Arab lands they are occupying.”

China finally went public with its Israel relationship in 1985 when it welcomed a large trade delegation of Israeli businessmen from the medical and budding hi-tech sectors.

The tide was changing. Israel’s consulate reopened in Hong Kong (then still a British colony), academic exchanges were initiated, and tourist offices were established. And Chinese diplomats stopped shunning their Israeli counterparts at the UN and other international gatherings.

The start of the 1990s saw academic ties further strengthened. The Chinese made it easier for their academics to visit Israel, and Israeli scientists found it easier to travel to China; agricultural and technological exchanges blossomed, and a developing flow of Diaspora Jewish tourists to China further underscored the sense that positive change was in the air. Like other countries interested in currying favor with Washington, China’s leadership appeared to think it wise to seek out the friendship of the American-Jewish community.

Diplomatic Relations

Finally, almost anticlimactically, diplomatic relations were established between China and Israel in January 1992. A diplomatic struggle that Israeli Ambassador David Hacohen had initiated in Rangoon, Burma, decades earlier had belatedly come to fruition. (See “How China Shifted Toward the PLO”)

China now found it possible to maintain cordial relations with Israel while maintaining support for a Palestinian state—not in place of Israel, but alongside it. Xinhua, the official Chinese news agency, described the September 1993 mutual recognition by Israel and the PLO as “an important turning point in PLO-Israeli relations and a historic breakthrough in the peace process in the Middle East.”

Xinhua explained the deal as a natural progression of the Palestinian cause rather than a revolutionary turn of events. It said Israel had adopted a “realistic policy” that at last recognized the PLO, while Arafat (supposedly) had rejected terrorism and recognized Israel’s right to exist.

The agency commented that the Oslo deal would “serve as a step toward a peaceful settlement of the Palestinian issue” and foster overall stability in the Middle East.

Significantly, Beijing opposed the activities of PLO hardliners who denounced Oslo, such as Foreign Minister Farouk Kaddoumi. The road to peace, Kaddoumi was told on a 1994 visit to China, would require Palestinian flexibility.

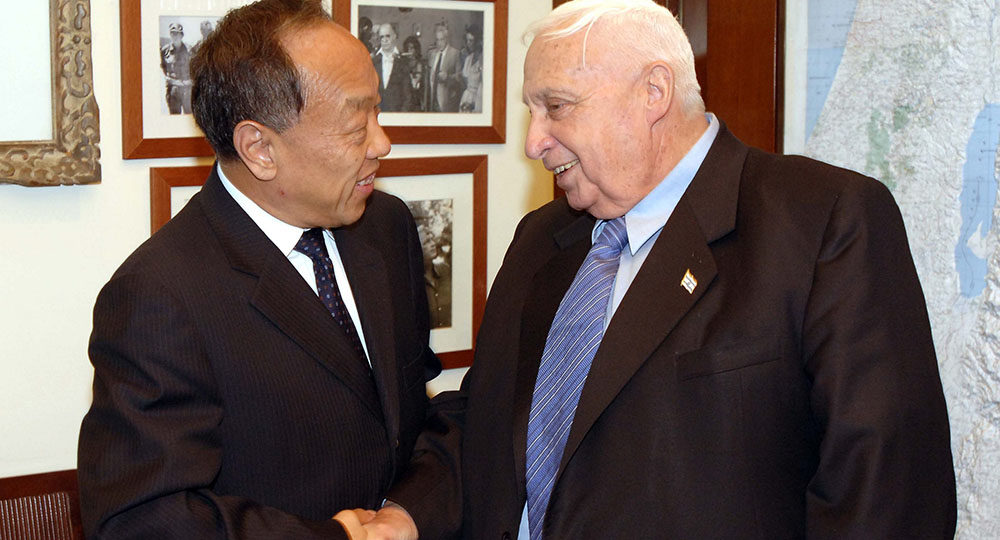

The Israel-China relationship continued to develop, and in April 2000 then-President Jiang Zemin became the first Chinese head of state to visit Israel and the Palestinian Authority. It was a remarkable event, considering China’s long-standing involvement in Arab-Israeli affairs.

After Arafat launched the second intifada at the end of 2000, he traveled to China, among other places, seeking support. The Chinese urged “utmost restraint on the part of both Israel and Palestine, and especially Israel.”

There was no question that Chinese sympathies remained solidly with the Palestinians. Nor did Israel’s cancellation (under intense U.S. pressure) of the $250 million Phalcon early-warning radar system sale in 2000 endear Jerusalem to Beijing.

But unlike in the “bad old days,” Arafat’s visit to China could now be followed by an Israeli leader’s visit there.

In 2002, for instance, Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres led a delegation to Beijing that sought to placate Chinese disappointment over the collapse of the Phalcon deal. (Israel paid China $300 million in compensation for canceling the sale.)

These days the China-Israel relationship is mostly characterized not by politics, but by economics. Scores of Israeli businesses are active in China, and Chinese investment in Israel is aggressively encouraged. Last year bilateral trade surpassed$2.6 billion.

A Voice for Moderation

Although economics can never completely displace politics in the Middle East, today’s China wants to see a region that is stable so that Beijing can pursue its primary global interest: not national liberation or revolution, but economic growth.

I’m not suggesting that the Chinese don’t want commensurate political and military clout to go hand-in-hand with their burgeoning economic power. But nations that do business together, whose economies are tightly connected by the global system of trade, have a natural incentive to promote good relations and stability.

It remains to be seen whether Chinese foreign policy decision-makers can be persuaded that an Islamic regime in Iran armed with nuclear weapons threatens not only Israel and the West but also China’s long-term interests.

Similarly, China’s long-standing sympathy for the Palestinian cause helps explain its willingness to embrace even a Palestinian regime led by Hamas. Yet even here, China is using its Palestinian card to urge moderation.

In May, Zhai Jun, director-general of West Asian and North African Affairs of China’s Foreign Ministry, openly called on Hamas “to respect agreements previously signed with Israel, to recognize Israel and to return to talks.”

That is also the message, promises Chinese Ambassador to Israel Chen Young Long, that Hamas leaders will get every time they visit Beijing.

Such an attitude is a proverbial journey of a thousand miles from the days when China was fueling Palestinian violence and denying Israel’s right to exist.

The more Chinese officials are exposed to the Israeli narrative, the better our chances of fulfilling David Hacohen’s dream of harmonious relations between our two ancient civilizations.