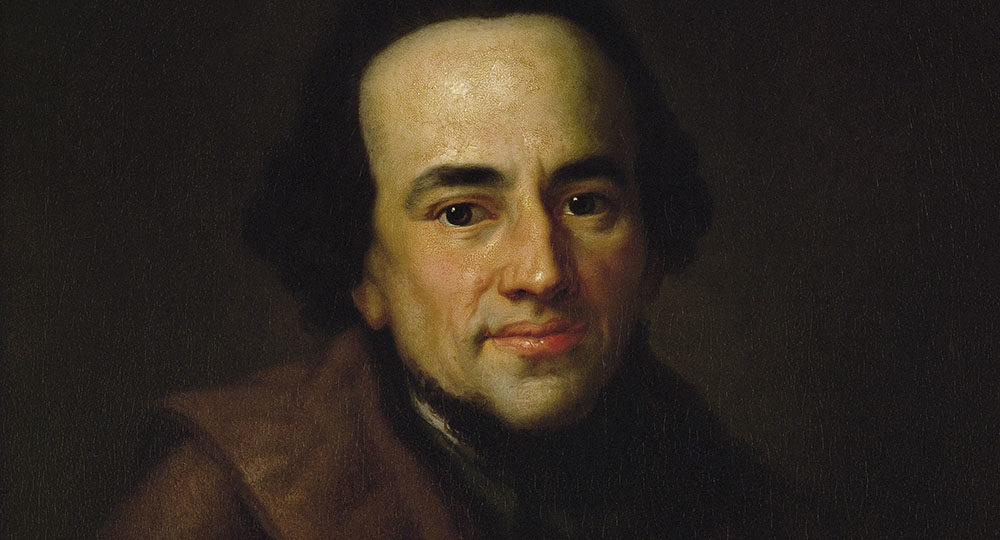

Moses Mendelssohn

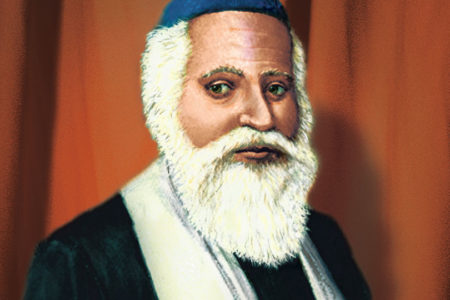

Nine years after the Vilna Gaon’s birth in Lithuania, another man was born whose influence opened the door to assimilation. He is known as the father of the Jewish Enlightenment, the Haskalah, which eventually helped birth the Reform and Zionist movements.

Moses Mendelssohn was born in Germany on September 6, 1729, the son of Torah scribe Mendel of Dessau.1 A contemporary of the Vilna Gaon, his life and education were far different. Although an Orthodox Jew his entire life, Mendelssohn sought to expose the Orthodox community to modern teaching and secular concepts.

Forced to live in urban ghettos (the first was established in Venice in 1517) or in small villages called shtetls, the Jewish people were isolated from their Gentile neighbors. They studied only Torah and Talmud, spoke only Yiddish, and paid little or no attention to what was transpiring outside their world. Mendelssohn believed the only way to end their segregation was to open their minds to non-Jewish thought.2 Those who followed this philosophy believed Western wisdom and scholarship were the keys to entering non-Jewish society.3 Thus began the Haskalah, from the Hebrew word sechel, meaning “reason” or “intellect.”4

Although Mendelssohn faithfully studied Torah, Talmud, and learned the writings and thoughts of the great Rabbi Moses ben Maimon (Maimonides, 1135–1204), he also became proficient in German literature and philosophy. In fact, German intellectuals respectfully called him the “Jewish Socrates.”5

In 1783 Mendelssohn translated the entire Torah and the book of Psalms into German, using Hebrew letters. Ironically, his descendants, including his famous grandson, composer Felix Mendelssohn, left Judaism for Christianity.6

Felix was, in fact, a committed Christian. When he died in 1847, a 600-voice choir sang “Christ and the Resurrection” at his funeral. He is buried in Holy Cross Church Cemetery in Berlin, where a huge cross marks his grave.7

Felix’s Christianity, however, meant nothing to the Nazis. Wrote Rabbi Samuel M. Stahl:

To them, he was always a Jew. Almost a century after his death, they besmirched his memory as a Jewish composer. They forbade his music to be played. They ordered that the huge statue of him in Leipzig be taken down and destroyed. They also closed the Mendelssohn banking house and ordered all the Mendelssohn descendants still living in Germany to leave the country.8

ENDNOTES

- Solomon Grayzel, A History of the Jews (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1977), 542.

- Abba Eban, Heritage Civilization and the Jews (New York: Summit Books, 1984), 225.

- Ibid.

- Shira Shoenberg, “The Haskalah” <www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/Haskalah.html>.

- William C. Varner, “Syllabus; Jewish History From the First Century to the Present” (Bellmawr, NJ: Institute of Biblical Studies, photocopy, n.d.), 29.

- Shira Shoenenberg, “Moses Mendelssohn” <www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Mendelssohn.html>.

- Rabbi Samuel M. Stahl, “Felix Mendelssohn: Musical Genius and Jewish Casualty” <www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Mendelssohn2.html>.

- Ibid.