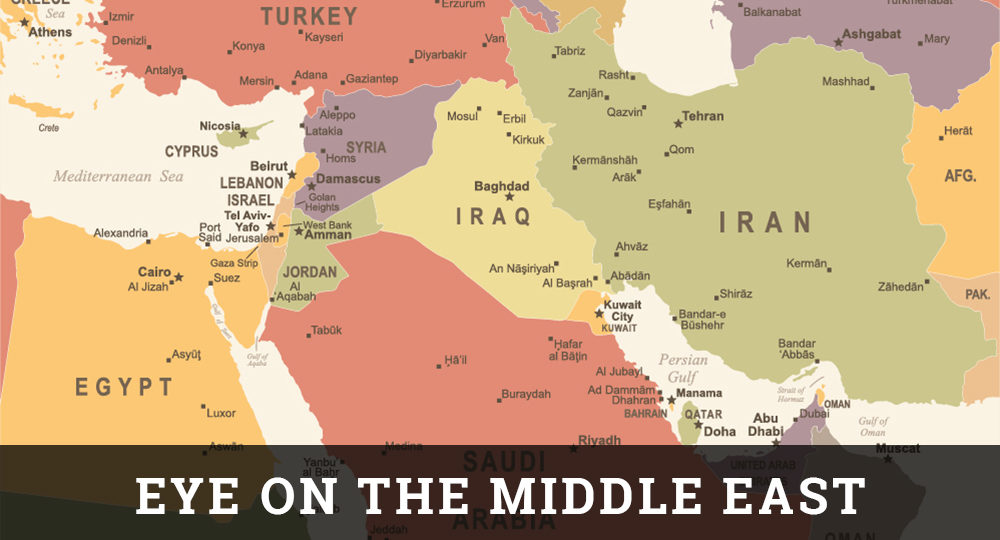

Eye on the Middle East Mar/Apr 2005

Late last year a number of positive developments appeared to be taking place in the Middle East. For starters, Egypt’s president Hosni Mubarak freed an Israeli Druze who had been convicted of spying for Israel and sentenced to 15 years in prison. Israel had consistently claimed there was no basis for the charges and that Azzam Azzam’s incarceration had proved a sticking point in the already cold relations between Israel and Egypt. The release, however, along with word that Egypt will soon dispatch an ambassador to Tel Aviv, had a positive effect on Israelis.

Furthermore, mubarak announced a determination to assist in stabilizing the Gaza/Israeli border and stopping palestinian terrorists from smuggling weapons into Israel from the Sinai.

At the same time, the Jordanians were offering their assistance to help broker a settlement of Palestinian-Israeli disputes and mediate negotiations between the parties.

Not to be left in the dust, Libya invited a Likud member of the Israeli Knesset, Moshe Kahlon, who is Libyan born, to lead a delegation to visit Libya and prepare the way for better relations with Tripoli.

Syrian president Bashar Assad also displayed a desire to get in on the action by announcing that he was ready to negotiate peace with the Israelis without pre-conditions—something the Syrians had always insisted on in the past.

So why, one might ask, this sudden turn of events and attitudes? Why this sudden willingness, at least on the surface, to let bygones be bygones and move into another, more benign, period of history?

For the Egyptians, there was the matter of betrayal in the October bombing of the Hilton Hotel at Taba on the Egyptian-Israeli border. Egyptians, Israelis, and wealthy palestinians had all vacationed there without incident. The unprovoked terrorist attack left 34 dead: nine Egyptians, five Israelis, and 20 others who, in all probability, were palestinians and remain unidentified. This event demonstrated unequivocally that there are no allies in the world of radical Islamic terrorism. Egypt’s leaders are as much targets as innocent Israeli civilians.

Then there was the matter of George W. Bush’s clear victory in the 2004 November elections in the United States. Radical elements in the Middle East and elsewhere had fondly hoped for a less resolute, more accommodating, appeasement-oriented administration in Washington. But, as is often the case, they underestimated the mindset of the American people, believing that Americans would cave under pressure from threats on their personal safety and be disinterested in anything beyond their own personal well-being. That was a big mistake. Grassroots Americans believe in the principle of freedom of choice, which initiated the birth of this republic, and are willing to stand by leaders who have a clear understanding of what liberty for all people is all about.

Finally, the successes of American policy in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Israel send a clear signal to the entire Middle East that America is not a paper tiger. Democracy and freedom are serious commitments, and we have the determination, even by force if necessary, to afford people the opportunity to express themselves about who will lead them in the future.

When formerly totalitarian regimes begin to realize they can no longer submerse their people beneath a blanket of ignorance and suppression, change may begin to take place.

The important thing to know is this: America has stood as a beacon for the oppressed for well over 200 years. And if freedom means anything, it means the same thing for every person on the planet. And we can ill afford to fail in our obligation to procure it for people who so desperately need it.