The Jewishness Of Jesus

I had never seen Michael, our Israeli guide, so excited. Our Institute of Biblical Studies group was touring the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, seeing the usual sights, when Michael motioned us to join him on the other side of the church. He led us down a corridor into a small chapel. Michael explained in hushed tones that this was a very ancient part of the church, and tourist groups usually do not get to see it.

The thing that had excited Michael about the room was a painting on the front wall depicting Jesus and His disciples with Semitic features: brownish skin, narrow faces, dark hair, and beards. Michael explained that this portrait probably was closer to how Jesus really looked than most Western art of the following 1,500 years.

It is curious that when people portray Jesus, whether in paintings or in books, it is usually done in an idealized fashion, as the perfect man of each artist’s imagination. Such a portrayal is far from the real Jesus. As modern historians now emphasize, Jesus was from Jewish lineage, was part of first-century Palestinian-Jewish culture, and interpreted His ministry as being in line with Judaism as it is understood from the Old Testament. Any other picture of Jesus is not historically valid.

Unfortunately, there are still those who seek to separate Jesus from His Jewish lineage, Jewish culture, and, especially, from Judaism as a religion. The purpose of this article is to reaffirm the Jewishness of Jesus in these three areas.

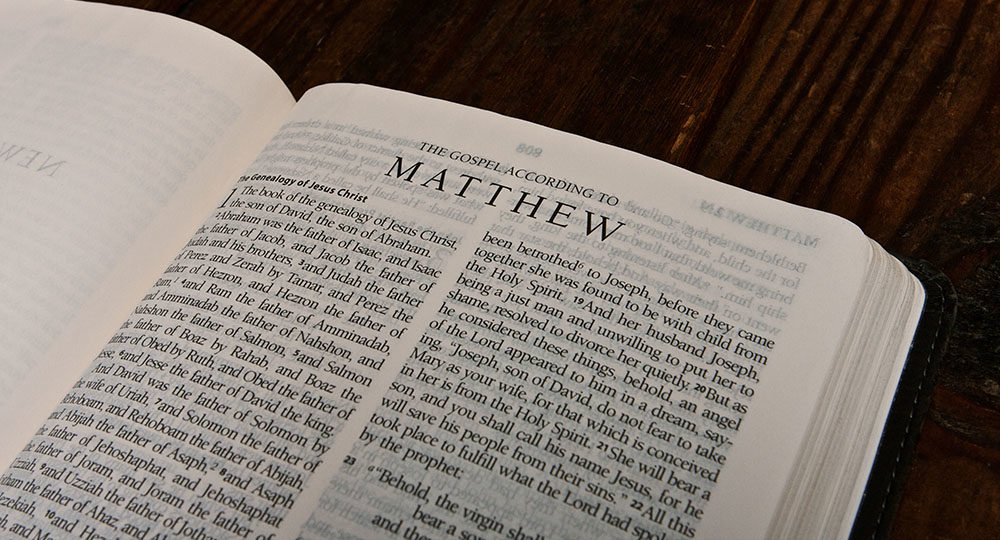

Jesus Was From Jewish Lineage

The Gospels provide two genealogies of Jesus, one in Matthew and the other in Luke. Both genealogies trace Jesus’ lineage through Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, David, and Joseph, which qualifies Jesus as a Messianic heir. As Luke wrote, when the census was taken, Joseph went to Bethlehem because “he was of the house and lineage of David” (Lk. 2:4). But since Joseph was not involved in the conception of Jesus—because Jesus was conceived by the Holy Spirit in Mary’s womb—the focus of Luke’s Gospel shifts to the lineage of Mary.

Was Mary Jewish? Many maintain that Luke gives Mary’s lineage, but this is not certain. However, there is no hint in the Gospels that Mary was anything other than Jewish. It is probable that she was from David’s blood line, for it was normal and desirable for men to marry women from the same tribe, many times to as close a relative as was allowed by law. Also, Paul, when referring to Jesus’ humanity, indicated that Jesus was descended from David (Rom. 1:3; 2 Tim. 2:8). The Gospels assume that Jesus was ethnically Jewish. There is no indication that any of His contemporaries questioned His Jewishness.

In addition, the baby Jesus, eight days after He was born, was circumcised (Lk. 2:21). This rite was the sign of the Abrahamic Covenant (Gen. 17) and meant that Jesus was then religiously considered a Jew. He was, under the provisions of the Abrahamic Covenant, a part of the community of Israel.

Jesus Was Culturally Jewish

While Jesus was critical of the way Judaism was practiced in His society, He was not a cultural revolutionary. Rather, He embraced His Jewish heritage.

Before Jesus began His preaching ministry in His early 30s, He learned and practiced the trade of His father Joseph (Mt. 13:55; Mk. 6:3). Jesus was a woodworker (Greek, tektón), one who fashions furniture, farming implements, and other common items from wood. Jesus was probably a skilled worker, and most likely “Joseph and Sons” was the sole woodworking business in a small town like Nazareth.

Since Joseph and Mary were devout Jews, displayed by their belief in the promises of God and their keeping of the commandments, it follows that Jesus most likely had a devout Jewish upbringing. This would have included the basics of the Law: keeping the Sabbath, attending the feasts in Jerusalem, and studying the Old Testament in the synagogue. Jesus excelled in His understanding of the Scriptures, as seen in the account of His confounding the Jewish teachers at the Temple in Jerusalem when He was 12 years old (Lk. 2:41–50).

Jesus’ teaching also gave proof of His Jewish background. He taught the Jewish people in a popular style that was easily understood. Witty sayings, parables, natural illustrations, and rabbinic methods of argumentation were all part of His style of communication. Naturally, Jesus based His teaching on the Old Testament, frequently quoting passages and citing characters as points in His arguments and as illustrations. In all of Jesus’ disputes with the Pharisees, He never disparaged Judaism as contrary to God’s revelation or character.

Jesus Was Religiously Jewish

We do not have to read very far in the Gospels before coming upon accounts of Jesus disputing with the Jewish religious leaders, the Pharisees. From these accounts, we can conclude that Jesus was opposed to Judaism and sought to establish a totally distinct religion. Was Jesus against Judaism?

Before we can properly answer this question, we must first define Judaism. Is Judaism to be understood ideally—in terms of what God desired from those in relationship to Him under the Abrahamic and Mosaic Covenants—or practically—in terms of the actual practice of the Jews, according to their laws, during the time Jesus lived? If Judaism is defined ideally, according to God’s desire for His people in the Covenants, then Jesus was certainly pro-Judaism. However, if Judaism is defined as the actual practice of Judaism by the Jews during the time of Jesus and, in particular, the religious leaders, Jesus was anti-Judaism. Let’s examine each of these points in turn.

Jesus Was Pro-Judaism According to God’s Promises in the Old Testament

The people to whom Jesus ministered recognized Him as a teacher of the Law, a “rabbi,” and a prophet from God (Mk. 8:28; 9:5; Mt. 21:10–11; Jn. 3:2). Jesus was religiously a Jew because He lived His life in obedience to Scripture based upon faith in God. His sole purpose in life was to do the will of God (Mt. 26:39). In many ways, Jesus is the ideal Israel, as displayed in the temptation narrative, where He was obedient to God in the wilderness, in contrast to the Israelites’ disobedience under Moses (Mt. 4:1–11).

It is also often assumed that Jesus was opposed to the Mosaic law, but the opposite is true. Jesus confirmed the validity of the Law and the prophets (Mt. 5:17–20). Jesus interpreted the Law according to God’s intention, which was based on God’s covenantal love for the Israelites. In contrast, the Pharisees twisted the Law to establish their own righteousness, although they were far from God in their hearts. Jesus wanted the Jews to live in obedience to God from the heart, as Deuteronomy 6 teaches (cf. Mk. 12:28–34). In this respect, Jesus was in line with ideal Judaism.

However, Jesus interpreted the prophetic Scriptures in two ways that were novel to His contemporaries. First, He interpreted all the prophetic promises as being fulfilled in Himself. Jesus was God’s beloved Son (Jn. 5:31–47; Mt. 11:25–27; cp. Ps. 2:7; 89:19–29; Isa. 42:1); the prophesied Messiah (Mt. 22:44; Lk. 4:18; cp. Ps. 110:1; Isa. 61:1–2); the Son of Man (Mk. 2:10; 14:62; cp. Dan. 7:13); the Suffering Servant (Lk. 22:37; Mk. 10:45; cp. Isa. 53:10–12); and, ultimately, Lord (Mk. 2:28). Jesus’ unique interpretation of the Old Testament was based on His authority, which was given to him by God the Father. Jesus’ assumption of this authority ultimately led the religious leaders to challenge His ministry.

The second aspect that was novel to His contemporaries was His view of the wider aspects of “the kingdom” (i.e., the inclusion of Gentiles with Jews, Mt. 8:5–13), a concept that is also present in the Old Testament (Isa. 2:14; 11:10; 42:1–13; 66:18–21). The novel aspect was Jesus’ teaching that the commandments of the Mosaic law, which were binding obligations under the Sinai Covenant, would no longer be applicable to this wider group of Jews and Gentiles—the church—because they would be under the New Covenant (Mk. 2:18–22; 7:1–23; Lk. 22:20). In this way, Jesus again interpreted the Old Testament according to His authority as God’s Son, in a manner that was novel to His contemporaries but was the true expression of God’s will.

Jesus Rebuked the Judaism of His Day for Its Unbelief

Jesus did not conform to the kind of Judaism being taught by the Pharisees because, to Him, their teaching misapplied the law and thereby gave a distorted view of God’s character, which was righteously displayed in the law (Mt. 9:9–13). Beyond that, the Pharisees were also hypocrites, in that they were not sincere in their devotion to God, but were using their religious authority to profit themselves (Mt. 23). As described in the Gospels, the Pharisees’ and High Priests’ anger at Jesus, which led to His crucifixion, was motivated as much by jealousy (Mk. 15:10) and political expediency (Jn. 11:45–53; 18:14) as by the capital crime of blasphemy (Mk. 14:64). Thus, just as did many of the Old Testament prophets, Jesus rebuked Israel for their unbelief in God and His Word and pronounced judgment upon them. The result of this judgment came upon Jerusalem in AD 70, when the city was destroyed by the Romans, and the expulsion of the Jews from Judea after the Bar Kokhba revolt (AD 135).

This judgment was not Jesus’ desire. His first message to the Jews was a call to repentance—calling them back to God so that they might receive His promises (Mk. 1:15). Often during His ministry, He was deeply distressed by the Jews’ unbelief (Mk. 8:12). Jesus came to Israel as the Good Shepherd, the one sent to gather the lost sheep of Israel (Ezek. 34; Mt. 9:36; 10:6; 15:24; Jn. 10:1–18). When Jesus considered Jerusalem’s destruction, He did not rejoice, but wept (Lk. 19:41–44). Despite His rejection and the resultant judgment, Jesus is ready even now to come as Israel’s Messiah and restore them according to God’s promises (Zech. 12—14).

Jesus rebuked His generation for rebelling against God, breaking the law, and not believing in God’s Word—the very Word that proclaimed Him as Messiah. Did this make Jesus anti-Judaism? No. On the contrary, Jesus committed Himself fully to being submissive to God’s will and Word as the obedient Son, even to the point of dying on a cross (Phil. 2:1–11).

Jesus was thoroughly Jewish. He was of Jewish lineage; He lived in and embraced Jewish culture; and He lived according to the Scriptures. To portray Jesus as non-Jewish or anti-Judaism paints a false picture of “the King of the Jews.” Rather, Jesus was the one—the only one—who obeyed God completely from His heart. Jesus is the one who has been blessed with all the promises of the Abrahamic and Davidic Covenants, and so He blesses all those who have put their trust in Him, whether Jew or Gentile.

There is no question Luke gave the lineage of Mary. Otherwise he changed every name given in Matthew’s account. This is the first time I remember seeing this author’s name. I have to ask myself why he didn’t write more articles but the answer is fairly obvious to me