In Quest of the Holy Cow

The Ordinance of the Red Heifer

It was the only sacrifice for which the animal had to be a special color. It was the only sacrifice that had to be performed outside the camp instead of on the altar. It was the only sacrifice that required the ashes of the burned animal to be kept. It was the only sacrifice that purified others while rendering unclean those who performed it. These are just a few of the unique peculiarities of the sacrificial ritual of the red heifer described in Numbers 19:1–22.

An ancient Jewish commentary reflected on the unexplainable characteristics of the ritual in this way: “Solomon was wiser than all men, but when he came to the section of the red cow he admitted, ‘I said, I will get wisdom, but it was far from me.’”1

This strange ordinance has created a mysterious awe that remains until today. Currently, a search is on for a jar that the digger hopes will contain the ashes of the last red heifer killed before the fall of the Temple in 70 A.D. Before that issue is examined, however, we should understand what the Bible and Jewish tradition have stated about this holy cow and its significance.

The Red Heifer in the Bible

The instructions for the ordinance of the red heifer are found in Numbers 19 and were given to Moses during the wilderness wandering. The passage follows the account of the death of those involved in Korah’s rebellion (Num. 16:31–50) and immediately precedes the record of the death of Miriam (Num. 20:1). Therefore, the ordinance had its beginning in a context of death in the wilderness. Perhaps the defilement caused by the deaths of so many Israelites prompted this ordinance.

Since the red heifer was not mentioned among the detailed laws regarding sacrifice and ritual cleansing in the Book of Leviticus, some interpreters have argued that the ordinance was only for the temporary purpose of cleansing Israelites defiled by touching dead bodies during the wilderness wandering. The ancient Israelites, however, understood it as a continuing ordinance.

The ritual began by finding an unblemished red cow on which a yoke had never been placed. The Hebrew term is Parah adumah (lit., red cow). The fact that it was to be unyoked led to the translation “heifer” in the English Bible. Eleazar, the priest, led the cow outside the camp, slaughtered it, and sprinkled some of its blood toward the Tabernacle seven times. The entire animal was then burned, and a mixture of cedar wood, hyssop, and scarlet material was cast onto the pyre. The resulting ashes were gathered and kept in a clean place outside the camp. The purpose of the ashes was to ritually purify anyone who had come in contact with a dead body. Before that person could worship in the Tabernacle, he had to be sprinkled with a mixture of the ashes and flowing (lit., living) water. Any unclean person who refused to be cleansed in this way defiled the Tabernacle and was cut off from the assembly. One interesting consequence of the procedure is that even though people were ritually cleansed through the sprinkling, the one who sprinkled the water became unclean until the evening. This is a summary of the biblical regulations given in Numbers 19:1–22.

The Red Heifer in Jewish Tradition

The Mishna is the basic collection of Jewish oral laws and traditions. It was written around 200 A.D. but preserves traditions established before the birth of Christ. Discussions on the Mishna by the rabbis produced another written commentary, the Gemara. Together these written discussions are called the Talmud. An entire tractate of 12 chapters in the Mishna, entitled “Parah,” is given over to describing the practices related to the ritual of the red heifer. Some of these regulations are as follows:

- If only two black or white hairs were on a red cow, it was considered invalid (Parah 2:15).

- Rabbi Meir declared that the ashes of the first red heifer lasted from Moses until the exile to Babylon. Ezra then sacrificed the second (ca. 450 B.C.), and from Ezra until the destruction of the Temple in 70 A.D. five more were prepared, for a total of seven (3:5).

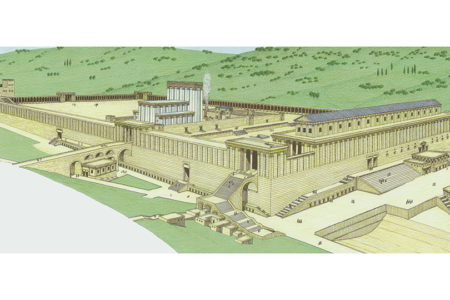

- Apparently a jar with the ashes of the previous heifers was kept in the “House of Stone” which was near the Eastern Gate of the Temple compound (3:1, 3).

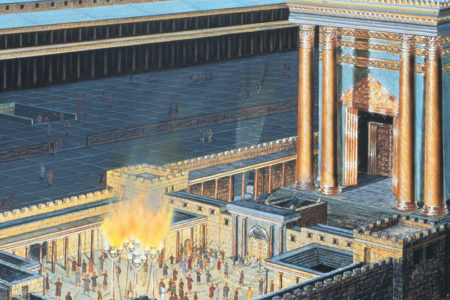

- A special causeway was built from the Eastern Gate to the Mount of Olives for use by the priest and the heifer during the ritual (3:6).

- On a particular spot on the Mount of Olives the priest immersed himself, killed the heifer, sprinkled the blood toward the Temple, and burned the heifer with the appropriate cedar wood, hyssop, and scarlet wool (3:6–10).

- The cinders were then beaten and sifted, and the ashes were placed in a jar (Heb., kalal) and kept for future rituals (3:11).

- The rest of the tractate describes the elaborate ways in which the ashes, mixed with water, were used to cleanse various types of ritual defilement.

There were no heifers sacrificed after the destruction of the Temple in 70 A.D. There is strong evidence, however, that the ashes were still used. “As late as the Amoraic period (200–500 A.D.) those who had become ritually unclean through contact with the dead still used to cleanse themselves with it.”2 This important fact should be remembered and will be referred to later in this article.

The rabbis labored long and hard to resolve the perplexing paradoxes associated with this ordinance. They finally concluded that it was the classic example of a statute for which no rational explanation can be adduced but which must be observed because it is divinely commanded.3 One homiletical application explained that the ritual was to atone for the sin of the golden calf. In other words, the mother (i.e., the cow) would purify the defilement of the Israelites caused by her offspring (i.e., the calf).4 The section from Numbers 19 is also one of four special Sabbath readings in the synagogue prior to Passover each year.

The Red Heifer in the News

Most people are probably unaware that the hero of the fictional film “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” Indiana Jones, has a real-life counterpart. George Lucas got the idea for his treasure-hunting yarn from the work of Vendyl Jones, who believes that the ashes of the red heifer are stored in a jar buried in a cave near Qumran, site of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls from 190 to 1952. Jones has been digging in a cave in that area for more than eight years but has yet to find his bounty. He believes that when he does discover the jar (kalal) with the ashes, it will open the way for the Jewish religious authorities to renew sacrifices on the Temple Mount, either in a rebuilt Temple or a temporary Tabernacle on the site.

On what authority is Vendyl Jones basing his elaborate and expensive excavation? His source is the Copper Scroll, found in a cave in the Qumran area in 1952. When finally opened (by sawing it in strips) and deciphered, it was discovered that the Copper Scroll contained a list of over 60 sites between Jerusalem and the Dead Sea where various caches of precious metals and sacred vessels are to be found. Jones believes that the ashes of the red heifer are buried in the cave where he has been working. He also believes that with their discovery (1) both the Sanhedrin Court and the Levitical priesthood will be purified and restored; (2) the lost Ark of the Covenant will be found; and (3) the original Tabernacle of Moses twill be discovered and will function as the Tribulation Temple.5

Since Mr. Jones’ dig in a wilderness cave has enlisted a measure of cooperation from some in the Israeli archaeological community, his search has an aura of authority about it. Shlomo Goren, one of Israel’s former chief rabbis, has also lent encouragement. Others are attracted by the mystical and sensational possibilities attached to such a discovery. Is there any solid basis, however, for concluding that Mr. Jones is close to one of the greatest archaeological discoveries ever made?

A sober evaluation should cause us to be very cautious. Jones is basing almost all of his ideas on the accuracy of the Copper Scroll. The world of scholars, however, has seriously doubted the reliability of the Copper Scroll. Many scholars have actually concluded that the scroll is a hoax invented by a first-century “scribe.”6 Others have concluded that it is an example of one of many pious traditions about buried treasure from Solomon’s Temple that circulated during the Second Temple period. The official translator of the Copper Scroll made this conclusion about its authenticity: “It goes almost without saying that the document is not an historical record of actual treasures buried in antiquity. The characteristics of the document itself, not to mention the fabulous quantity of precious metal recorded in it, place it firmly in the genre of folklore. The Copper Document is best understood as a summary of popular traditions circulating among the folk of Judea, put down by a semi-literate scribe.”7

Furthermore, granting, for the sake of argument, the truth of the scroll’s statements, from where could this treasure have come? When totaled, the amount is over 200 tons of silver and gold. Certainly such fabulous wealth was beyond the means of the Essenes, the ascetic group responsible for the Dead Sea Scrolls. Jones believes, however, that the treasures are those of the Second Temple, spirited away by the Essenes for safekeeping before the Temple’s destruction.8 But this idea has serious problems. First, the Essenes (i.e., the community that evidently produced the scroll) had nothing to do with the Temple. They considered the Temple hierarchy corrupt and even produced another document, called the Temple Scroll, which embodied their vision of what a pure Temple should be like.9 Why would the Essenes want to rescue treasures and vessels from the Temple that they despised? Second, how could they ever succeed in taking away these vessels and treasures, since the Temple sacrifices continued right up to its destruction? Third, the historian Josephus, who was an eyewitness of the war, gives us no evidence that anyone rescued Temple treasures during the siege of 69 to 70 A.D. On the contrary, he stated that the treasures were still in the Temple when it was destroyed. “They [the Romans] burned also the treasury chambers, which contained huge sums of money, vast quantities of raiment, and other precious belongings; here, in fact, was the general depository of Jewish wealth, where the rich had brought the contents of their dismantled homes for safe keeping.”10 If the Essenes had no interest in the Temple, and the treasures were not rescued before its destruction, what are the fabulous treasures described in the Copper Scroll? The most probable answer is that there was no treasure at-all. One confirmation of this theory is that no trace of treasure has ever been recovered from any of the 60 sites.

But there is a further problem with Jones’ reading of the Copper Scroll. Only two published translations have been made of the Copper Scroll,11 and neither agrees with Jones’ reading of it. Furthermore, the ashes of the red heifer are not even mentioned in the scroll. In item 26, the original author states that in the “Cave of the Column” is buried a “jar” (kalal). This is the same word that is used in the Mishna for the container that carried the ashes of the red heifer. On the basis of this usage, Jones concludes that the document is describing the hiding place of the jar of ashes. It is possible, however, that this word in Mishnaic Hebrew was used to describe any ceremonial jar, not just the one for the ashes.12 In any case, the Copper Scroll clearly states what the contents of the kalal are—a scroll, not ashes. Allegro’s translation is as follows: In the inner chamber of the platform (or the ‘cave of the column’) of the Double Gate, facing east in the northern entrance, buried at three cubits, there is a pitcher, in it, a scroll, under it 42 talents.”13 Nothing is said about ashes. If the kalal mentioned in the scroll contained such a valuable commodity, it is strange that the author did not mention it. At this point, it is also important to remind ourselves of the point made earlier: During the Amoraic period (ca. 200–500 A.D.) the ashes were still used to purify those who had come into contact with the dead. If, as Jones believes, the ashes were buried in a Qumran cave before 70 A.D., how could they have been used hundreds of years later?

The idea that it is necessary to find the ashes before Temple sacrifices can be renewed is the motivation for the searchers. Although some Jewish writers acknowledge this problem, it has never been one that has prevented other preparations for renewing the Temple services, if the opportunity should arise. This writer’s personal opinion is that the rabbis could simply decide to kill a red cow and use its ashes without having the previous ashes. This was confirmed by a recent visit to the Temple Institute in Jerusalem, where an enthusiastic group of religious Jews are busily preparing ritual vessels, objects, and garments for use in a rebuilt Temple. Upon inquiring about the necessity of finding the ashes before a new heifer could be killed, a spokesman informed me that Jewish law did not teach that it is necessary to find the ashes. When they find a red cow, and the opportunity arises, they can kill the cow and use its ashes without mixing them with the old ashes. In any regard, this is a problem related to Jewish law, not a problem that has to be solved by Christians.

Whatever the truth about the treasures of the Copper Scroll, the effort to base a theology and an archaeological expedition on such a sensational and groundless theory is, at best, shaky and, at worst, rather foolhardy. To conclude that Mr. Jones will never find the ashes of the red heifer is beyond the ability of anyone to say, given the limited amount of information available. It is doubtful, however, that he is on track, inasmuch as he is basing his entire endeavor on an obscure interpretation of an even more obscure document.

The Red Heifer and the Messiah

The ordinance of the red heifer has played a significant role in Jewish tradition. The author of the Epistle to the Hebrews also mentions the red heifer ritual:

For if the blood of bulls and of goats, and the ashes of an heifer sprinkling the unclean, sanctifieth to the purifying of the flesh, How much more shall the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without spot to God, purge your conscience from dead works to serve the living God? (Heb. 9:13–14).

The argument is that of the lesser to the greater. If the ashes ritually cleansed outwardly (i.e., the flesh), in a far better way the blood of Christ cleanses inwardly (i.e., the conscience).

The lasting truth conveyed by this ancient ordinance concerns the Messiah’s redemptive work which, having been done, never needs to be repeated (cp. Heb. 10:11–12). With this New Testament perspective in mind, I leave the reader with an important question: Are you looking for the ashes, or are you looking for Christ?

ENDNOTE

- Ecclesiastes Rabbah 7:23.

- Encyclopedia Judaica, vol. XIV, 12.

- Numbers Rabbah 19:8.

- Pesikta Rabbati 14:65a.

- Israel at Forty, Harold Willmington and Ray Pritz, Tyndale House, 1988, 80-81; “Seekers of the Lost Ark,” Jerusalem Post, June 10, 1989, 8b; also see the various “Research Letters” published by Institute of Judaic-Christian Research, PO Box 120366, Arlington, TX 76012. Mr. Gary Collett is also digging in another cave in the Qumran area, basing his ideas on the same arguments as Vendyl Jones. Mr. Collett believes that the discovery of the ashes will lead to “world revival,” and agenda which Mr. Jones rejects.

- See T H. Gaster, The Dead Sea Scriptures, 3rd. ed. (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1976), 533-536.

- J. T. Milik, “The Copper Document from Cave III, Qumran,” Biblical Archaeologist, vol. XIX, 3, 1957, 63.

- A variation on this theme is the view of John Allegro, who concluded that the Zealots “rescued” the treasures in AD 68, before the Romans arrived, and deposited them for possible use in the coming war. See J. M. Allegro, The Treasure of the Copper Scroll (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1960).

- Yigael Yadin, The Temple Scroll (Jerusalem: Steimatzky Ltd., 1985).

- The Jewish War, ed. By Gaalyah Cornfeld (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing Co., 1982), 424.

- Allegro (see endnote 8) and J. T. Milik in Discoveries in the Judean Desert, III (New York, NY: Oxford Press, 1963).

- Marcus Justrow, Dictionary of the Targumim, Talmud Babli, Yerushalmi, and Midrashic Literature (New York, NY: Judaica Press, 1982), 1377.

- Allegro, 43.

Very interesting, this is all needed by the Jewish people. But thank God we have the

Blood of our Savior.

Good information! Thank you.

Why all the confusion and doubt? Jesus will straighten it all out when He comes!!