Meet Hilda Goldberg

Editor’s Note: Hilda Salaman Ferder Goldberg, 83, spoke with Elliot Jager in her living room about growing up in British Mandate Palestine. These are her words.

My father was assigned to be the American Express bureau chief in Palestine, and my parents arrived from England in 1929—just in time for the Arab riots.

Mummy told me that in those days she kept a pot of boiling oil on the stovetop. She’d been advised to pour the oil down on any mob that tried to storm the building.

The American Express offices were situated just inside the Jaffa Gate of the Old City. My father always carried a gun and kept another in his desk drawer.

He had Jewish and Arab employees.

The bookkeeper was a man named Aaron Bloch. He went on to marry a girl named Dora. When she was already a grandmother, she was murdered by Idi Amin’s soldiers in Uganda in retaliation for Israel’s Entebbe rescue on July 4, 1976.

My parents lived on King George Street, not far from where the Great Synagogue now stands.

It was me, my parents, and my brothers and sister.

I was born in 1931 in Palestine at Shaare Zedek Hospital, which was then on Jaffa Road.

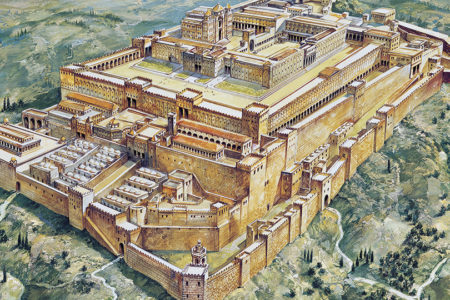

I attended an English-language girls school—Evelina De Rothschild. In many ways it was a typical British girls’ school. We wore uniforms and hats. And we also had Jewish religious studies. My parents sent me there because the language of instruction was English, and they could speak to the teachers and principal in English. The school was then in Musrara near the Old City.

It was the first school for girls in Jerusalem and was paid for by the British Jewish banker Lionel Nathan de Rothschild. A few years ago, when I moved back to Israel, we had a school reunion party, and many of the “old girls” turned out.

Outside of class, we spoke to one another in Hebrew; but inside, only in English.

The school had a rule: Because of Arab-Jewish tensions, the girls could not participate in extracurricular activities outside the school compound.

It was an exciting time. As my father was the head of American Express, he mixed with the business and political elite of Jerusalem, including [first high commissioner for Palestine] Sir Herbert Samuel.

Even we children enjoyed visits to Government House, on the Hill of Evil Counsel.

There was a store frequented by expats [ex-patriots] called Spinneys near the Russian Compound. I remember what a treat it was to go there. My parents would buy kippers [smoked fish] that had been delivered from London.

Every Friday, my mother made steak and kidney pie—kosher, of course!

There were three movie houses in Jerusalem: the Edison, Eden, and Zion. As a special treat, in 1938 I think, my mother took me out of school and we went to see Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs—in Technicolor—which had arrived in Palestine.

Every day an Arab milkman delivered our order on a donkey.

There were not many cars in Jerusalem, but Daddy had a Dodge and an Arab driver. When Daddy went through the Arab areas, the driver wore a ṭarbūsh [Turkish hat] and otherwise no hat at all.

Because of his [Daddy’s] position, we also had a telephone. I remember the number to this day: 5360.

Water shortages affected everyone. My mother had to recycle bath water to wash the floors. We had electricity, though there were often outages.

Then, in 1948, Daddy was reassigned to Cairo. We remained there until 1950 when it became too dangerous, and we moved back to England.