Tzedaka: It Is More Blessed to Give

A story is told of the rabbi of Nemirov. His followers, all Hasidim, stated emphatically that every night their rabbi went up to heaven. Another Jewish group, Mitnaggedim (opponents), ridiculed the Hasidim about this belief. One particular Mitnagged thought the idea so preposterous that one night he decided to hide under the bed of the rabbi to confirm firsthand the impossibility of such a thing. At about 2 a.m., the rabbi arose, put on his coat, and took an ax in his hand. The frightened but well-hidden doubter followed the rabbi into the forest. Keeping his distance, he watched as the rabbi began to chop down trees then cut the wood into logs suitable for burning. He marveled as he saw the rabbi deliver his secret offering to the widows and the infirm in the town. The next morning in synagogue, when the Hasidim spoke of their rabbi going to heaven, the former nonbeliever surprised his group of followers and said, “Yes—to heaven, if not even higher.”

This wonderful but little-known story eloquently captures the essence of the Jewish idea of charity or giving. Because there is no literal Hebrew word for charity, the word tzedaka (pronounced tse-DOCK-a), meaning righteousness, is used. Synonyms for tzedaka are justice, truth, and kindness, making clear the importance of the redeeming qualities of giving within Judaism.

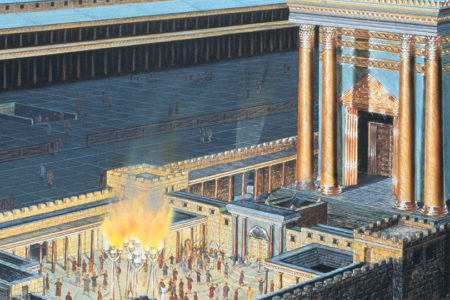

The Bible has much to say about giving. Numbers 7 alone devotes all of its 89 verses, almost 2,000 words, to giving. Contained in the Torah (the first five books of the Bible) are a variety of laws applying to the poor. Tithes for the poor (ma’aser ani), the gleaning of the field (leket), the year of release (shemittah), and the field corner to be reaped by the poor (peah) all relate to the Jewish idea of giving as justice. At the same time, compassion is also an integral part of giving. Deuteronomy 15:7–11 states that because there will always be poor people in the land of Israel, the Israelites were to stretch out their hands wide to those poor brethren around them and give without evil in their hearts. Proverbs 19:17 says that giving to the poor is like lending to the Lord.

Maimonides made a list of different kinds of contributions to charity. From the least kind of giving to the greatest kind of giving, his ranking reads:

8. He who doesn’t give enough and even that unwillingly, and in bad grace.

7. He who doesn’t give enough (according to his means) but what he does give he donates with good grace.

6. He who gives after he is asked.

5. He who gives before he is asked (both parties knowing each other).

4. He who “casts among the poor,” meaning that the recipient knows who gave, but the donor doesn’t know who received.

3. He who knows who is to get the money but sees to it that this person does not learn who gave it and thus avoids any embarrassment on his part.

2. He who gives charity without knowing who is to receive it and without the recipient being told who gave it.

1. He who helps someone save his business or get a job so that it will not become necessary for this person to become dependent on charity.

Other examples of the place charity holds in Jewish literature abound:

Charity equals all the other commandments.

A penny for the poor will obtain a view of the Shekinah.

Whom God loves He sends a golden opportunity for charity.

By benevolence man rises to a height where he meets God.

What you give to charity in health is gold, what you give in sickness is silver, and what you give after death is copper.

Other well-used statements on giving in Judaism are:

For your purposes it is more important to give often than to give much.

When you remember yourself, be sure to remember others.

One never asks questions when anyone wants food, even if they are complete strangers.

It seems evident that, biblically and talmudically, giving is an integral part of Jewish life. Therefore, it is not surprising that Jewish people are very generous. They are key players in the leadership of charitable organizations, especially those involving education (religious and secular), health care, and the arts. To what can we attribute this generosity? An old Yiddish proverb states, “The longest road in the world is the one that leads from your pocketbook.” Understanding the truth behind the humor in that adage, Judaism begins teaching about giving while its people are very young. As a child, I was taught various ways of giving, most of which centered around the synagogue. Funds for Israel, education, and immigration were usually raised by pledges. An old but effective way of developing habitual giving involved something called a pushke, which is a small collection box kept in the home. Various charitable groups will supply the pushke, have the family keep it for a period of time (usually a week), and pick it up before the Sabbath. Families collect money for any number of charities—trees for Israel, homes for senior citizens, widows, various brotherhoods, sponsoring passage to Israel for those who wish to migrate but cannot afford it, buying food for the hungry, etc.

We can learn much from observing our Jewish friends in the area of giving. Scripturally based, Judaism demonstrates that intertwined with its relationship to the Almighty is a compassionate and heartfelt eye on those of humble means. Our family has adopted the use of a pushke to collect money for various causes. We sit down together and talk about where we want to contribute this money.

Christianity, which was born from Judaism, differs, not in the importance of giving, but in the motivation to give. Nothing we do can make us righteous, but the Messiah’s followers will give and do so joyously because they have been given the greatest gift of all—salvation!