The Altar of Sacrifice

Most people today are familiar with the concept of blessing. But they know little about the idea of sacrifice, particularly on an altar. Yet the altar was an important part of Israelite worship.

When God instructed Moses to build the Tabernacle in the wilderness, He told him how to make a place for sacrifice: “An altar of earth [natural materials, including stone]1 you shall make for Me, and you shall sacrifice on it your burnt offerings and your peace offerings, your sheep and your oxen. In every place where I record My name I will come to you, and I will bless you” (Ex. 20:24).

The concept of the altar (Hebrew, mizbeah) goes back to the Garden of Eden. Adam presumably constructed the first one based on the example of God’s sacrifice of an animal to clothe Adam and Eve (Gen. 3:21). Adam obviously taught his sons Cain and Abel to build a sacrificial altar (4:3–4); and we see this act of obedience followed by Noah (8:20), the Patriarchs (12:7; 26:25; 35:7), Moses (Ex. 17:15), Joshua (Josh. 8:30), and the Israelites (Dt. 12:1, 5–6).

Throughout this period, the kings of Israel were responsible for the construction and maintenance of legitimate altars for the God of Israel and the destruction of altars dedicated to other gods.2 This practice continued until the destruction of the first Temple. It then resumed until the destruction of the second Temple in AD 70 when the sacrificial system was forced to end.

The altar of sacrifice stood outside, in the Tabernacle’s forecourt (Ex. 27:1–8; 38:1–7), and was called “the altar of burnt offering” (ha mizbeah, ha ollah). There the Israelites offered regular sacrifices for atonement. But the altar of incense stood inside (30:1–10; 37:25).

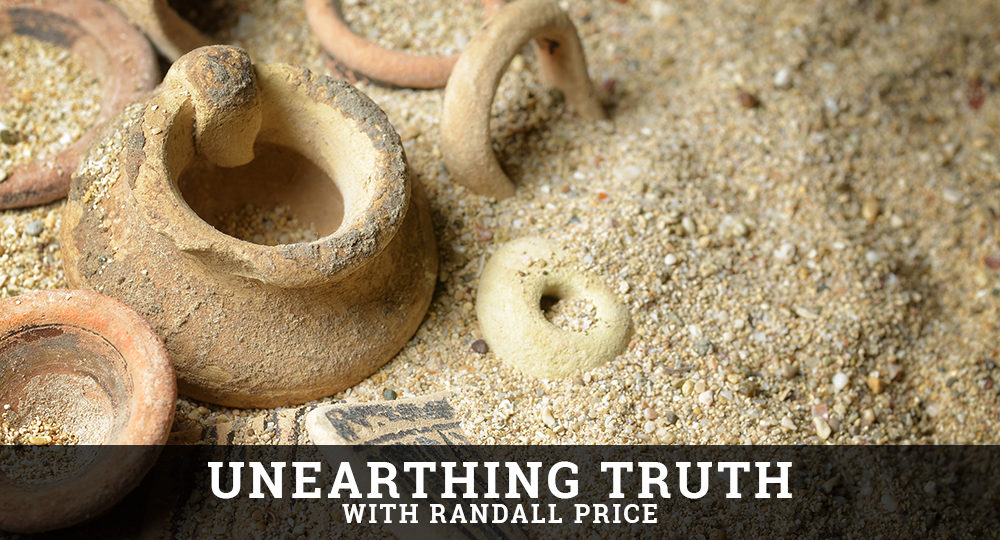

The sacrificial altar, built of acacia wood, was overlaid with bronze and therefore called the brazen altar. It was hollow but probably filled with earth to dissipate the heat generated by the burning sacrifices. Several archaeological examples exist of altars constructed with a fill of ash or earth/rubble. A bronze grating formed the altar’s “floor,” where the wood was placed. It may have functioned like a modern barbeque grill in letting in air to facilitate cooking.

A unique design feature of these altars was “horns”—stone projections from the corners—that apparently aided in binding a living sacrifice to the structure (Ps. 118:27; cf. Rom. 12:1).

Priests had to ascend the altar because wood was placed on top of it and the sacrifice was then placed on the wood. However, God commanded that the altar could not be mounted by steps because this was a pagan practice associated with priests exposing themselves as part of fertility rituals (Ex. 20:26).3 A large, circular, stone Canaanite altar unearthed at Megiddo fits the pagan scenario.

To avoid anything associated with pagan beliefs, Israelite altars were built with ramps, beginning with the one in the Tabernacle. Also, since the Tabernacle’s altar had to be portable, it was also equipped with rings through which poles could be inserted for transport.

The archaeological evidence for altars in Israel is quite extensive. One of the most impressive from the time of the Tabernacle is located on Mount Ebal and has been identified as the altar described in Joshua 8:30–35. It measures 27 feet by 21 feet and is preserved to a height of 10 feet, with a ramp 3.5 feet wide. It was surrounded by an inner courtyard that contained ash, animal bones, and clay vessels filled with ash and bones.

The sacrificial altar reminds us that our sin requires a sacrificial substitute so that we may obtain forgiveness from God and that Jesus came to fulfill this great purpose (Isa. 53:5–6, 10).

ENDNOTES

-

-

- Where altars of stone (mizbeah. ’ăbānîm) are specified, it was forbidden to use iron tools to shape the stones (Ex. 20:25; Dt. 27:5–6; Josh. 8:31).

- See N. H. Gadegaard, “On the So-Called Burnt Offering Altar in the Old Testament,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 110 (1978): 35–45.

- Jewish priests also were required to wear undergarments (Ex. 28:42–43; Lev. 6:10), which pagan priests did not do.

-