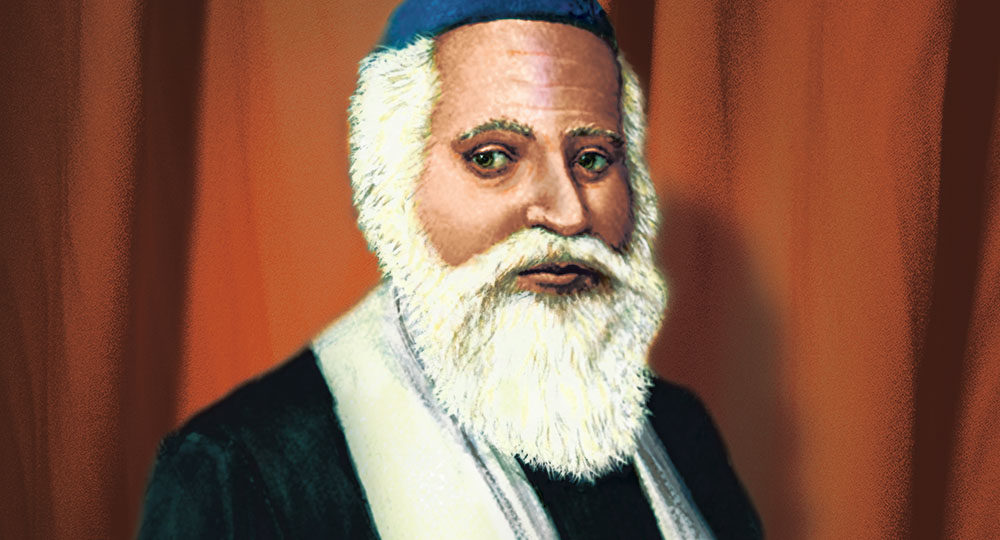

The Vilna Gaon: A Mystical Genius

As the 18th century dawned, European Jews were trying to recover from decades of destruction and disillusionment. In 1648 a Ukrainian named Bodgan Chmielnicki led a revolt against Poland. In the ensuing violence, Chmielnicki’s forces slaughtered upwards of 100,000 Jewish people and destroyed 300 Jewish villages. Hundreds were left homeless and wandered about as refugees. Out of the ashes, however, came a ray of hope, a 38-year-old Jewish man named Shabbtai Zvi.

In 1665 Zvi proclaimed himself the messiah. All of Europe and the Middle East buzzed with excitement. Zvi had the largest messianic following in Jewish history since the days of Bar Kokhba, the false messiah of the second century. But hope died quickly after Zvi converted to Islam a year later. The bad news spread rapidly, leaving the Jewish population completely dispirited.

Further, the condition of Jewish education did not help. Many traditional rabbis offered little spiritual sustenance because they focused on the art of pilpul, a method of exposition and debate that tries to solve religious controversies through crafty interpretations of talmudic minutiae.

Within this milieu, on April 23, 1720, in Vilna, Lithuania, a soon-to-be spiritual giant within the Jewish community was born. His name was Elijah ben (son of) Solomon Zalman. He became known as the Vilna Gaon (pronounced Gah-OHN, meaning “genius”), or simply HaGra (Hebraic acronym for “the Gaon Rabbi Elijah”).

The Vilna Gaon is such a revered figure in Jewish history that a body of legendary tales and epic deeds has grown up around him. Today it is difficult to discern what is fact and what is fiction.

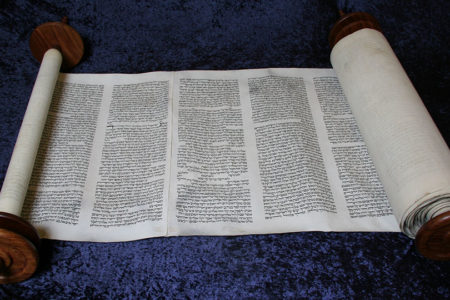

We do know he was brilliant, apparently even a child prodigy, perhaps with a photographic memory. It was said that by age seven he had learned Hebrew, the Old Testament, and the Talmud well enough to deliver a talmudic homily. By age 13 he had also sufficiently mastered the primary works of the Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism). His mind must have been astounding, for stories abound of his ability to recall almost any sacred passage and even state the word that ended the previous one. He earned the reputation of being a diligent student of all the recognized, authoritative Jewish writings (collectively called Torah). He either isolated himself in the woods or hibernated in his room, always keeping the shutters closed to prevent distractions from his Torah studies. He slept only two hours a night, and then only 30 minutes at a time.

The Vilna Gaon also studied secular subjects, such as history, mathematics, and astronomy, but only to enhance his understanding of Torah. The same was true of studying Jewish mysticism. He believed the Kabbalah, known as the “hidden Torah,” only benefited someone grounded in the “revealed Torah,” meaning the biblical and talmudic writings. The Gaon denounced the study of speculative philosophy, thus opposing much of what the famous medieval rabbi, Moses ben Maimon (Maimonides, also called the Rambam [1135–1204]), had used as the basis for his teachings.

The Gaon did find time to marry. Around the age of 20 he wed a young woman named Hannah. During their 40 years of marriage they were blessed with seven children, whom Hannah raised almost exclusively because the Gaon spent the majority of his time studying.

In the early days of his marriage, the Gaon left his young wife and wandered throughout Europe for a number of years. It is not known why he did so. Some speculate that he believed it would enhance his study of Torah. At 28 he returned to his family and settled down to a life of study, prayer, and contemplation, supported by a small weekly stipend that his great-great-grandfather had set aside for Torah scholars.

Despite his reputation for Torah insights, the Vilna Gaon never accepted any public position of importance. He was content to instruct privately a small band of disciples who later disseminated his thoughts and teachings. The Gaon is known for at least 70 works, ranging from Old Testament commentaries to explanations of the Talmud. Almost half of his teachings dealt with the Kabbalah alone. His interpretations became so highly regarded that he is included among the great codifiers of Jewish law.

Sometime during his midlife the Vilna Gaon decided to immigrate to the Holy Land. He left his family behind with the intent of bringing them later. For some unknown reason, the Gaon did not complete his immigration and returned to Vilna. He never explained other than to say, “I did not have permission from Heaven.”1 The Gaon never made it to the Holy Land, but some of his followers did, promoting his teachings there.

The Battle With Hasidism

Toward the latter part of his life, the Vilna Gaon enmeshed himself in battles not confined to the study hall. He was imprisoned at least twice for helping to kidnap a Jewish boy for the purpose of bringing him back to Judaism after the boy converted to Catholicism. The Gaon’s most important battle, however, was with some of his own Jewish brethren.

Hasidism, led by its founder, Israel ben Eliezer (also called the Ba’al Shem Tov, “master of the good name” [1700–1760]), began in southeast Poland and quickly made its way into Lithuania, including Vilna. Traditional rabbis, such as the Vilna Gaon, saw the new movement as a threat to everything they held dear. They believed Hasidism would split the Jewish community. They feared its emphasis on faith and emotion over objective Torah study, and they decried the unveiling of Kabbalah secrets to the unlearned. Most of all, they viewed Hasidism as a break with tradition, thus diminishing the authority of Torah scholars and their legal rulings. As a result, the Vilna Gaon eagerly signed two official bans of the Hasidim, one in 1772 and the other in 1781. To traditionalists, the Vilna Gaon stemmed the tide of Hasidism’s extreme elements, while defending traditional Judaism and scholarship.

On the third day of the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot) in 1797, the Vilna Gaon died. His funeral drew hundreds. For many years Jewish pilgrims visited the Gaon’s gravesite, believing the act brought merit and blessing to their lives.

His Rights and Wrongs

As with any person, the Vilna Gaon’s life was multifaceted, punctuated by both strengths and weaknesses. For example, the Gaon rightly emphasized the importance of prayer, believing proper intent of the heart is what mattered. He also correctly concluded that the answer to man’s spiritual needs is found within God’s Word, and he taught that the key to memorization is right affections: “The way to overcome a poor memory is to learn with love and fear of Heaven….That which is precious to someone remains in his memory.”2

The Gaon believed the way to overcome an evil tongue is to praise others, and the way to trust God and conquer fleshly desires is to learn to be content with what you have.

Where the Gaon excelled, of course, was in the realm of Torah scholarship. He wanted to demonstrate the absolute unity between the written and the so-called oral Torahs, proving they are but one, divinely given work.

As remarkable as he was, however, he also erred. He was wrong to give the same authority to extrabiblical writings that he gave to the Bible. There is only one Torah; it does not include the Talmud, the kabbalistic writings, or any other noncanonical texts. Only the 66 books of the Old and New Testaments are the revealed Word of God.

The Vilna Gaon also erred in his principles of interpretation. As do many rabbis, the Gaon believed that each text of Scripture, even every letter, has four levels of meaning: (1) plain or literal, (2) hints or allegorical, (3) homiletical, and (4) secret or mystical. Biblical passages often become twisted or misunderstood as a result of this type of hermeneutic. Instead, the general rule should be the following: Unless figurative language is clearly intended, seek no other sense but the plain sense, otherwise you may end up with nonsense.

The Gaon’s endorsement of Kabbalah is perhaps his most glaring error. He strongly believed in the authority of the Jewish mystical writings and taught that one could not fully grasp the plain text of the Torah without studying the Kabbalah. He also believed that learning the Kabbalah was, in fact, necessary to bring the Messiah.

The Gaon’s mystical convictions included “practical Kabbalah,” the use of amulets and incantations containing the names of God or angels. Once, when a convert to Judaism was imprisoned, the Gaon offered to free him by using his powers of practical Kabbalah. The Gaon’s participation in Jewish mysticism also involved communion with spirits. The Gaon claimed to have had secrets revealed to him by the patriarch Jacob, Moses, the prophet Elijah, and dead kabbalistic rabbis. He even admitted that, before he was 13, he tried to create a golem (a soulless creature made of clay, brought to life by kabbalistic rituals). This acceptance of mysticism, with its accompanying distortions of Scripture and connection with deceiving spirits, mars the Gaon’s otherwise admirable reputation.

Most cultural heroes are bigger than life. The Vilna Gaon is no exception. Because of his knowledge of Torah and his piety, he is said to have possessed supernatural powers. His blessings on people supposedly came true. He purportedly healed the blind, predicted the future, and protected his community from ravaging mobs. It is said he even kept a cannonball from exploding.

In truth, these incredulous events are unnecessary for Jewish people to appreciate the legacy of the Vilna Gaon. In their eyes, he was a model of diligence, scholarship, and devotion. In almost every Jewish community, his impact is still felt today.

ENDNOTES

- Betzalel Landau, The Vilna Gaon: The Life and Teachings of Rabbi Eliyahu the Gaon of Vilna (Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, Ltd., 1994), 161.

- Ibid., 54.

In the 21th century, we can see many people looking for answers to their spiritual life. It’s like people in our world are connecting to the worship of Angels and other religions like mixing the Buddha teachings with Jewish practices. I stand by the 66 chapters of the Torah and the beliefs of One Universe Creator and the coming of the Messiah and building of the Temple in the Old City of Jerusalem. What is your opinion?

Based on what do you say that “The Gaon’s endorsement of Kabbalah is perhaps his most glaring error”? Such a genius who was also a master of every scientific field, it seems rather flippant to dismiss his mysticism as erroneous.

Thank you, Alexander, for reading my article and for your question. It was not my intent to come across as flippant regarding the Gaon’s endorsement of Kabbalah. I gave it much thought when I wrote these words, “He was wrong to give the same authority to extrabiblical writings that he gave to the Bible.” With all due respect for the Gaon’s knowledge and expertise, I would say the same of anyone who seeks ultimate truth from mysticism, whether Kabbalah or any other form of mysticism. Ultimate, final, objective truth is only found in the written, inspired text of the Bible. Being learned and educated in other fields is all well and good. But in order to acquire an eternal, personal relationship with the God who created us, one must know and study the Bible – His word. Nothing else is needed. Again, thank you for your inquiry.

I found your article very interesting. I have some additional information on Vilna Gaon that you will find most interesting. Please send me your email and I will send it to you.

God Bless, Luke