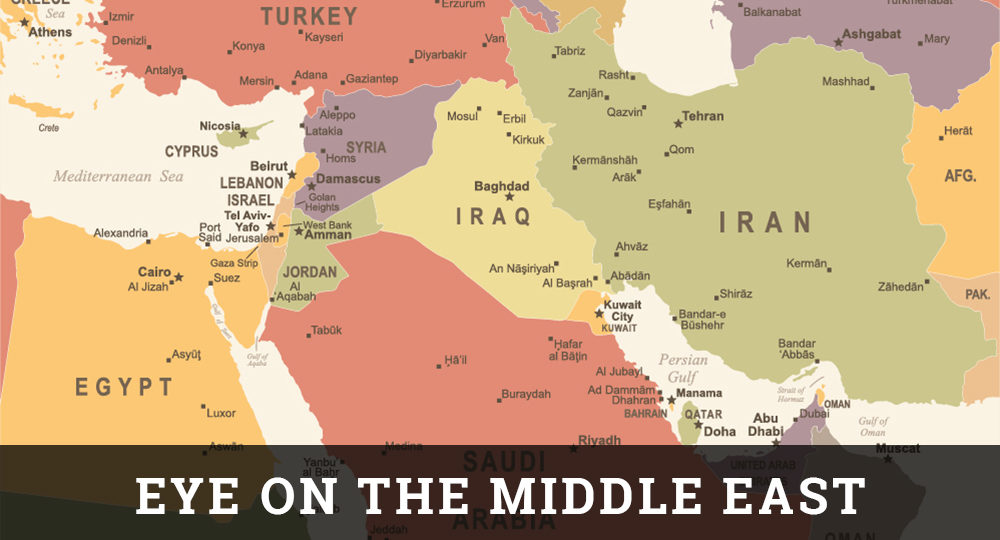

Eye on the Middle East Aug/Sep 2000

Ehud Barak’s government is on the verge of collapse. With the sporadic departure of parties from his coalition, the prime minister faces the distinct possibility of calling early elections. He vows that in that case, he will put together a much more stable administration, perhaps without the nettlesome ultra-Orthodox religious parties. The nation as a whole seems to agree that the government is in need of major surgery but with quite a different twist than envisioned by Mr. Barak.

In a recent Gallup poll, the majority of respondents indicated they would prefer a national unity government of both the One Israel and Likud parties, minus the religious parties. Among those who identified themselves as supporters of the prime minister, 67.5 percent said they favor the unity government concept without the religious additives.

Some heavy-hitters in the government support the idea. The popular Natan Sharansky, minister of the interior, has called for the establishment of a national unity government, explaining that it is the only solution to the current political situation. Foreign Minister David Levy weighed in on the subject in a June 15 article in The Jerusalem Post (Internet Edition): “I believe that the situation makes it necessary for all of us to find the way to national unity at a difficult time like this.”

In view of the critical decisions Israel is now making, a national unity government seems to make sense. And it would not be the first time such an arrangement has been tried. In a unity government, the major parties, One Israel and Likud, would share the office of prime minister on a rotating basis. The cabinet would be comprised of members from both parties, hopefully providing a consensus representing a more balanced national view.

One serious problem the State of Israel has endured since its inception has been the necessity of including ultra-Orthodox parties in order to establish a viable coalition. But their inclusion has allowed these minority, ultra-religious groups to hold the government hostage to their demands in the name of political survival. This situation often worked to the detriment of Jewish believers and Christian organizations. Israelis who are not Orthodox have long called for a government less beholden to those espousing what they consider radical views—views they feel impinge on how they conduct their daily lives.

The biggest hurdle to a national unity government may be the Likud Party. To this point, party leader Ariel Sharon has said no to the idea. He prefers to hold new elections and attempt to regain the power lost when Ehud Barak defeated Likud incumbent Benjamin Netanyahu.

But politicians have a way of assessing shifting winds in the light of what’s possible. Therefore, both sides may arrive at the conclusion that a national unity government is the way the wind is blowing and make a new start toward achieving a genuine national consensus on peace.