Eye on the Middle East Mar/Apr 2006

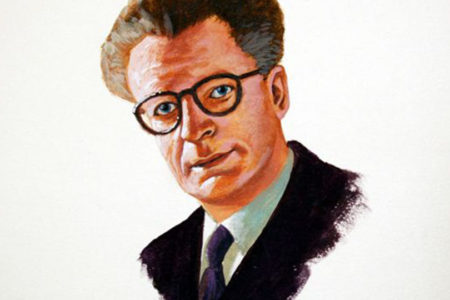

When Israel’s prime minister, Ariel Sharon, was stricken with a devastating, career-ending stroke in January, an era came to an end. Sharon was the last of the giants who have fallen to the ravages of time and the stress of living perpetually on the edge of personal and national survival. Although some will disagree, Sharon was an inspirational national hero who was willing to risk it all for what he perceived to be the good of his beloved homeland.

Born in 1928, Sharon grew up in the maelstrom of war and terrorism. At 14 he joined David Ben Gurion’s Haganah force and served with distinction in the 1948 War of Independence. He later became the architect of Israel’s settlement policies, urging Israelis to possess as much of the land as possible before international pressure and intervention drew the map of the new Middle East.

Among the great milestones in his illustrious military career was his contribution to Israel’s overwhelming victory during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Staring at Israel’s possible demise after Syria and Egypt launched a devastating surprise attack, Ariel Sharon led the counterattack in the Sinai, which ended the Egyptian dream of destroying Israel. Sharon’s forces encircled the Egyptian third army, crossed the Suez Canal, and were outside Cairo when the world demanded a ceasefire.

The smashing defeat of the Egyptian army no doubt convinced Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat that further attempts to wipe Israel off the face of the Middle East were futile and led to the stunning sight of Sadat standing at the podium in Israel’s Knesset in Jerusalem in November 1977, declaring his desire to end the bloodshed and seek peace. Although it would eventually cost him his life, Sadat’s courage and understanding that waging war with Israel was a pointless enterprise began the process for peace. Ariel Sharon played a significant role in Sadat’s decision.

Although he has been portrayed as a hard-bitten, uncompromising child of the right, his biography and personal relationships tell quite another story. In many respects, he embodied the “new Jew” on which the state of Israel was founded. He was born in what is now Israel; therefore, he qualified as a Sabra: hard and prickly on the outside but soft on the inside, like the fruit of the Sabra cactus that symbolizes Israel’s national identity.

Our personal encounters with Mr. Sharon always fell on the side of affability. He had an acute awareness of the friendship of evangelical Christians and their vital importance to the Zionist mission to secure the unalterable rights of the Jewish people to a national homeland in the Middle East. When a group of Christian leaders met with him in Washington last fall, he was personable, humorous, and every bit a leader and friend who was approachable and eager to hear our opinions. Unlike many politicians who put in an appearance with an obvious eye toward a quick get-away, the prime minister never seemed hurried or impatient.

More than a few Zionist Christian friends were uncomfortable with the Sharon disengagement plan that, it was feared, would sacrifice too much of Israel’s God-given land without procuring peace. Now those hard decisions will be left to others.

But whatever one may think about Ariel Sharon’s politics, this great man will always hold an irretrievable place in Israel’s history, one not likely to be held by anyone else.