The Conquest Over Pagan Jericho

When people hear the word Jericho, they naturally think of Israelites marching, trumpets sounding, and walls falling down. It is a wonderful story of faith and victory that we enjoy reading and telling in Sunday school class, but did it really happen? The skeptic would say no; it is merely a folk tale to explain the ruins at Jericho. A careful examination of the archaeological evidence collected throughout the last century, however, leads to another conclusion.

The name Jericho most likely derives from the root yrh—moon—suggesting that the residents of the area were originally moon worshipers. Canaanite texts from Ugarit (see Bruce Scott’s article for a fuller description) refer to a moon deity named yrh. No matter what particular gods were venerated at Jericho, it is certain that the residents were idolaters who followed the fertility and occult practices outlined in Leviticus 18; 20; and Deuteronomy 18:9–13. The people of Jericho and the other cities of Canaan, and even the land itself, had become defiled by the idol worship, so the Canaanites were to be destroyed, subdued, and driven out (Ex. 23:20–33; Lev. 18:24–28; 20:23; Dt. 18:12; 20:16–18; 31:3–5).

Fortification of Jericho

Before the Israelites entered the promised land, Moses told them, “Thou art to pass over the Jordan this day, to go in to possess nations greater and mightier than thyself, cities great and fortified up to heaven” (Dt. 9:1). The meticulous work of British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon in the 1950s showed that Jericho was indeed heavily fortified and that it had been burned by fire. Unfortunately, she misdated her finds, resulting in what seemed to be a discrepancy between the discoveries of archaeology and the Bible. She concluded that the Bronze Age city of Jericho was destroyed in 1550 B.C. by the Egyptians. An in-depth analysis of the evidence, however, reveals that the destruction took place at the end of the 15th century B.C., exactly when the Bible says the conquest occurred (Bryant G. Wood, “Did the Israelites Conquer Jericho?” Biblical Archaeology Review, March/April 1990, pp. 44–58).

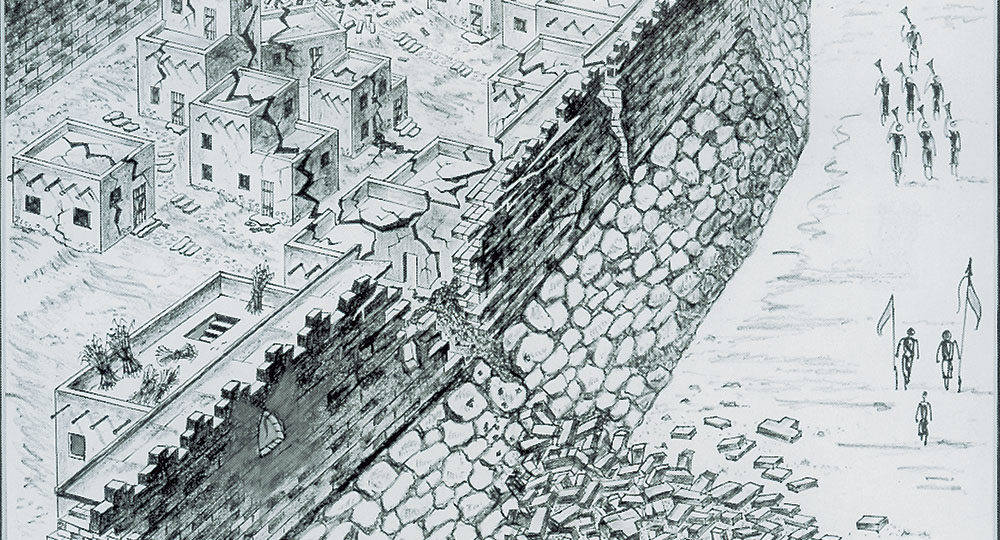

The mound, or tell, of Jericho was surrounded by a great earthen rampart or embankment with a stone retaining wall at its base. The retaining wall was approximately 12 to 15 feet high. On top of it was a mud-brick wall six feet thick and about 20 to 26 feet high (Ernst Sellin and Carl Watzkinger, Jericho die Ergebusisser der Ausgrabungen, p. 58). At the crest of the embankment was a similar mud-brick wall whose base was roughly 46 feet above ground level outside the retaining wall. This wall loomed above the Israelites as they marched around the city each day for seven days. Humanly speaking, it was impossible for the Israelites to penetrate the impregnable bastion of Jericho.

The account of the spies going to Jericho in Joshua 2 mentions a city gate (vv. 5, 7). Thus far, no trace of a gate has been found. It most likely would have been on the eastern side of the city to give access to the Jordan valley, where the main travel route was located and also where the agricultural fields were situated. Unfortunately, the entire east side of the tell has been destroyed by a modern road, a reservoir to contain the waters of the Ain es-Sultan (Spring of Elisha in Arabic, see 2 Ki. 2:19–22), and agricultural fields.

Within the upper wall was an area of approximately six acres, while the total area of the upper city and fortification system was half again as large—about nine acres. Based on the archaeologist’s rule of thumb of 200 people per acre, the population of the upper city would have been about 1,200. From excavations carried out by a German team in the first decade of this century, however, we know that people were also living on the embankment between the upper and lower city walls. In addition, those Canaanites living in surrounding villages would have fled to Jericho for safety. Thus, we can assume that there were several thousand people inside the walls when the Israelites came against the city.

The Fallen Walls

The citizens of Jericho were well prepared for a siege. A copious spring that provided water for ancient as well as modern Jericho lay inside the city walls. At the time of the attack, the harvest had just been taken in Josh. 3:15), so the citizens had an abundant food supply. This is evident by the many large jars full of grain found in the Canaanite homes by John Garstang in his excavation in the 1930s and also by Kenyon. With a plentiful food supply and ample water, the inhabitants of Jericho could have held out for several years.

After the seventh trip around the city on the seventh day, Scripture tells us that the wall “fell down flat” (Josh. 6:20). A more accurate rendering of the Hebrew here would be “fell beneath itself.” There is ample evidence that the mudbrick city walls collapsed and were deposited at the base of the stone retaining wall at the time the city met its end. The German expedition excavated a number of points adjacent to the retaining wall. In each case, they found a pile of collapsed mud bricks.

Kenyon’s work at Jericho was the most detailed excavation. On the west side of the tell, at the base of the retaining or revetment wall, she found “fallen red bricks piling nearly to the top of the revetment. These probably came from the wall on the summit of the bank” and/or “the brickwork above the revetment” (Kathleen M. Kenyon, Excavations at Jericho, vol. 3, p. 110). In other words, she found a heap of bricks from the fallen city walls. An Italian team excavating at the southern end of the mound in 1997 found exactly the same thing.

According to the Bible, Rahab’s house was incorporated into the fortification system Josh. 2:15). If the walls fell, how was her house spared? As you will recall, the spies had instructed Rahab to bring her family into her house and they would be rescued. When the Israelites stormed the city, Rahab and her family were saved as promised Josh. 6:17, 22–23).

At the north end of the tell of Jericho, archaeologists made some astounding discoveries that seem to relate to Rahab. The German excavation of 1907–1909 found that on the north, a short stretch of the lower city wall did not fall, as it did everywhere else. A portion of that mud-brick wall was still standing to a height of eight feet (Sellin and Watzkinger, p. 58). Also, there were houses built against the wall. It is quite possible that this is where Rahab’s house was located. Because the back walls of the houses were, in fact, the city wall, the spies could have readily escaped. From this location on the north side of the city, it was only a short distance to the hills of the Judean wilderness, where the spies hid for three days (Josh. 2:16, 22). Real estate values must have been low here, inasmuch as the houses were positioned on the embankment between the upper and lower city walls—not the best place to live in time of war! This area was, no doubt, the overflow from the upper city and the poor part of town, perhaps even a slum district.

After the city walls fell, how did the Israelites surmount the 12- to 15 foot-high retaining wall at the base of the tell? Excavations have shown that the bricks from the collapsed walls formed a ramp against the retaining wall, so the Israelites simply climbed up over the top. The Bible is very precise in its description of how the Israelites entered the city: “the people shall ascend up, every man straight before him” Josh. 6:5). The Israelites had to go up, and that is what archaeology has revealed. They had to go from ground level at the base of the tell to the top of the rampart in order to enter the city.

Destruction by Fire

The Israelites “burned the city with fire, and all that was in it” Josh. 6:24). Once again, the discoveries of archaeology have verified the truth of this record. A portion of the city destroyed by the Israelites was excavated on the east side of the tell. Wherever the archaeologists reached this level, they found a layer of burned ash and debris about three feet thick. Kenyon described the massive devastation as follows:

“The destruction was complete. Walls and floors were blackened or reddened by fire, and every room was filled with fallen bricks, timbers, and household utensils; in most rooms the fallen debris was heavily burnt, but the collapse of the walls of the eastern rooms seems to have taken place before they were affected by the fire” (Kenyon, p. 370).

It was in this area that both Garstang and Kenyon found many storage jars full of grain that had been caught in the fire destruction. This is a unique find in the annals of archaeology. Grain was valuable, not only as a source of food, but also as a commodity that could be bartered. Under normal circumstances, valuables such as grain would have been plundered by the conquerors. Why was the grain left to be burned? The Bible provides the answer. Joshua commanded the Israelites, “And the city shall be accursed, even it, and all that are in it, to the Lord; only Rahab, the harlot, shall live, she and all who are with her in the house, because she hid the messengers that we sent. And ye, in every way keep yourselves from the accursed thing, lest ye make yourselves accursed, when ye take of the accursed thing, and make the camp of Israel a curse, and trouble it. But all the silver, and gold, and vessels of bronze and iron, are consecrated unto the Lord; they shall come into the treasury of the Lord” Josh. 6:17–19).

The grain left at Jericho and found by archaeologists in modern times gives graphic testimony to the obedience of the Israelites nearly three and a half millennia ago. Only Achan disobeyed, leading to the debacle at Ai, as described in Joshua 7.

Such a large quantity of grain left untouched gives silent testimony to the truth of yet another aspect of the biblical account. A heavily fortified city with an abundant supply of food and water would normally take many months, even years, to subdue. The Bible says that Jericho fell after only seven days. The jars found in the ruins were full, offering proof that the siege was short because the people inside the walls had not yet consumed their stores of the grain.

Lessons of Jericho

Jericho was once thought to be a “Bible problem” because of the seeming disagreement between the evidence of archaeology and the biblical record. Once the archaeology is correctly interpreted, however, just the opposite is the case. The archaeological evidence supports the historical accuracy of the biblical account in every detail. Every aspect of the story that could possibly be verified by the findings of archaeology is, in fact, verified.

There are many ideas as to how the walls of Jericho came down. Both Garstang and Kenyon found evidence of earthquake activity at the time the city met its end. If God did use an earthquake to accomplish His purposes that day, it was still a miracle, in that it happened at precisely the right moment and was manifested in such a way as to protect Rahab’s house. No matter what agency God used, it was ultimately the faith of the Israelites that brought the walls down: “By faith the walls of Jericho fell down, after they were compassed about seven days” (Heb. 11:30).

The example of Jericho is a wonderful spiritual lesson for God’s people today. There are times when we find ourselves facing enormous walls that are impossible to break down by human strength. If we put our faith in God and follow His commandments, even when they seem foolish to us, He will perform great and awesome deeds (see Dt. 4:34) and give us His victory.

Editor’s Note: Dr. Bryant G. Wood is an internationally recognized authority on the archaeology of Jericho. He is director of the Associates for Biblical Research and is also director of the Kh. El-Maqatir Excavation in Israel. For more information on archaeology and the Bible, or to go on a dig in Israel with Dr. Wood, contact the Associates for Biblical Research, 31 East Frederick St., Suite 468, Walkersville MD 21793–8232. Visit the ABR website.

nice wall