‘Jerusalem of Gold’

A Special Song for a Special Time

Few songs have epitomized the soulful pull of Jerusalem better than Naomi Shemer’s “Jerusalem of Gold.”

Its debut at the Israel Song Festival was broadcast live on the country’s 19th Independence Day, May 15, 1967, from Jerusalem’s national convention center.

Known in Hebrew as Yerushalayim Shel Zahav, the song had been composed at the urging of Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek, according to writer Yael Levine on jerusalemofgold.co.il.

Although many poems and songs had a Jerusalem theme, Kollek and the festival organizers felt few were dedicated to Jerusalem and to the Old City in particular.

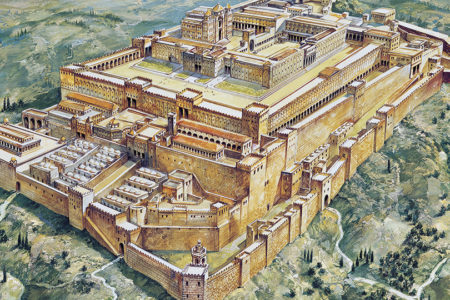

Perhaps it was too painful to compose music about Jerusalem after 1949 because the city was still divided. Jewish people were barred from the Jordanian side, where their holiest sites—the Temple Mount, Western Wall, and Mount Zion—were situated.

Asked to “write on demand” about Jerusalem, Shemer and her fellow festival songwriters recoiled. Was it collective writers’ block? She told festival director Gil Aldema she simply could not do it.

Write whatever you want, he told her.

“That very night,” wrote Levine, “‘Jerusalem of Gold’ was born.” The lyrics drew upon Shemer’s personal memories.

Though born on July 13, 1930, at Kvutzat Kinneret, a kibbutz on the Sea of Galilee, she had studied at Jerusalem’s Rubin Academy of Music. She often spent time in the summer in Jerusalem and had given birth to her daughter there.

The phrase Jerusalem of Gold was not something Shemer ever claimed authorship over.

In its first incarnation, Shemer’s song was almost terse.

What was missing, her friend, performer Rivka Michaeli, said after she heard it for the first time, was a reference to the Old City.

The Old City was implied, Shemer responded, in the line “And in her heart a wall” (Uvelibah chomah).

That didn’t cut it, said Michaeli, whose father was born in the Old City and had been exiled from it for 19 years, wrote Levine.

Shemer then composed a second stanza that lamented the Old City’s empty marketplaces, lack of pilgrims on the Temple Mount, and absence of sojourners heading down from Jerusalem to the Dead Sea along the Jericho road.

She later explained this stanza wasn’t merely about the 19 years of Jordanian occupation and Jewish exclusion. It was a lamentation over the loss of sovereignty that had lasted two millennia, since the destruction of the second Temple and Rome’s expulsion of the Jewish people in AD 70.

When “Jerusalem of Gold” was first performed publicly, Arab armies were massing. Neighboring leaders were baying for Jewish blood. In a matter of days, Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser expelled UN peacekeepers, began moving his troops into the Sinai, and closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping. Cairo Radio declared, “The existence of Israel has continued too long.”

Meanwhile, “Jerusalem of Gold” reverberated. It catapulted to fame not due to 37-year-old Naomi Shemer but to a 20-year-old female soldier named Shuli Natan.

Shemer had heard Natan perform on a radio program featuring new talent. It struck her that her song and Natan’s voice were perfectly matched. The Song Festival producers hesitated to put the unknown Natan on stage, but Shemer insisted. Natan herself was full of trepidation.

In the end, Natan’s rendition profoundly touched the convention hall audience and radio listeners around the country as few other songs had. Hearts melted.

Before people could learn much about Natan, who had been born in London and immigrated to Israel with her family in 1949, the Six-Day War broke out on Monday, June 5, 1967.

Then, on June 7, the Israeli army liberated Jerusalem’s Old City.

Shemer and Natan were entertaining troops in the Sinai Peninsula when they heard the remarkable news. It was in El-Arish that Shemer composed the third and final stanza of the song.

Shemer wrote and set hundreds of poems and prayers to music and composed music for poems written by the Israeli poetess Rachel and others who had a love for the land of Israel.

Having captured the hearts of millions of Israelis and friends of Israel worldwide, she went on to win the Israel Prize in 1987.

When she died at age 74 on June 26, 2004, in Tel Aviv—the city that had become her home—many on the political left took the opportunity to point out the melody of “Jerusalem of Gold” borrowed heavily from Basque folk music.

But as author, essayist, and biographer Hillel Halkin pointed out, the traditional Hanukkah tune Ma’oz Tsur sounds a lot like a German hymn; and Israel’s national anthem, Hatikva, plainly has its melodic roots in Bedrich Smetana’s “Moldau,” a Romanian folk song. So what if “Jerusalem of Gold” has a Basque doublet?

Shemer’s music speaks to those who are willing to allow Zionist idealism into their hearts, just as it grates on those who cannot.

As for Shuli Natan, she is still performing. To watch her sing “Jerusalem of Gold” on YouTube, go to tinyurl.com/shuliJOG. And for the English translation of the Hebrew lyrics, click here.