The Ancient Sopherim

From the ancient world to today, scribes (Hebrew, sopherim) have played a crucial role in preserving Jewish culture. Other ancient civilizations also had scribes. But Israel’s were unique.

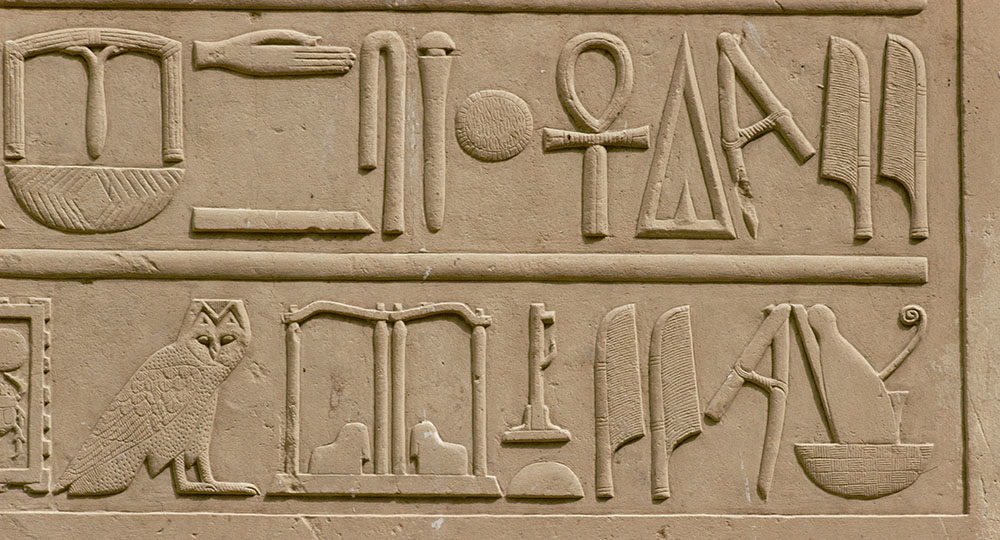

In ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, only the scribes could read and write. Egyptian hieroglyphs and the cuneiform writing of Mesopotamia were difficult and complex. In God’s providence, the time of the Exodus from Egypt was the very time the simple 22-letter alphabet began to be used. Suddenly, anyone could read and write. Israel was unique, however, because every man was not only able to read, he was commanded to read. Consequently, the role of the scribe was different in Israelite society, where everyone could read and write.

The Israelite scribe was first and foremost a faithful witness; he wrote exactly what he heard, and he copied any writing exactly as it was given to him. Some scribes served as notaries, placing their seals on documents to verify their authenticity. On display in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem is a clay fragment bearing the seal of Baruch the son of Neriah, the scribe who preserved in writing the words of Jeremiah the prophet. A scribe’s highest calling was to copy, precisely and without error, the words of the Bible.

Scribes were required to be expert in every aspect of their work. Every scribe knew how to manufacture the tools of his profession. He was able to turn animal skins, usually sheepskins or deerskins, into fine leather surfaces that would absorb ink and retain the shapes of letters for hundreds of years. He made his ink from gallnuts, little round bulges that form on oak trees when certain insects lay their eggs. These gallnuts contain tannin, a basic ingredient of ink. His pen was a quill with the tip cut at a precise angle and length.

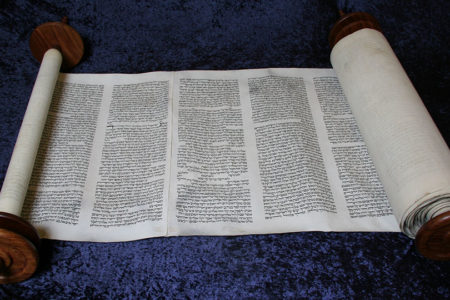

Our English word scribe comes from the final step in the preparation of a scroll. The sopherim needed lines on the writing surface to guarantee the letters would be uniform in size and the columns uniform in width. In English, we write on top of the line. Hebrew letters are written suspended below the line; that is why so many Hebrew letters have a thick bar across the top. On a Torah scroll, these lines could not be drawn with ink because only the words of God could be written with the permanence of that medium. So a sopher would use a thorn and ruler to “scribe” lines into the leather’s surface. As a scroll aged, these lines became more visible; they can be seen clearly on many pages of the Vilna Scroll, which is 300 years old.

Over the years, the Jewish scribes developed rigorous stipulations for writing biblical scrolls. The Talmud contains an entire tractate, almost an individual book, devoted to the rules for the work of the scribes. There are rules for the writing materials, the size and dimensions of the scrolls, and the size of the columns and lines. Another Talmudic tractate stipulates that each column should be wide enough to write the longest word in the Hebrew Bible (lemishpachoteycem, “for your families”) three times. Torah scrolls are written in paragraphs, with specific rules governing whether a paragraph can begin on the same line or must begin on a new line. Each book of the Torah must be separated from the previous book by four lines. The rules for writing each letter and each word are equally meticulous.

From A.D. 600 to A.D. 1000 a special group of scribes called Masoretes dedicated themselves to preserving the exact pronunciation of each word of the Bible. Scrolls used in synagogues contain no vowels. So the Masoretes developed a system of vowel pointing, called nikud, and accent marks to insure the Bible would be read aloud accurately. Today Jewish people around the world use the Masoretic texts when studying the Hebrew Scriptures and teaching boys how to read the Bible aloud on the day of their bar mitzvah.

As Christians, we owe a great debt to the ancient sopherim, whose meticulous work over the millennia has preserved for us the Hebrew Scriptures we read today.