God’s Present Work in Israel in the Light of the Book of Esther

Over four thousand years ago God made a covenant with Abraham and his descendants, promising to be a God to them forever (Gen. 17:7). But now, in the present Church age, Abraham’s descendants have been set aside, removed from the place of special privilege and service which they once enjoyed. Exactly how, then, does God view Israel at the present time? Is He still God to His chosen people in a special way, even though as a nation they are largely unregenerate and wholly unable to function theocratically? Or has He written them off completely for the duration of the present age, choosing instead to work exclusively with the Church?

It will come as a surprise to some, no doubt, that much light is shed on this matter by the often misunderstood Old Testament Book of Esther. In fact, the very features of that book which have most frequently been misunderstood are themselves the keys which unlock its meaning and which thereby illuminate our understanding of God’s present relationship to His people and the work which He is doing among them at the present hour. The Book of Esther (Hadassah in Hebrew) plays an important role in Jewish tradition. The festival of Purim is based on this book. Does the book say something to them of which they may be unaware?

Two Misunderstood Features

One of the misunderstood features is quite well-known: Although a certain Persian king is mentioned 190 times in the 167 verses of the Book of Esther, God is not mentioned once. Further, although the book is full of crises and danger for Israel, there is no reference to Jerusalem, the Temple, the Law, the Covenant, sacrifices, prayer, love, or forgiveness. This lack of any reference whatsoever to God or His revealed theocratic institutions has led many Jewish and Christian thinkers to question the value, the canonicity, and even the historicity of the Book of Esther. The absence of the name of God and all religious activity is probably the reason it has not been found among the manuscripts retrieved at Qumran.

A second misunderstood feature of the book is its focus on the mere physical survival of Jews at the expense of their Gentile enemies. Christian interpreters, in particular, have been deeply troubled by the fact that Esther records the Jewish slaughter of 75,000 Gentiles scattered throughout the Persian empire (9:16). Some, in fact, have concluded that since such a wholesale massacre is inconsistent with “the Christian ethic,” the Book of Esther could not possibly be inspired by God and thus ought to be excluded from the biblical canon. Even Martin Luther is said to have confessed, “I am so great an enemy to the second book of the Maccabees, and to Esther, that I wish they had not come to us at all, for they have too many heathen unnaturalities.”

The widespread misunderstanding of these two features must not be permitted to continue unchecked. Neither the lack of any reference to God and to divinely instituted worship patterns nor the record of the destruction of 75,000 Gentiles marks the Book of Esther as inferior in some way to the other books of Scripture. Just as much as Deuteronomy, the Psalms, or Isaiah, it is inspired, inerrant, canonical, authoritative, historically accurate, and theologically significant. How, then, are these two features to be explained? And how do they serve to clarify the meaning of Esther and thereby reveal what God is doing in Israel today?

The Slaughter of the Gentiles

The objection to the murder of the Gentiles who hated and opposed the Jews is rooted in a failure to discern the distinction between God’s program for Israel and His program for the Church. Israel is not the Church, and thus her actions cannot be judged by the standards which God has established for the Church (see, for example, Rom. 11:14–26). Whenever distinctively Christian standards of conduct are superimposed on the Old Testament (or even on the Gospels), the inevitable result is misunderstanding and confusion. This is true when Christian standards are read back into theocratically normative accounts like Leviticus, Joshua, and Chronicles; it is even truer when the attempt is made to read them back into non-normative situations like those described in Judges, parts of Samuel and Kings, and especially Esther.

Actually, the failure to differentiate between God’s program for Israel and His program for the Church has led many to question, not only the propriety of the Jewish slaughter of 75,000 Gentiles, but also, at a more basic level, the validity of the very idea of an Israelite theocracy. Are we really to believe, they ask, that a loving God delivered millions of Hebrews from Egyptian bondage and then settled them in Canaan, when doing so involved the death of vast numbers of Egyptians and Canaanites? Doesn’t this contradict the New Testament teaching about the nature of God and how we are to treat our fellow human beings?

Those who pose such questions, however, understand neither the fundamental attributes of God nor the full implications of the fall of Adam. God is absolutely holy, and sinful men do not deserve to live on His earth at all. This, in fact, is the basic message of the Genesis flood. But God is also gracious, and, therefore, He determined to bless nations in proportion to their response to His message through the one nation, Israel, who herself was brought into existence by divine sovereign grace (Gen. 12:1–3; Dt. 7:6–11). Nations and individuals that hated Israel, however, thereby demonstrated their rejection of God’s gracious plan of salvation and were consigned to destruction.

Often the instrument which God used to accomplish the destruction was Israel herself. In such cases it was not only the baser, unregenerate members of the nation who were involved. Indeed, the most spiritual men in Israel—Abraham (Gen. 14:15), Moses (Num. 21:34–35; 31:13–18), Joshua Josh. 6:21; 10:28–40), Samuel (1 Sam. 15:32–33), David (1 Sam. 17:50–51; 27:8–11; 2 Sam. 1:1–16)—were frequently called upon by God to kill others for the furtherance of His purposes on earth.

For the Jews to have adopted the pacifistic attitude of live and let live toward idolatrous Gentiles in Palestine would have been to invite divine judgment (Jud. 1:19–2:23). In fact, such a tragedy is what finally happened. Because of centuries of disobedience to the theocratic program of their God, especially in religious compromise with Gentile neighbors, first the northern tribes (722 B.C.) and then Judah (586 B.C.) were deported and scattered throughout Mesopotamia and beyond. The outward forms of the theocracy were smashed by Gentile nations that hated the God of Israel.

When viewed in the light of God’s program for the Israelite theocracy, the death of 75,000 Jew-hating Gentiles during the reign of Xerxes cannot provide a valid objection to the inspiration and canonicity of the Book of Esther anymore than the death of the firstborn throughout Egypt constitutes an objection to the inspiration of the Book of Exodus. Actually, these inspired books show us that God took the Abrahamic Covenant seriously. In one case miraculously and in the other case providentially, God thwarted Satan’s desperate efforts to destroy His covenant people. Apart from the Exodus, Israel’s descendants would have been ultimately absorbed and paganized by idolatrous Egyptians. There could then have been no Messiah and thus no salvation for the world. But similarly, apart from the deliverance of Israel from the wicked plot of Haman, not only the Jews in Susa but also the theocratic community in Jerusalem would have been wiped out. And once again, there could then have been no Messiah and no salvation.

The Absence of God’s Name

In 536 B.C., only a half century before the opening scenes of the Book of Esther, 50,000 godly Jews returned to Jerusalem under the leadership of a governor named Zerubbabel and a high priest named Joshua. They joyously set up an altar of sacrifice and began to rebuild the Temple. Thus Jerusalem again became the center of God’s redemptive program for the entire world (Hag. 2:3–9; Zech. 4:1–14). Some godly Jews, to be sure, like Daniel, were physically unable to return with this expedition, and yet their hearts were with it (Ps. 137:4–6; Dan. 6:10). Many years later, there were a number of able-bodied young men who loved their God but were, nevertheless, still living in Babylon (Ezra 7:6–10) and Susa (Neh. 1:1–2:8). But the crucial and obvious point is that when the opportunity came, they fulfilled the desire of their hearts to return to Jerusalem in order to further God’s theocratic program.

The situation described in the Book of Esther, however, is vastly different. Unlike Zerubbabel, Joshua, Daniel, Ezra, and Nehemiah, Mordecai and Esther do not seem to have harbored any desire to relate to the heart of God’s theocratic program by journeying to Jerusalem, offering the prescribed Mosaic sacrifices on the altar through Levitical priests, and praying to Jehovah in His holy Temple. Nor does it seem that they were prevented in any way from going. It may certainly be asked, therefore, whether or not Mordecai and Esther really knew the God of Israel in a vital and personal way.

This question concerning the spiritual condition of Mordecai and Esther is a matter of no small consequence. Upon the proper answer to this question rest, to a large degree, both the explanation of the absence of God’s name in the book and our understanding of God’s work in Israel today. For these and other reasons, the question has been seriously debated through the centuries and deserves careful analysis.

That both the hero and the heroine of the book exhibited some elements of high moral character will be conceded by almost everyone. This is particularly evident in the crisis of Esther 4 when Mordecai, in his appeal to Esther to appear before the king on behalf of her people (4:13–14), made a veiled reference to the providence of God in light of the Abrahamic Covenant, and when Esther asked the Jews of Susa to fast for three days while she prepared to go to the king at the risk of her life (4:16).

Although all of this may be granted, our Lord’s analysis of the Jews of His day, who readily appealed to the Abrahamic Covenant (Mt. 3:9; Jn. 8:39) and who spent much of their time fasting (Mt. 6:16), should warn us that more positive evidences than these must be found to classify a particular Jew as belonging to the true “remnant” of Israel (Isa. 4:2–3; cf. Jn. 1:47; Rom. 9:6–8). Even in Israel today there are many Mordecais and Esthers who demonstrate great courage and nobility in their determination to die, if necessary, for the perpetuation of their nation and even of their religion. But very few of these courageous Israelis know the God of their fathers in the sense of trusting in His provision of eternal salvation through the merits of the Messiah (Rom. 11:25, 28; cf. Isa. 53:1–6).

In attempting to evaluate Esther’s spiritual condition, it must be recognized that she wanted to be a wife of Xerxes, a zealous Zoroastrian. Although the text does say that Esther was “taken” into the king’s palace and placed in the custody of Hegai (2:8), this does not imply that she was forced into the king’s harem against her will. The word “taken” has no negative connotations and in fact is used in verse 15 to describe what happened to Esther when she was adopted by Mordecai. It also must be recognized that Esther concealed her Jewish nationality for at least five years (cf. 2:16 with 3:7). This meant that for an extended period of time she had to disregard the dietary regulations set forth in the Law (2:9), and she had to follow idolatrous Persian worship patterns. It would seem, therefore, that Esther had little true regard for God, His Word, or His theocratic program.

A similar conclusion must be reached concerning Mordecai. It is unthinkable that a godly Jew would have concealed his identity for a long period of time and commanded another to do the same. Under the circumstances, this is clearly a breach of at least the intent of the first of the Ten Commandments. While some might suppose that Mordecai’s refusal to bow before Haman suggests the presence of deep-seated religious conviction, closer inspection reveals that such is not the case. First, it was not uncommon for Jews to fall down before political leaders (2 Sam. 14:4; 18:28; 1 Ki. 1:16). Second, Mordecai firmly insisted that Esther conceal her national identity and, in so doing, made it almost necessary for her to pay homage to the king. Third, Mordecai himself would have been expected to pay homage to the king when he later replaced Haman as the king’s favorite. It is more likely, therefore, that it was Mordecai’s pride, and not his religious convictions, which kept him from bowing before Haman. Thus the comments of J. Stafford Wright seem to be on target: Mordecai “may have been little more than a time-server. The Bible makes no moral judgment upon him, but expects us to use our Christian sense. He was raised up by God, but he was not necessarily a godly man.”

The reason, then, that God’s name and all theocratic ideas are obviously and meticulously avoided throughout the Book of Esther is clear. It is not because God’s presence in Susa was vague or uncertain. Nor is it because thousands of Gentiles died at the hands of Jews. The true reason is that Esther, Mordecai and the other Jews of Susa not only were outside of the promised land but, moreover, were not concerned about God, His Word, or His theocratic program centered in that land. Because these Jews had detached themselves from God and His revealed program, God refused to identify Himself officially and openly with their activities, their plans, or their plight.

God’s Work in Israel Today

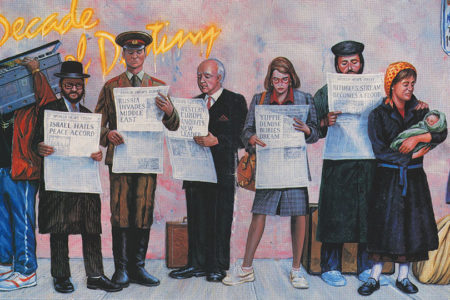

The complete absence of the name of God in the Book of Esther points to the spiritual tragedy of Israel today. Just like Mordecai Esther, and so many other Jews of the fifth century B.C., many modern Israelis are detached from God and His program. God has declared that salvation is to be found in His Son, Jesus of Nazareth, the promised Messiah (Acts 4:12), but most Jews have dismissed His testimony. As a nation, Israel has rejected her Messiah and thus is a spiritual enemy of the gospel (Rom. 11:28a). Therefore, just as in the days of Esther and Mordecai God refuses to identify Himself officially and openly with the Jewish state. In fact, He has broken unbelieving Israelites from their former place of privilege and service, even though they are the natural branches of the olive tree of His blessing (Rom. 11:17–22). This is the tragedy of Israel today.

But the Book of Esther is a message of hope for modern Israel as well. Although Mordecai Esther, and their contemporaries were uninterested in God and His theocratic program, and although God therefore refused to identify with them officially, these descendants of Abraham still enjoyed His protective hand. Instead of being eliminated by the satanic plot of Haman, they were providentially delivered, and, further, they were even enabled to put to death 75,000 of their enemies. Thus, God’s providential preservation of His people, even in their unbelief, is one of the major themes of the book.

Israel’s situation today is much the same. Even though she is unregenerate and cut off from her divinely given institutions because of unbelief, the nation has not been abandoned by her God. To this day, she is being providentially protected and enabled to defeat her enemies, for her God has not forgotten the covenant which He made with Abraham so many years ago.

This, then, is the message of the Book of Esther to our world today: divine rejection, and yet divine providence—tragedy, and yet hope. But Israel’s hope extends even beyond her present enjoyment of God’s providential protection. One day she will be restored to her former place of blessing because she is “beloved for the fathers’ sakes” (Rom. 11:28b) and because “the gifts and calling of God are without repentance” (Rom. 11:29). At that time she once again will be grafted into the olive tree from which she has so long been severed (Rom. 11:23–24), and, in fact, “all Israel shall be saved” (Rom. 11:26).

Little did Mordecai realize that Purim could not solve Israel’s real tragedy. For untold millions of Jews, his warning to Esther has found fulfillment: “thou and thy father’s house shall be destroyed” (4:14b). But he also spoke beyond his knowledge when he promised her, “then shall there relief and deliverance arise to the Jews from another place” (4:14a). That other “place” proved to be none other than Israel’s own Messiah, who spoke with infinitely greater authority and knowledge of Israel’s tragedy and hope: “how often would I have gathered thy children together … and ye would not. Behold, your house is left unto you desolate. For I say unto you, Ye shall not see me henceforth, till ye shall say, Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord” (Mt. 23:37–39).