Hear! O Israel

An overview of the book of Micah and the times in which it was written.

Listen to Chris Katulka’s interview with Tom Davis about this article (begins @ 10:35).

The book of Micah is one of the 12 Minor Prophets in the Bible—minor not because of content but because of size. The Minor Prophets cover similar themes as the other Prophets, but they also emphasize social justice and true worship.

The books are shorter than the Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, and 1 and 2 Kings); the Major Prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel); and the works of Moses, who was also a prophet (see Deuteronomy 34:10 and Luke 24:27). Moses’ books (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) are labeled Torah (Law).

Micah is also one of the nine pre-exilic Minor Prophets, meaning it was written before the destruction of Solomon’s Temple in 586 BC and the Babylonian Captivity. The remaining three are post-exilic, written after some of the Jewish people returned from Babylon.

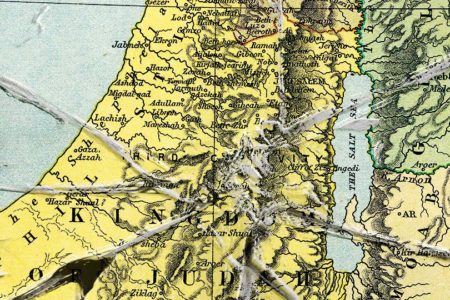

The prophet Micah came from Moresheth (Possession) in the rolling foothills of the Promised Land, about 23 miles southwest of Jerusalem, near ancient Philistia. The area was also called Moresheth-Gath (Possession of Gath), not to be confused with Mareshah, a few miles away. Moresheth is also 17.5 miles west of Tekoa, the hometown of the prophet Amos, whose ministry 50 years earlier likely affected Micah greatly.1 (See Amos 2:12; 7:16; and Micah 2:6.)

Moresheth’s main characteristic was that it was a relatively remote, rural farming community that lay close to the observable Gentile world. Consequently, Micah ministered primarily to the common people of the southern kingdom of Judah. His older contemporary, Isaiah, prophesied in Judah’s capital city of Jerusalem, while Hosea prophesied in the northern kingdom of Israel, whose capital was Samaria.

Most of Micah’s message is about Jerusalem, however, not the rural folk of his hometown. Though he mentioned the coming judgment on the northern kingdom (1:1, 5–6), he did so primarily to warn Jerusalem, encouraging it to repent.

The word Israel occurs 12 times in the book, but in most cases it appears to be used generically for all 12 tribes of Israel, not merely for the northern kingdom.

Micah ministered during the reigns of Judean Kings Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah (v. 1). Therefore, his ministry is dated from 730 to 700 BC.

His name is short for Micaiah. The following names are all related: Michaiah, Micaiah, Michael, Michal, Michah, Micha, Micah, and Mica, with 27 people in Scripture having a form of that name.2 They include the archangel Michael and two women: King Saul’s daughter given to David in marriage (1 Sam. 14:49) and the mother of a king of Judah (2 Chr. 13:2).

His name is short for Micaiah. The following names are all related: Michaiah, Micaiah, Michael, Michal, Michah, Micha, Micah, and Mica, with 27 people in Scripture having a form of that name.2 They include the archangel Michael and two women: King Saul’s daughter given to David in marriage (1 Sam. 14:49) and the mother of a king of Judah (2 Chr. 13:2).

Most of these individuals are only mentioned in passing. One, however, is prominent: the prophet Micaiah the son of Imlah, who predicted the death in battle of the northern kingdom’s wicked King Ahab (1 Ki. 22; 2 Chr. 18).

Micah’s name means, “Who Is Like Jehovah.” The words could be phrased like a question (“Who is like Jehovah?”), expecting the answer, “No one!” There is a play on words on the name in Micah 7:18: “Who is a God like You, pardoning iniquity and passing over the transgression of the remnant of His heritage? He does not retain His anger forever, because He delights in mercy.”

Micah’s theme is judgment followed by blessing. The book can be outlined based on the three times the prophet declared, “Hear!” (Shema! 1:2; 3:1; 6:1):

- Judgment Coming for Samaria and Jerusalem (chaps. 1—2).

- Judgment on Leaders and Blessings From the Ultimate Leader, the Messiah (chaps. 3—5).

- Judgment Justified and Blessings Predicted (chaps. 6—7).

Isaiah and Micah ministered through the period when the northern kingdom tried to force Judah to join a coalition against the Assyrians. The ungodly kings of Judah (such as Ahaz) displeased the Lord by trying to protect themselves through military might and treaties with Assyria and Egypt. These human efforts were doomed to fail; and by 701 BC, the erstwhile allies, the Assyrians, had conquered every city of Judah except Jerusalem.

By then, godly Hezekiah sat on Judah’s throne. In the Assyrian records (a clay monument called the Taylor Prism), King Sennacherib bragged that he had “shut him up like a caged bird in his royal city of Jerusalem.” Fortunately, instead of panicking, Hezekiah called upon the Lord with Isaiah’s and Micah’s encouragement. God delivered Jerusalem, killing 185,000 Assyrian soldiers while they slept.

Micah condemned the idle rich (chap. 2); oppressive government (chap. 3); and hypocritical, ritualistic state religion (chap. 3). He did so mostly using Hebrew poetry, with its emphasis on parallelism. Micah 2:13 provides a descriptive title for the Messiah, Ha Poretz, or “The Breaker” (the one who goes ahead, breaks down obstacles and leads the way).3

Micah 2:12; 4:7; 5:3, 7–8; and 7:18 use the concept of the remnant. The Hebrew word is shear, as in Isaiah’s son Shear-Jashub (“Only a Remnant Shall Return”), so named to warn Ahaz that only a remnant would return if he continued to make treaties with Assyria instead of calling on the Lord for protection (Isa. 7:3).

Micah 4:8 refers to Migdol Eder, the “Tower of the Flock,” which is described as being near Bethlehem in Genesis 35: 19, 21. Micah 7:19 is the basis for the Tashlich ceremony before the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), where Orthodox Jews even today symbolically cast their sins into the sea: “He will again have compassion on us, and will subdue our iniquities. You will cast [tashlich] all our sins into the depths of the sea.”

Interestingly, about 100 years later, the prophet Jeremiah never alluded to or quoted Isaiah, but he quoted Micah 3:12 when everyone wanted to kill him (Jer. 26:8):

Then certain of the elders of the land rose up and spoke to all the assembly of the people, saying: “Micah of Moresheth prophesied in the days of Hezekiah king of Judah, and spoke to all the people of Judah, saying, ‘Thus says the LORD of hosts: “Zion shall be plowed like a field, Jerusalem shall become heaps of ruins, and the mountain of the temple like the bare hills of the forest.”’ Did Hezekiah king of Judah and all Judah ever put him to death? Did he not fear the LORD and seek the LORD’s favor? And the LORD relented concerning the doom which He had pronounced against them. But we are doing great evil against ourselves” (vv. 17–19).

We can also wonder which prophet quoted the other in Isaiah 2:2–4 and Micah 4:1–3. With the exception of only a few words, the passages are identical:

Now it shall come to pass in the latter days that the mountain of the LORD’s house shall be established on the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hills; and peoples shall flow to it. Many nations shall come and say, “Come, and let us go up to the mountain of the LORD, to the house of the God of Jacob; He will teach us His ways, and we shall walk in His paths.” For out of Zion the law shall go forth, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. He shall judge between many peoples, and rebuke strong nations afar off; they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore (Mic. 4:1–3).

JOEL: THE DAY OF THE LORD

Read more about Joel’s prophetic warnings to Israel in Joel: The Day of the Lord by David Levy.

The analogy of war and the plowshare actually predates both Isaiah and Micah, occurring in the reverse in the book of Joel: “Prepare for war!…Beat your plowshares into swords and your pruning hooks into spears” (Joel 3:9–10).

More than 700 years after Micah’s time, when Herod the Great asked the religious rulers where the Messiah was to be born, they quoted Micah 5:2: “So they said to him, ‘In Bethlehem of Judea, for thus it is written by the prophet: “But you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are not the least among the rulers of Judah; for out of you shall come a Ruler who will shepherd My people Israel”’” (Mt. 2:5–6).

In Matthew 10:21, 35–36, Jesus quoted Micah 7:6 as He prepared His disciples for the hardships of their ministry.

Important predictions in Micah include the 722 BC exile of Israel’s 10 northern tribes (1:6), the 701 BC Assyrian attack on Judah (v. 9), and one of the most monumental events in Jewish history: the 586 BC destruction of Jerusalem and the nation’s deportation to Babylon (3:12; 4:10; 7:13). This last prediction is particularly significant because Babylon was not a major power in Micah’s lifetime. It was under Assyrian domination.

Though Micah is numbered among the Minor Prophets— only seven chapters long, 105 verses—it is a wellspring of important information.

ENDNOTES

- E. A. Leslie, “Micah the Prophet,” The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, ed. George Arthur Buttrick (New York, NY: Abingdon Press, 1962), 3:370.

- Ibid., 369–374.

- C. F. Keil, The Minor Prophets, in C. F. Keil and F. Delitzsch, Commentary on the Old Testament (1866–1891; reprint, Peabody, MA: 1996, Hendrickson), 10:304.

Thank. you for such a Wonderful article and publication!!!

So fascinating. I understand so much more since reading this article even though I have read the Bible 60 years. Time designation is a big help as of late. Thank you so much for helping me grow. God bless Israel. God bless the United States of America.